New Orleans is a city unlike any other, an American-ish town that looks antebellum, prays Caribbean, sings Spanish, and eats African. But one of its biggest original influences, and one of the most lasting ones, is that of the French. So how exactly did France turn this crescent-shaped city into the major tourist attraction it is today? Well, for that we turn to Ned Sublette’s history, The World That Made New Orleans: From Spanish Silver to Congo Square.

The first thing you might find interesting is that the first French-speakers to make it to Louisiana weren’t coming from Paris, but by way of Quebec. In 1698, the Comte de Pontchartrain, head of the French navy, received news that the British wanted to set up shop at the mouth of the Mississippi. Rushing to beat them to it, he sent Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur de Iberville, and his brother, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, to colonize it. Though Iberville was a war hero, the Quebecois were considered inferior to French natives, so this charge was just about as much of a reward as he was going to get. Iberville Street still runs through the French Quarter, with Bienville parallel to it one block over.

They landed on Fat Tuesday, and decided to name their perch Pointe de Mardi Gras, after celebrating with brilliantly dressed Native Americans all night. “So it was that the first Louisiana colonist celebrated Mardi Gras,” Sublette writes, “partied all day and into the night with splendidly adorned naked people, dancing to a beat” (38). Not so far off from Mardi Gras in New Orleans today.

Meanwhile, the Bourbon era of France was beginning. As convenient as it might seem, that party strip in NOLA’s nightlife district isn’t named for Kentucky whiskey, but for the young Francophone Spanish king Felipe V. But his successor is probably better known as the city’s namesake: Philippe II, Duc d’Orléans.

In 1712, a French commoner-turned-New World fur trader named Sieur de Cadillac conned Felipe V into giving him a fortune to search for gold in New Orleans, though Bienville had already warned him there was none. “Two centuries after the settlement’s founding,” Sublette notes, “Cadillac’s name was a synonym for mass-produced luxury. He thus has the best name recognition today of any French colonist” (42).

But there was no gold, and no one wanted to move to a New World swamp. So the Scotsman John Law took another stab, convincing Philippe II to turn New Orleans into a penal colony. You know the little fleur-de-lis that fill gift shops in the French Quarter? Well, the symbol made its mark (quite literally) on New Orleans because French prostitutes were branded with it when they were rounded up and shipped off to Louisiana. Their history has been memorialized in the popular 1731 novel Histoire du Chevalier de Grieux et Manon Lescaut, more popularly survived by Puccini’s opera Manon Lescaut, likely the only opera ever set in New Orleans (if somewhat anachronistically).

To do more enticing, “The streets of this new capital of La Louisiane would… bear the names of rich Parisians who would never cross the ocean” (53). Then in 1727, the Ursuline nuns moved to New Orleans to evangelize, and their convent remains “the only extant building in New Orleans from the French period” (168). They brought with them music, and the phrase vaudeville (voix de ville), to describe the vulgar popular music they sanitized with edited Christian lyrics.

The few people there were in New Orleans started making money fast. Quebec fur traders (infamous for their Wild West lifestyle and attitude) came down to make money, and the sex workers and criminals brought in from France contributed to a general aura of libertinage. Prostitution, slave trade, and piracy kept the city afloat for more than a century.

When Spain took over in the 1760s, the city was not willing to change its ways easily. “The bulk of the colony’s population was resolutely French speaking and French identified. Spain behaved far more leniently with Louisiana than it did with any other colony” (99), in the hopes that a more gradual approach would avoid an outright rebellion. But a rebellion was what it got, after “a royal decree that forbade, among other things, the importation of French wines into Louisiana” (91). In punishment for the revolt, five Frenchmen and one French Creole were executed by firing squad in the area where Rue des Français, or Frenchman Street, now stands in their honor.

Along with the Creoles came the Cajuns. The land in French Canada that the British called Nova Scotia was once called Acadie, the French term for Arcadia, the Greek pastoral paradise written about by Virgil. But the Acadians, fleeing religious persecution, ended up in New Orleans and became Cajun.

