This month marks the anniversary of May, 1968, when strikes and student protests nearly brought down the French government. Frenchly recently talked to three people who participated in or lived through these tumultuous times about their experiences: Dr. David Ross, Professor of French at California State University, Fresno, who was 27 and in Paris with his wife, doing doctoral research on a Fulbright scholarship; Monique Jaulin, then a 20-year-old part-time university student who was also working part-time; and Christian Detaux, who was 18 and working in a factory with 3,000 employees.

How did you first experience the strikes and protests?

David Ross: At the beginning of May, my wife and I were on vacation in Spain and weren’t paying much attention to events in France. But once we returned, we discovered that Paris was not itself! Newspapers weren’t being delivered, no international phone calls or mail were possible. Paris was largely cut off from the rest of the world.

Monique Jaulin: My company went on strike so I couldn’t go to work. I heard that the police were beating student demonstrators, and I was shocked — they could have been beating me! I wasn’t very political at the time but I knew I had to get involved. A friend at the Sorbonne invited me to a meeting in the Latin Quarter. Later I joined a group of students going to a street near Odeon to build a barricade. We dug up cobblestones and used them and some wood to build a wall. We were near the main battles but it wasn’t too dangerous — the worst part was the tear gas. We had a big pile of cobblestones to throw at the police but they never came close enough.

Christian Detaux: The craziness in Paris started with the students and then we ouvriers joined in. At my factory, workers went to all the managers and gave them a choice: join the strike or leave. You should’ve seen how fast they got out. Within a few hours we had completely taken over. We had teams that guarded the place day and night so no one could break our strike, and also to make sure that none of us drank too much and caused trouble — a little beer was OK but that was it. After a few days I went into Paris to man a barricade.

As the strikes continued, did your feelings about them change?

DR: After a few days my wife and I decided to leave Paris because we felt very uneasy. After a week away, we heard that the strikes were ending so we decided to return to Paris. When we got home I was pleased to discover drivers were parking cars on the sidewalk and the police weren’t giving out traffic tickets. For several weeks I brazenly parked on the sidewalk near our apartment. When the police finally did begin to issue tickets, I just tore them up.

MJ: It was really exciting at first, fun actually! But after a few days, I left the barricade because I wasn’t getting much food or sleep, and it was getting more dangerous.

What made you decide to join or not join the protests?

DR: I had no intention of going to witness violence and perhaps become involved involuntarily.

MJ: It was a matter of solidarity. It reminded me of the attempted coup against the French government in 1961. When my father heard about it, he rushed into the street and joined a demonstration against the generals. Sometimes you have to get involved for what you believe is right. For him it was 1961. For me it was 1968.

CD: I was young and foolish then… and it was fun.

What was the reaction of people in Paris?

DR: Most everyone wanted to distance themselves from the violence, French and foreigners alike.

MJ: For my generation, May ’68 was an explosion of joy and hope. In the 60’s we kept getting more and more freedom, with rock music and the pill and things like that, and this felt like it was the culmination. But my parents’ generation wasn’t happy because it was like a revolt against them and their authority.

CD: At first, just about everybody in Paris was in favor of the strikes and protests. But then stores started running out of food because there weren’t any deliveries. Public transport was on strike and gas stations were empty, so people had to walk to work. After a few weeks people were fed up and turned against “the revolution.”

How was life in Paris different after May ’68?

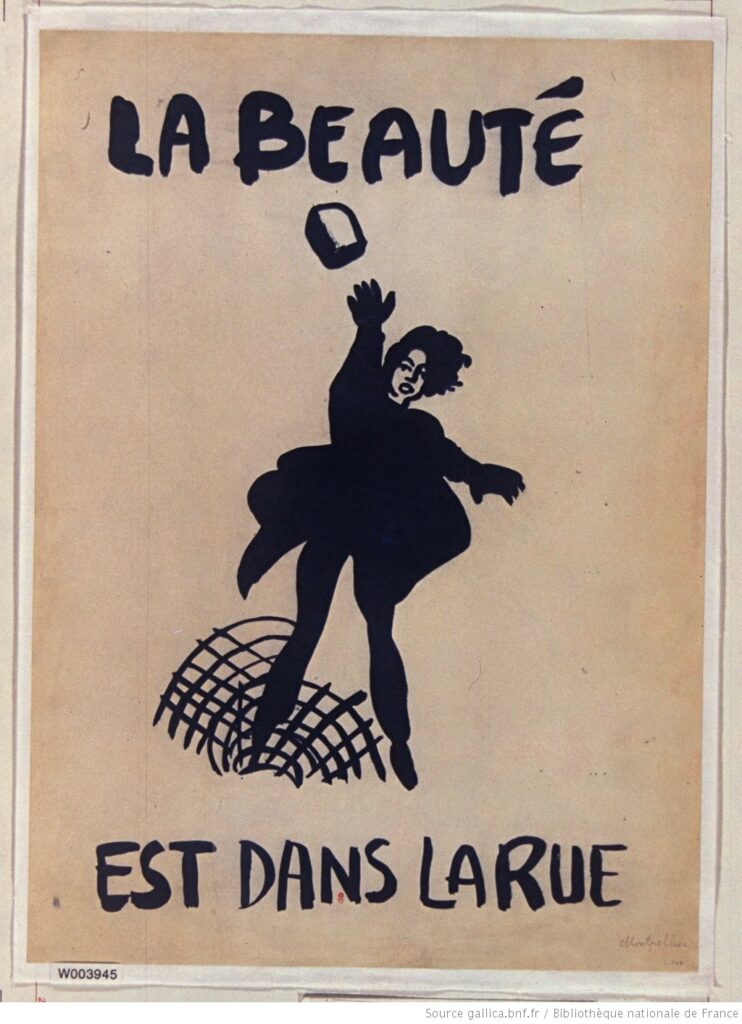

DR: Security remained tight for some time. For several years thereafter, any gathering of five persons or more was strictly forbidden. Many of the streets in the Latin Quarter were covered over with asphalt to prevent the cobblestones from being dug up and used as weapons again. At the same time, nearly everywhere people seemed to relax and became less formal in the way they dressed and interacted. It became more difficult to distinguish [European] students from fellow American university students.

MJ: May ’68 changed my life. I felt like I could do whatever I wanted and could make my own decisions. A couple of months after things calmed down, I decided to go to India and live there for a while. It was a way to express my newfound sense of freedom and live the way I wanted to. France in general gained this sense of freedom as well. People became less blindly conformist, doing only what they were told to do; they were more willing to demand their rights.

CD: The strikes helped us workers a lot. We got much better pay and more time off.

Do you think about May ’68 differently today than you did then?

DR: I haven’t changed my opinions very much. I think the events of 1968 constituted a “binge,” a setback that the French economy could ill afford. The continuing French Revolution, begun in 1789, had made another of its periodic intrusions that occur in France from time to time.

MJ: Like the student leader “Dany le Rouge” Cohn-Bendit, I once believed in utopia. And like him, I’ve become more pragmatic over the years, still believing that another world is possible but that we may have to wait a little for it.

CD: In 1968 I supported better pay and shorter hours for workers because they were necessary. But looking back, I see that we went too far and now many French companies have trouble competing in the global marketplace. The only way to succeed is to work hard.

Keith Van Sickle splits his time between Provence and California. He is the author of the recently-published An Insider’s Guide to Provence and the best-sellers One Sip at a Time: Learning to Live in Provence and Are We French Yet? Read more at Life in Provence.