When I was in the 9th grade, I sat through my éducation civique (civic education) class as we all prepped to hopefully pass the brevet, a much anticipated French middle school exam. Our histoire-géo (history-geography) teacher pressed the importance of using the correct rhetoric on our exams, emphasizing France’s republican tenets of universal freedom and equality—liberté, égalité, fraternité. These cultural understandings of equality and republicanism have influenced contemporary French culture, where discussions of race are often rejected in favor of colorblind language. One often hears the phrase, ‘one race the human race,” and many French politicians, including Président Emmanuel Macron, stand against the “racialization” of French society, arguing instead for “integration [and] universalism.”

I guess I was thinking about all of this because I recently watched Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris (1970), a somewhat forgotten documentary that follows James Baldwin through his life in the artistic 6ème arrondissement: his favorite small bars that inspired his classic novel Giovanni’s Room, colorful contemporary art galleries, and cafés in the Algerian quarter. James Baldwin moved to Paris in the 1940s, and spent much of his life between the U.S. and France; however, the reason the film reminded me of France’s mainstream colorblind rhetoric was the perspective from which the directors and interviewers approached the film.

Throughout the documentary, British and French interviewers carry a narrative of Baldwin finding liberty abroad; a Black man who escaped racism. The movie implies that racism is solely an American problem, and white people in Europe are removed from issues of racial and ethnic prejudice. However there are wrinkles in this utopian idea, as Baldwin himself states, “The Algerian in France is the nigger in America.” And, since Meeting the Man, France has seen an increase in West African and Arab immigration, which has only further revealed the myth of a colorblind Republic.

Unsurprisingly, as I watched the film, I most enjoyed the scenes of James Baldwin meeting with other Black artists in Paris. Sitting in small well-lit galleries, Baldwin and others seemed to speak freely, slipping into my father’s ’60s New York slang, snapping and saying “give it to ‘em” in call-and-response. In these scenes, Baldwin moves past the confines of condescending interview questions like: “in a literal sense, you are writing for white people. Are you aware of that […] more white people read your novels than Black people.” Instead, Baldwin echoes Franz Fanon with palpable enthusiasm, “What’s going to happen, sooner or later, all the wretched of the earth in one way or another next Tuesday or next Wednesday, will destroy the cobblestones on which London and Rome and Paris are built. The world will change because it has to change […] The party is over.” This idea of black men huddled in a room, seeking to unearth and repave the cobblestone roads of western ideology, as Baldwin also faced pretentious and prejudiced interviewers, was unbelievably striking to me.

It is true that Baldwin moved to Paris at twenty-four and found solace in the city. In France, Baldwin was perceived and celebrated as an erudite American writer, whereas in the U.S. he faced constant racial and sexual discrimination. Baldwin does not remain uncritical of France and western Europe as a whole; instead, in the film, we find him describing European racialization as distinct from the U.S., but not non-existent. When the interviewer asks Baldwin why he does not understand himself as having “escaped,” Baldwin states, “What have I escaped? Where, anyway, would I escape? To your country? […] Where does a fleeing Black man go?”

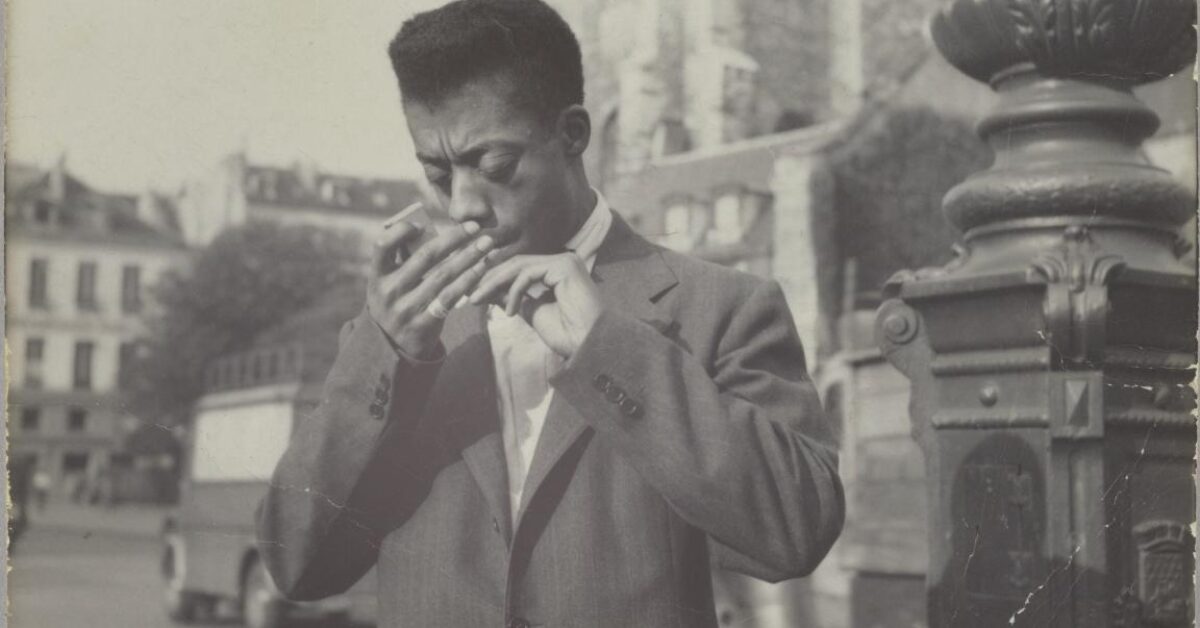

But then Baldwin shifts the tone by saying “…the logic of despair isn’t for me. A despairing man doesn’t write.” The documentary cuts to his fingers, holding a cigarette, as he walks along Les Invalides in a gray French trench coat.

For me, this was one of the most powerful moments in the film. Baldwin’s infectious and mirthful laugh and casual demeanor belie the serious import of his writings, activism and painful life experience. Indeed, in those small rooms amongst Black creatives or in the smokey gay bars of Paris, he allowed himself to live, not in despair but in resistance; as the film rolls into the credits, Baldwin states “If you live under the shadow of death, it gives you a certain freedom. I’m perfectly happy, odd as it sounds, and relatively free.”

Charlinda Banks is a rising Junior at Brown University studying International and Public Affairs & Literary Arts. She is currently an intern at Frenchly, and she is passionate about all things francophone and creative writing.