“Chanson is not a musical genre so much as an ideological narrative,” explains David Looseley in his 2012 book, Imagining the popular in contemporary French culture. The chanson he refers to is la chanson française, a genre of music so intertwined with French culture that it literally translates to “French songs.”

But the name is hardly an exaggeration. The chanson style traces its roots back to the troubadours and French lyric poets of the 12th and 13th centuries, namely François Villon, back when lyric poems were often set to different popular tunes at will, and considered their own unique form of folk art. One of the first transformations of the genre came in the 1840s, when post-Revolution Romanticism led to a glamorization of rural living and folk traditions, and the government began putting in effort to collect and anthologize traditional songs. Looseley proposes that musicians of the late 19th century “sought to pickle a mythical popular-musical past,” with songs, “characterised by wit, satire and Epicureanism.” Children began learning these folk songs in school, versions sanitized to remove regional dialects in an attempt to “fabricate a national popular taste.”

This is where chanson becomes synonymous with French national identity, and, moreover, a “national memory,” a shared culture that evokes the land, using the language—the French language, as determined by the government, scrubbed of all local variety, and meant to be sung in a specific accent accepted as “standard.”

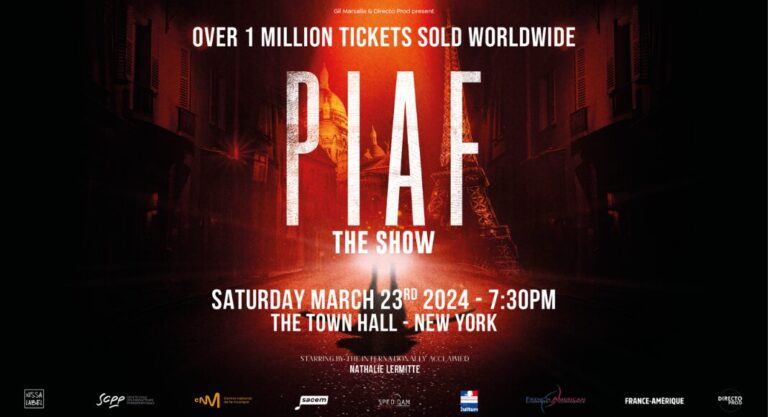

Chanson faced its first great threat with the music halls of the late-19th century, which favored dance music, spurred on by Anglo-Saxon influence. Black American musicians between the two World Wars led a jazz craze in France that championed movement over contemplative listening. Chanson then returned to prominence in the 1930s, with Édith Piaf and Charles Trenet leading the movement. “The pleasure that Piaf engendered in the 1930s was nostalgic and commemorative, for her work reacted to cosmopolitan modernity by largely pretending it was not there,” writes Looseley. Thus, by the 1930s, chanson was already nostalgic for the 1840s, when it had been nostalgic for the 1400s. “This Proustian reminiscence of a national past, helps explain the pleasure of Piaf even today.” While American music might be always focused on an individualistic ideal, moving towards the next new thing, French music tends to turn back on itself, not out of lack of ingenuity, but for an appreciation of a national identity based on community over self, heritage over innovation.

By the 1950s, cramped cabarets in Paris gave preference to solo singer-songwriters who could accompany themselves, thus building out the idea of the French singer-songwriter, known as an ACI (auteur-compositeur-interprète). Singers like Jacques Brel and Charles Aznavour epitomized this archetype of the singular performer whose songs were self-penned instead of being cranked out by the Tin Pan Alley hitmakers of the previous decades. It continued the chanson tradition of songs that were focused on lyrics and vocals, creating an intimacy with the audience both sonically and in terms of content.

In the 1950s and 60s, when rock’n’roll was dominating the U.S. and U.K., music industry execs in France rushed to produce their own version of the cash cow Elvis Prestley, a native Frenchman by the name of Johnny Hallyday. But French rock was always dismissed as a cheap imitation, and chanson française artists continued to dominate the airwaves. And in the 1970s, la nouvelle chanson française came to light, the product of musicians raised on both French classics and American pop and rock.

Even rap was not impervious to the assimilating forces of chanson, with work by rappers like MC Solaar in the 1990s quickly entering the ideological canon of la chanson française due to their focus on lyrics. The controversial 1994 radio quotas in France actually benefited rap by cutting out competition from American pop, and freeing up space for homegrown talent.

The latest iteration of la chanson française, however, is particularly suited to the moment: sad girl pop. While global phenomena like Billie Eilish and Olivia Rodrigo have popularized intimate, vocally forward pop songs with minimal instrumentation, a similar style has emerged separately and organically in France. The Spotify bio of French pop singer Hoshi refers to her as the “nouvelle étoile de la chanson française,” while Yseult’s calls her “le nouveau phénomène de la chanson française.” Other artists like Aloïse Sauvage, Pomme, and Clara Luciani all fall somewhere in the chanson category, while megastars like Angèle and Zaz mix chanson with rap, jazz, or electronic music to create something original yet definitively referential.

It’s evident when listening to these songs that they aren’t made in response to current American pop trends… there’s a nostalgic quality to them, a certain Frenchness it can be hard to define. (Even their literal Frenchness, the fact of being sung in French, is not to be taken for granted, considering the number of French musicians who sing in English in order to cater to global demand.) Yet they are of the moment, moody and minimalistic, putting storytelling and voice front and center, inviting you in so close that you almost feel as if you’re intruding upon a private moment. This is the magic of la chanson française: it plods along quietly, wrapping itself in layers of cultural memory, so that when it reappears it feels already familiar, a safe place to call home.