It has been a month since the Russian attacks began in Ukraine. On February 24th, Russian President Putin announced the beginning of a “military activity” in Eastern Ukraine. While in his own country Putin continues to call his army’s presence in Ukraine an “activity,” the reality is a full-fledged war now recognized by all nations except Belarus and Cuba. (China and India are taking neutral stances in their eagerness to better their relationships with Russia.)

The New York Times reports that over 3.5 million Ukrainian refugees have left the country. President Biden has vowed to accept 100,000 refugees in the United States and donate one billion dollars in humanitarian aid to the Ukrainian refugee crisis. While some people were able to leave, others are fleeing to western Ukraine to mountain homes and villages, like mine. I grew up until I was 8 in Ukraine, and my family still has a home in the Carpathian Mountains. We have opened the house to refugees escaping from cities that are being bombed. Yulianna Fitsay, my classmate and dentist, is currently facilitating that housing.

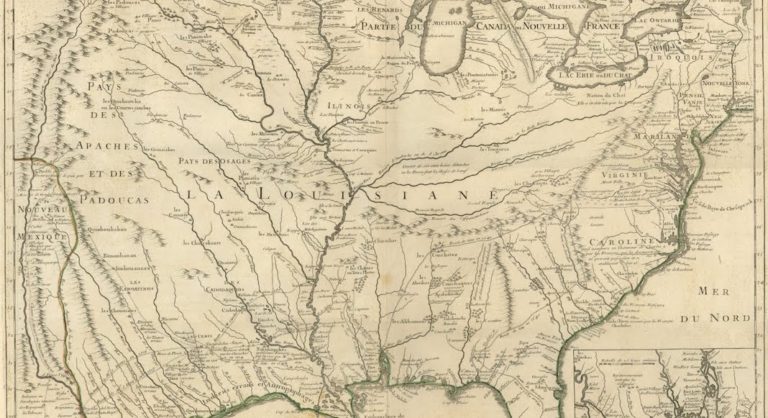

The day before the war started, not many people around the world knew where Ukraine was located and that it was not Russia (a prejudice I’ve faced as a Ukrainian immigrant to the United States myself). And while Ukraine has always been a European nation in the hearts of its citizens, to the rest of the world, it seems to have only earned that place now. Suddenly Ukraine is now on the map, and it is European. There is almost a feeling one can sense that leaders worldwide now realize they may have underestimated the role of Ukraine in the West and, in particular, President Zelenskyy’s necessary participation in international affairs. One can’t help but wonder whether it has been the war that has “turned” Ukraine more European and will change the course of its history forever.

“A while ago, Ukrainians were laughed at and looked down upon everywhere we went. The Ukrainian nation was something sort of Russian. And when the war was starting, I never thought we could win because of this sentiment. We were nothing. No one believed in us. Today, I can proudly say that I am Ukrainian. Now we will be perceived differently. We’ve proved that we are a strong and brave people who can’t be sold, aren’t scared, and are fighting tanks with their bare hands,” says Fitsay who has so far stayed in Ukraine to help the refugee crisis in the western part of the country, though she is expecting her call to war, as a medical worker, any day now.

And yet, while Fitsay is very optimistic and confident in Ukraine’s forces, she notes that there is a larger dilemma at hand. “NATO isn’t omnipotent and yet thanks to its support we have been able to continue this fight. But, I would like to say, that if Ukraine falls to Russia, it won’t stop just there. They will continue to other surrounding nations. And everyone understands this, but they don’t want to get militarily involved.” After a pause she adds, “We aren’t just protecting ourselves at this point; we are protecting all of Europe.”

When I was little, my parents and I drove about an hour to the official, geographic center of Europe located in the small mountain village of Dilove, in western Ukraine. While I’ve recently found out that Ukraine is not the only country to declare itself the continent’s center, and that Germany, Lithuania, Poland, and Slovakia have all staked rival claims, I would still like to believe in it as the center. In fact, in 1887, Austro-Hungarian geographers also noted that the center of Europe landed in Ukraine. So why has Ukraine always been sidelined as a border European nation if it’s smack in the center of Europe?

Ukrainian citizens have always felt European, says Natali Tsubyra from the Carpathian mountains over Instagram messages. Tsubyra was fortunate enough to pick up her three-year-old son from daycare when the war was announced, buy a suitcase with wheels, and walk directly to the Ukrainian border with Slovakia. And yet, an eight-hour line awaited for those on foot. Those driving were greeted with a four-mile queue, which had prompted Tsubyra to leave her car back home. With her son asleep on the suitcase, she worried he would be too cold. She finally made it past the border into Slovakia at 4 am. Her husband, who works in the Czech Republic, picked her up on the other side, and together they drove to safety. Her husband has spent the past few years working in Europe, like many Ukrainians, and most of my classmates’ parents. With Ukraine’s struggling economy, Ukrainian citizens have always had no choice but to look for ways to work abroad which has made their connection to Europe feel even stronger.

“The population of older people has long been unrelated to the Russians, and the majority of young Ukrainians only look in the direction of Europe [and are] focused on democracy— freedom of speech, rights, etc. Look at the leadership of our country — the young people themselves, just as ambitious, all following European ways of life. Or even since the Maidan — the same students that first rallied there, and I was among them — because the policy of Europe is close to us, we need it to make a change in our country,” writes Tsubyra. Maidan happened in 2014 and is known as the “Revolution of Dignity.” At that time, Ukrainian citizens overthrew the acting President Yanukovich in response to his decision not to sign the political associations and free trade agreement with the European Union. Maidan happened when Tsubyra was still in university when she, like many Ukrainians, took to the streets to protest Russian oppression and influence in the government.

Today Tsubyra is safe in the Czech Republic. “Being now abroad with a child, I am received warmly and sympathetically and offered all the help that I need. My mission here is to be human, to be grateful, and not to forget the horror from which I left, or the human kindness. I am sure that if it happened that people from another country fled from the same horror to Ukraine, they would meet the same kindness from Ukrainians. And looking at the cohesion and mutual assistance that exists among Ukrainians now around the world, I am convinced that we deserve to be in the European Union,” she says. These words bring me to tears because there isn’t much to say in response to a statement like this one. In terms of simple humanity, these are the words of a young mother who looks to another future for her child — one without war. One that is European. One that is egalitarian. She mentions that she will indeed return home to Ukraine when the Russian forces leave.

“Vlad Tokar, Andriy Rapoviy…” Yulianna Fitsay writes to me. It’s just a list of names, but she knows I will understand. These are names of our classmates, names of men who have been summoned to war. My last memories with them were at the age of eight. Today, to me, they are little men fighting a big war. One way or another, this is a war that may change the configuration of Europe, drawing Ukraine either left to the West or right back to Communist Russia. And my own classmates, people who I sat in the same room with, will have had something to do with it, having fought valiantly for independence no matter the outcome. They will go down in history. As we say in Ukraine, “Glory to the heroes!”