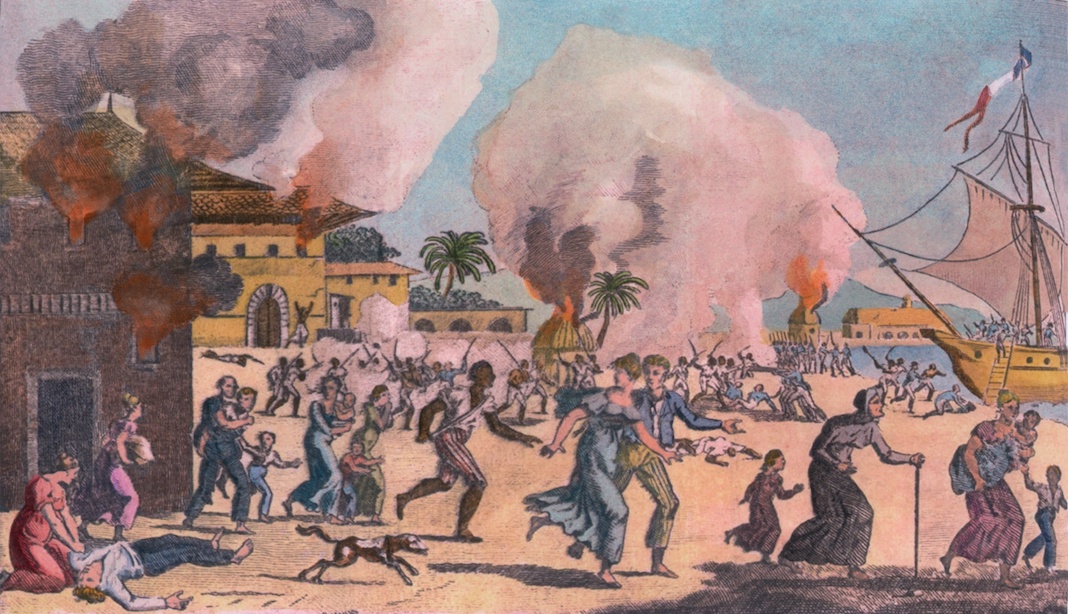

And then there was Haiti. After losing and regaining Martinique and Guadeloupe in a series of wars and treaties with Britain, France decided it wasn’t willing to part with this particular island. “Versailles spent liberally to make [Saint-Domingue] more French” (88), by building cafes, clubs, new infrastructure, and even a printing press. The wealth and depravity of the French in Haiti was such that, “the gentlemen of Saint-Domingue enjoyed an aristocratic lifestyle that French nobles could not have” (138). But when a massive slave revolt, led by a legendary man named Toussaint Louverture, shattered the Western hemisphere, all those gentlemen, and a lot of their slaves and former slaves, wound up in the closest harbor: New Orleans.

With the French Revolution came the abolition of slavery, far ahead of its British and American cousins. This attitude, coupled with Spanish leniency, made for a black population with far more freedoms than in other colonized regions.

A new type of person was being created in New Orleans. French, Spanish, slaves, free blacks, Native Americans, New Americans, British, Haitians, and Cubans met and mixed and became something called “Creole.” With scores of new people interacting came a need for places for them to interact. The first theater in the city, Le Spectacle, was opened by two Frenchmen in 1792. Francophone Haitians and Cubans helped open and perform in a French-language opera company. “Tricolor balls” featured men and women of all races, and dances from all over the world that competed for popularity. “Playing out national rivalries over contredanses seems to have been frequent in New Orleans at that time” (241), writes Sublette, noting an 1802 ball where French and Spanish soldiers nearly began shooting each other over whether to play the contredanse française or the contredanse anglaise (favored by the Spanish).

Mardi Gras as we know it today comes from this French tradition of the masquerade ball, which was incredibly popular in 18th century France and later. Dances like the quadrille were imported to New Orleans with the aid of a French dancing master called “Baby” who taught Creole girls the popular steps of the day. The contredanse française, which is responsible for much of the music that comes from New Orleans, was the most popular of all. “Black musicians rhythmicized the contredanse, creating musical styles which evolved into the habanera (also known as tango) and later, ragtime, as well as the danza, danzón, and ultimately the danzón mambo and its offspring the cha-cha-chá” (104).

The Louisiana Purchase in 1803 turned the region over from France to the United States, but once again, the city refused to give up its heritage. The arrival of the Haitians, “retarded the Americanization of New Orleans for perhaps two generations, reinforcing the critical mass of French speakers in the city” (259). They wrote Louisiana law in French, and took on positions of political power. At this point, the city began subdividing, with French Creoles settling in the older part of town, and the Americans upriver, “practically establish[ing] Canal Street and Esplanade Avenue into national boundary lines” (258).

Another conspicuous name you might find in the city streets is Lafitte, for Jean Lafitte, “Louisiana’s best-known privateer” (265). Born in Bordeaux, Lafitte started work in Haiti, moved it through Cuba, and then up to Louisiana. The pirate gained enormous popularity among French Creoles as a public and economic figure. In a world of complicated trading agreements between nations, piracy became a lifeline and a boon for New Orleans. Want proof of how essential Lafitte’s business was considered? Lafitte’s Blacksmith Bar, Jean Lafitte National Historic Park, and the Lafitte Greenway are just a few examples.

The French flavor of New Orleans is undeniable, and it would literally take a book to outline the details of its impact. But there’s a reason the city doesn’t look like Paris. French wove its way across oceans and all the way down the Mississippi before getting there, thanks to people from the Caribbean to the Great White North who considered themselves French, even if they had never set foot in Europe. New Orleans is proof that France is truly a state of mind, a series of dialects and customs rather than a physical place. It’s a moveable feast, whether you’re eating gumbo or duck confit.