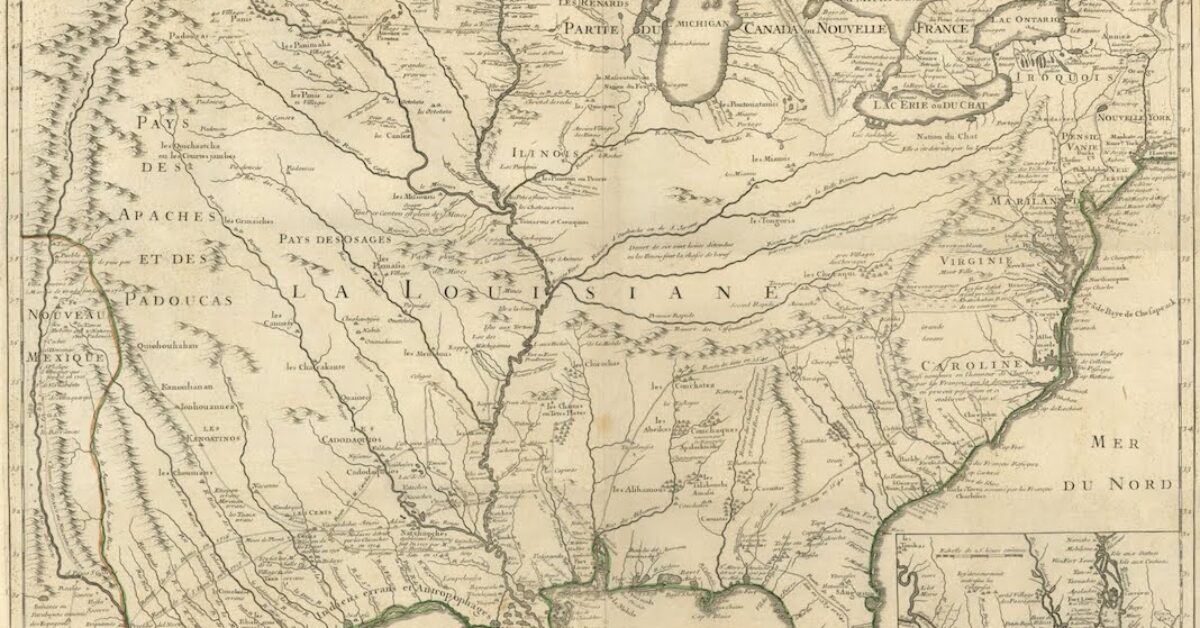

What if Napoleon’s wholesale of more than 828,000 square miles of territory — land that now forms 15 U.S. states, including Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska, as well as swaths of Minnesota, North and South Dakota, New Mexico, Texas, Montana, Wyoming, Louisiana, and Colorado — to the nascent United States of America in 1803 was a mistake, because the blazing expansion of a newly formed nation left to its own devices was a terrible idea?

The Louisiana Purchase could be seen a singular act of isolationism, as an early sign of America’s unwillingness to build a successful country out of multiple national pasts and languages. A continued French presence on the North American content, it could be said, might have lead to different possibilities of evolution, towards a more equitable idea of immigration and assimilation and a fiercer pursuit of social rights.

Put plainly, did America miss the boat on socialism because of Bonaparte’s cash flow problems?

In elementary school, Americans were taught the national myths of Manifest Destiny, complete with the refrains of Schoolhouse Rock’s “Elbow Room,” as though westward expansion into the Louisiana Purchase territory was nothing more than Thomas Jefferson’s initiative to provide the people with more room to roam. In the canon of our great American myth, “going West” has been crystallized as a form of bootstrapping.

Expanding west, the American empire grew yet failed to develop a national identity. France, in comparison, has a strong national identity because it provided the structure to create one, which French historian Jean-Christian Petitfils points out in his book, Histoire de la France (Fayard, 2018): “The United States of America … [was] created around the ideas of liberty and individual rights, without taking into consideration, or at least not until much later, the idea of social justice, social protection, social aids, and the redistribution of wealth. It has been up to the individual to ensure his own social welfare, his retirement, his security… France has not taken this path.”

Petitfils reframes France’s socialism, notably the creation of allocations familiales (monthly social aides given to a large swath of French families with children to lighten the financial burden) in 1931 and of social security for healthcare in 1945. France’s government-run socialism, he insists, is the modern version of charitable work once regulated en masse by the church.

France, writes Petitfils, has never been composed of a single French race, and the Hexagone’s own myth of “nos ancêtres, les Gaulois…” is patently false. Instead, France has, over the course of nearly a thousand years, integrated and assimilated newly acquired provinces (as the Capetians did for several centuries) and peoples, like refugees and immigrants. And while this acculturation of new peoples hasn’t always been peaceful, the idea of assimilation above and beyond simple integration stands out. “The immigrants who arrive on French soil are required to assimilate, or even further, take root here, a gesture that we believe in no way compatible with the conservation of the immigrants origins.”

In the eyes of the French, the United States promotes what they would call the idea of “vivre ensemble,” the simple cohabitation of foreign communities on a single national soil — a notion insufficient to France’s construction of nationhood. And while there are problems with France’s resistance to adapting or modernizing its national identity, it is undeniably a unifying force in the country.

Both ideas put forth by Petitfils as pillars of French national identity can be understood as a French take on the role of government and its responsibility to its people. While radically divergent from traditional American thinking, these two French ideals are not as far removed as they once were. The first regarding socialist protection resembles ideas promoted by Senator Bernie Sanders, which are gaining popularity amongst millennials. The second surrounding immigration appears a more sane, reasonable approach to the “melting pot”; American populations, whether cut across racial, ideological, or religious lines, are not so much melting together as they are co-habitating.

The question of how one forms a national identity then becomes essential. One of France’s key answers to this has been the French language itself, considered a national monument. Will America attempt the same?

Right now is a good time to be French. With Britain’s exit from the European Union, America’s return to an isolationist policy, and China’s advancements on the road to world power, France is starting to look more important today on the world stage than it did a mere five years ago. An uptick in entrepreneurialism, a willingness to lead Europe by Macron, and an economy ready to compete on a world stage with prowess in technology and AI make France a nation to watch over the next twenty years.

So, as America slips into self-indulgence, a question persists: what would have become of America had it remained, at least partially, French? The narrow lesson the French might have imparted is that no man can ever be fully self-made. Citizens evolve within the context of history, governments, and nations that all help or hinder their ambitions and dreams. With this French understanding, could Americans have warmed to socialism and better used government as a force for social good? Would French influence have helped a fledgling United States better understand the necessity for not just pure integration, but assimilation, the long course of forging a centralized identity?

Nor Thomas Jefferson and Napoleon Bonaparte, nor their modern heritors, will ever know.

This article was originally published on July 17, 2018.