Sex permeates French society, all the way down to the language. French nouns have genders, either masculine or feminine. It’s possible to figure out the gender of a word because of certain “rules” (words ending in -ion are often feminine) but of course there are exceptions and if you don’t know the rules you have to guess. If you don’t know these “rules,” you can take a guess, but a word’s gender can be counterintuitive. For example, chemisier (blouse) is masculine while chemise (dress shirt) is feminine. Go figure.

Some nouns can change gender depending on the person they describe. A male director is un directeur and a female is une directrice, while a male baker is un boulanger and a female une boulangère. But some professions have been linguistic holdouts and are always masculine: a professor is un professeur and never une professeure, even if she’s a woman.

This has finally changed. After years of resistance, the esteemed Académie française has just announced at the beginning of March that the names of all professions may be “feminized.” Now a writer can be un ecrivain or une ecrivaine, the head of a company or the person cooking can be un chef or une cheffe, and an author can be un auteur, une auteure or even (let’s go crazy here) une autrice.

By Francophone standards, France has been behind the times on the matter. Other French-speaking countries like Belgium and Switzerland joined the linguistic modern world decades ago; Quebec recognized “feminized” professional names back in 1979. What took the French so long?

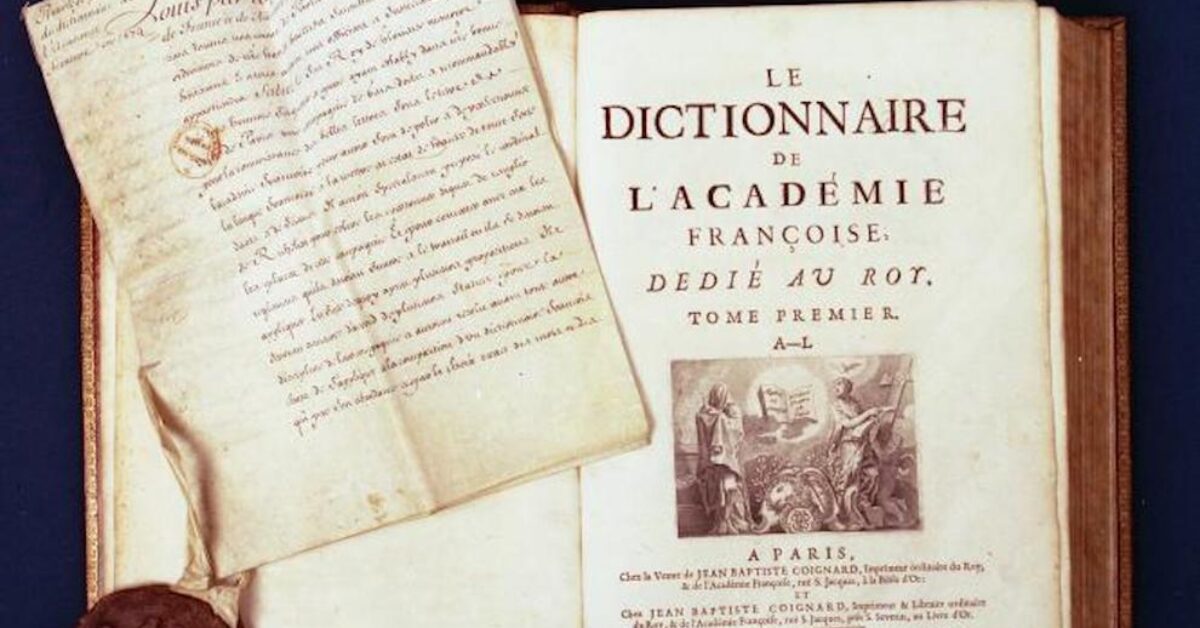

For this, we can point a finger at Académie française. This august body was created way back in 1635 to be the protector of and authority on the French language. To this day, while in session its members wear elaborate green uniforms and carry swords, and if there’s a question about language, big or small, it’s the Académie that has the last word. And it moves very, very slowly.

It wouldn’t be wrong to say that the Académie has a legacy of being behind the times on its acceptance of women. You would think that it should take less than 350 years for the Académie to welcome its first female member, and you would be right… but just barely. It was only in 1980 (after 345 years!) that the Académie finally invited the brilliant writer Marguerite Yourcenar to join, and to date only nine women have ever been members. Even today, its ranks include 31 men and only five women.

The Académie moves just as slowly when it comes to changes in the French language. In 1997, its president opined that terms like ecrivaine and cheffe had “little chance” of ever moving into the linguistic mainstream. Even as late as 2014, when such terms had become common, the Académie vehemently stated that they constituted “true barbarism.”

It’s worth noting that the Académie has no sanctioned power in the way that the government does; the only authority it has is what is conferred upon it. And as hard as it has fought to keep English out of French, going as far as to have a webpage dedicated to French words you should use instead of English words (un courriel instead of un email), the citizens of France have paid no heed, instead incorporating more English into the daily lexicon. The Académie’s influence extends truly only to the language and grammar used in legal and government documents. But that hasn’t stopped — and won’t stop — them from trying.

Times change and eventually the Académie does, too. But let’s not expect too many changes to the French language any time soon. We can be sure to count on masculine blouses and feminine shirts for many years to come.