The French may tease Americans about nasally accents and the way we casually throw language around, but listen to them speak and hear the truth: the French love using English words. Un brunch. Un brainstorming. Chiller (meaning, “to chill”). They integrate English into their daily, business, and internet language.

Unfortunately for French fanatics of English, Académie Française, the self-proclaimed authority on French language, is on a mission to stamp out English from French. A whole section of their website is dedicated to the French words that should replace the English words French people actually use in daily conversation (e.g., instead of “hashtag,” use “mot-dièse,” literally meaning “hash-word”).

Académie Française’s opposition to English language is wrapped up in France’s commitment to its nationhood. France is a very old country with deeply rooted cultural traditions and committed to its language and its values. “Language is a proxy battle for the protection of French culture,” explains Dr. Damien Hall, a professor of linguistics at Newcastle University. “The French see the incursion of English terms as an invasion into their language.”

The bad news for traditionalists is that the invasion of English can’t be fought off because it’s not an invasion: the French have been choosing to bring English into their language for centuries.

Frenchifying words

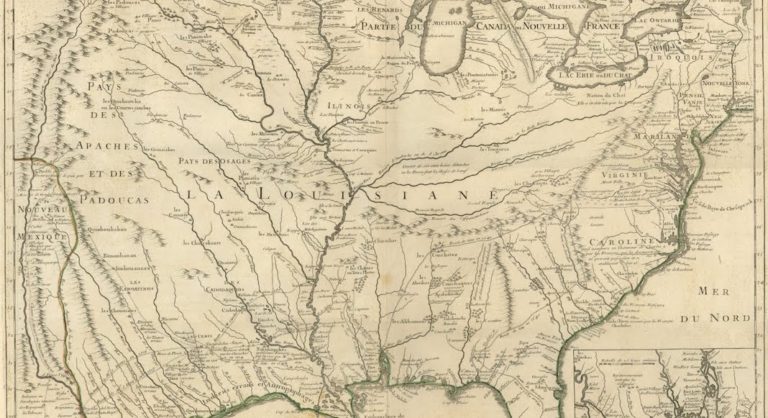

As Dr. Hall explains, “There is more English in French at a more fundamental level than a lot of people think, because the French have been taking English words for centuries” from places where people speak English or from the historical ancestors of English. And “given the tendency for the French to think that French is really important to their sense of nationhood, anything that can be translated will be translated.” For example, the main points on a French compass — nord, sud, est, ouest — are borrowed from the sailors speaking Anglo-Saxon or Old English (c. 450 – c. 1066) that landed in northern France. Or consider words that end in –ité, like faisabilité: it’s made up of Latin elements, so it could have come from Latin. And yet, says Dr. Hall, “the French didn’t make that up themselves, they borrowed the word ‘feasibility’ from English and made it look like French.” In Dr. Hall’s Le Petit Robert dictionary, “faisibilité” is first cited in the 20th century, yet in the Oxford English dictionary, “feasibility” is a 19th-century word.

Even in recent years the French having been taking English words and Frenchifying them or even giving them new meaning: “un parking” (a parking garage), “un brushing” (a blow-dry), and “babyfoot” (foosball). So why are Frenchified words falling in out of favor and being replaced by untranslated English terms? Love of trends and love of business.

Trend over tradition

People – including the French – like trendy things, and English is what’s trendy. For example, on a 17th-century map Dr. Hall viewed that was drawn by a French colonizer, New York is labelled, “Nouvelle York.” It made sense to translate New York’s name because, at the beginning of its existence, it was new, obscure, and referred to within a French context. But then, at some point not too much later, New York became a fashionable place and subsequently so did New York. “It became easier for people to know what you were talking about if you just used the original name.” The trendiness of English has brought words like le brunch, le wellness, le roof top, and more into the French lexicon.

The exception to trend over tradition are words that already look French-ish. For example, California has an -ia ending that became an -ie ending (i.e., Californie). Despite California becoming trendy for the French in recent years, it has remained Californie because the English word “California” looks French enough that it’s not worth the effort and confusion of translating it back into English. (For an example of a situation where this wouldn’t work, consider how different Nouvelle-York is from New York, which doesn’t look like a French word at all.)

English: the language of business

Hypothetically, English could stop being trendy, but the language would still be deeply engrained in French because of business. “Business is what’s trendy,” states Dr. Hall. “Between the United States and Britain and the other English-speaking countries in the world, that’s the vast majority of business in the world.” Words like un meeting, FYI, marketing, and hundreds more have entered the French’s lexicon via business, and French president Emmanuel Macron’s push for “startup nation” will only bring more.

The fight France now finds itself in is over its identity: “They want things to be in French, but they also want things to be fashionable,” says Dr. Hall. Unfortunately for the French, “in France, these are two trends that go in the opposite direction from each other.”

There is one place that won’t have to decide anything about its identity because it doesn’t care about being fashionable: the bureaucracy. “The Academy has quite a bit of power when language is quite formal. People who are writing very formal language and legal language and so on are more likely to take notice of what they say,” notes Dr. Hall. Ads, for example, are required by law to be written in French. However, they cannot legislate what language the French may or may not use on their own time. And judging from the historical precedent and still-growing presence of English in France, Académie Française is going to be fighting an impossible battle. “They’re not going to be able to stop people doing this,” Dr. Hall smiles apologetically. “I do think that it is hopeless.”