Music is an art form defined by its ability to be shared, borrowed, or stolen. As a cultural powerhouse, trends set in the United States tend to find their way across the Atlantic to Europe, where they are adopted and adapted as seen fit. But the large bulk of American popular music has similarly been taken or appropriated from Black Americans: Jazz, blues, rock ‘n’ roll, hip-hop, you name it.

This article focuses on the two Black American musical genres—jazz and hip-hop—that fiercely took hold in France during the twentieth century, and how they have, over time, reflected France’s own relationship to race and immigration.

“Introduced to France by African-American Soldiers during World War I, the emerging popular musical genre called jazz captivated the French public,” explains William A. Shack in his book, Harlem in Montmartre: A Paris Jazz Story Between the Great Wars. Bandleader James Reese Europe recruited Black Harlem’s musicians for New York’s 15th Heavy Foot Infantry Regiment, also known as the Harlem Hellfighters, to play in military bands during World War I. The all-Black detachment set foot in France in 1918, where Europe’s reputation preceded him. “General John Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, immediately ordered the band transferred to his headquarters, so it could entertain the officers from the British and French armies who were called to conferences with the general.” Thus, “the Hellfighters were Pershing’s personal band for over a year,” despite the fact that any ‘fraternization’ between white and black soldiers was expressly forbidden. The Hellfighters later went on a 12-city tour throughout provincial France, where citywide crowds would gather to hear them play.

Discovering America

Rather than return home after the war, many of these musicians (like Mitchell’s Jazz Kings, led by drummer Louis Mitchell, one of the first successful Black jazz musicians in Paris), settled in Montmartre. “Hot Clubs” emerged, spreading across Europe and inviting the great American jazz talents to come to France to play concerts and sell records. Beyond employment prospects, Black Americans enjoyed previously unknown freedoms in France, even sometimes experiencing “a strong pro-Negro prejudice,” as Parisians associated jazz with African-Americans.

“In 1919 the capital was poised for gaiety, and Parisians discovered America. French citizens of all ages looked to the horizons of the Atlantic for symbols of popular culture that fantasized a world divorced from the past.”

Although many aspects of French society seemed to like jazz, the racial and appropriative undertones cannot be overstated: “It appealed to the rather phony ‘populism’ of men like Jean Cocteau; its ‘primitive’ sound and ‘savage’ quality attracted the surrealists; and the musicians adopted it as a way of thumbing their noses at the ponderous pretensions of the Wagnerian school.” Black musicians were pigeonholed into the renowned “Harlem style,” as other forms of jazz remained on the margins of the French music scene. Regardless, Black musicians came to Paris in droves, as every nightclub in town sought their artistic voices. Black performers like Josephine Baker and Bricktop became beloved public figures, as the French grew fascinated by both their ability to draw crowds as well as their ostentatious personal lives.

The 10% Law

It wasn’t long before white French bands decided that they wanted to do what these Black Americans were doing. Musicians like Paul Whiteman, the self-styled “King of Jazz,” was one such proposed challenger, whose big band concerts acted as sanitized mimicry of ragtime jazz, more appropriate for the concert hall than the hole-in-the-wall jazz club. But, Shack notes, “Whiteman’s concert came at a time of lively debate in Parisian intellectual circles among writers, music critics, and classical musicians on the cultural and aesthetic merits of this new musical sound. Some critics characterized jazz as only noise and cacophony, and dancing to it the death of intelligence; others raised the question, is it music?”

These kinds of debates led to a rule known as the 10% law in France, which limited the number of foreign musicians employed by an establishment to 10 percent of the total number of French musicians employed there. This might sound familiar to anyone familiar with current French radio law, which mandates that at least 30% (previously 40%) of songs played must be French-language. French musicians were so disturbed by the popularity of Black American artists that they characterized both the influx of Black immigrants as well as the move towards jazz and traditionally Black music as the “Black Peril.” In an effort to resist this racist rhetoric, “a salon of French musicians was formed to popularize the works of French composers.”

But the 10% law didn’t benefit French musicians. The public had developed a certain taste, and when it was taken off the menu, they stopped coming to clubs to hear music, plunging Paris into a musical depression. By the time the Nazis invaded, France’s great jazz era was already at its end, the final straw being the persecution and systematic eradication of this “Negro-Jew” music during the Nazi occupation and Vichy regime.

Bambaataa in the Banlieues

In a sense, however, World War II had a lot to do with the birth of France’s next great musical love affair: hip-hop. During France’s post-war restoration, an enormous influx of immigrants from France’s colonies arrived to help rebuild the country, in return for citizenship. In the 1980s and 1990s, the children of these immigrants, many of whom were raised in France’s banlieues, began borrowing inspiration from Black American rappers and hip-hop artists at the movement’s forefront.

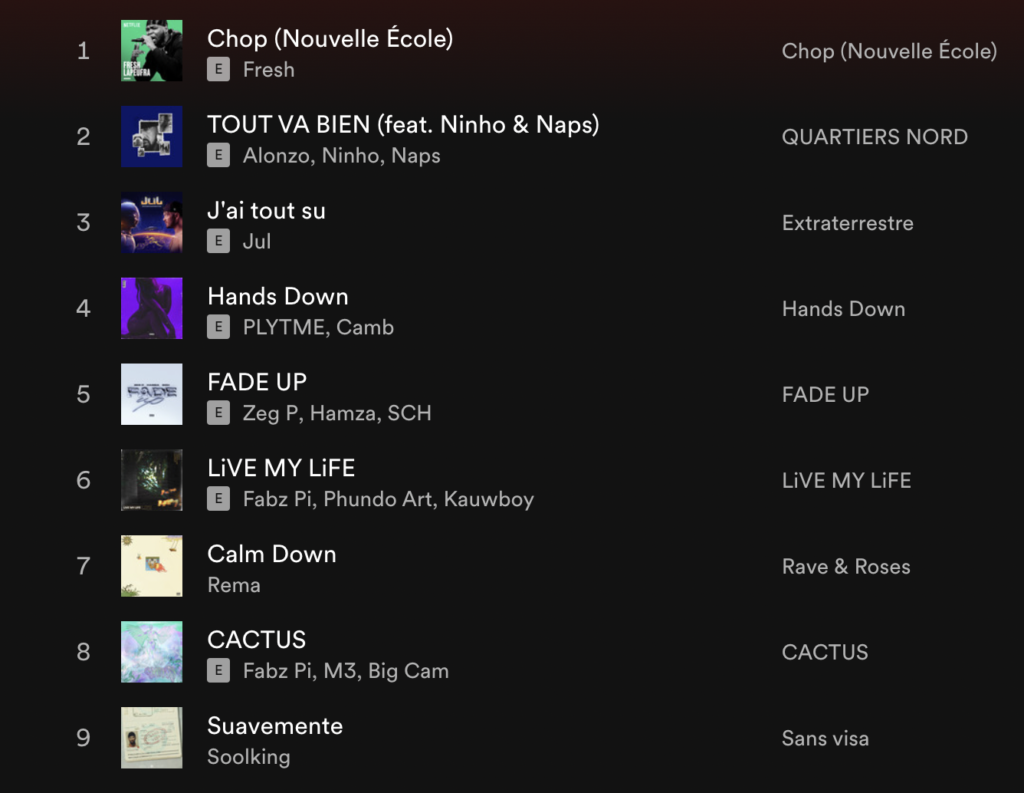

France now has one of the largest hip-hop scenes outside of the United States, and though the genre has bled into pop in most of the world, its popularity in France is striking. On Spotify’s Top 50 tracks currently in France as of June 27th, 2022, 32 tracks are songs by Francophone rappers, like French-Congolese rapper Nihno, and Alonzo a Marseillais of Comorian heritage who is a leading voice in both French rap and Afrobeats.

In “The Evolution of French Rap Music and Hip Hop Culture in the 1980s and 1990s,” André J.M. Prévos explains how this came about. It starts with Afrika Bambaataa, the South Bronx DJ and rapper, establishing the French branch of the Zulu Nation, a gang centered on raising Hip-Hop awareness, in the Parisian banlieues. This connection is an interesting one, as the Zulu Nation promoted ideals of Afrocentrism, a concept embraced by some Black Americans despite their being generations removed from the African continent, to the French banlieusards, many of whom were immigrants or children of recent immigrants from a range of West and North African countries, like Senegal and the Ivory Coast or Morocco and Tunisia.

These young French men took quickly to the genre, with MC Solaar’s 1991 disc, Qui sème le vent récolte le tempo, and the 1989 rap anthology Rapattitudes (featuring artists like Suprême NTM, Pouppa Claudio & Ragga, and Puppa Leslie) setting the standard. Many of them studied rap in the United States, in the New York or LA hip-hop scenes, and imitated American rappers in their style and content. “Claims of ‘authenticity’ on the part of other performers also reminded listeners that the artists saw themselves as part of a tradition adopted in its entirety without dilution or ‘whitewashing,’” explains Prévos. “What they see as their central mission is a continuation of rap as a vehicle to popularize and vent the anger and the frustrations of many disadvantaged or sometimes mistreated individuals, and to defend the cause of the poorest and least socially-integrated segments of French society.”

Reimagining colonial roots

French rap quickly became its own genre, however, with content focused more on social justice and activism than the gun violence and drug culture prevalent in American “gangsta” rap. It also tackled the issue of the preeminent issue of French colonialism. In the essay, “French Rap Music Going Global: IAM, They Were, We Are” by Seth Whidden, the rap group IAM’s music is used to illustrate the relationships between many of these communities and their own colonial history. IAM takes after the “Pharaoh” style of French rap, mainly based out of the Mediterranean city of Marseille, which uses the imagery and history of Egypt, one of the world’s oldest and grandest civilizations, as a backdrop against which to contextualize the disenfranchisement of young Arabs in France; “[IAM’s] insistence on Egypt affords them the opportunity to claim an African heritage without being immediately pigeon-holed into the role of the colonized and oppressed people speaking out against the French imperial power that is so often seen in Francophone discourse.”

These children of France’s colonies, many of whom know what it’s like to be told to “go back where you came from,” are creating spaces for themselves and their communities, as they become some of the most influential figures in mainstream French culture. Although hip hop has reached the French mainstream, it’s important to remember this art as a historically Black form of expression that has come to reflect a spectrum of marginalized cultures and experiences.