It all started with a commission for an article on the history of cassoulet. The journalist, Sylvie Bigar, a travel and gastronomy specialist in New York City for many American newspapers (The Washington Post, The New York Times, etc…) went to the medieval French town of Carcassonne to write about the Universal Cassoulet Academy. A straightforward report, nothing extraordinary at first glance. “I thought that in one week, it would be wrapped up,” she recalls. Except that there was that first bite of cassoulet. “I became completely obsessed with this dish, without knowing why. That trip changed my life,” she writes.

“Digging under the crust”

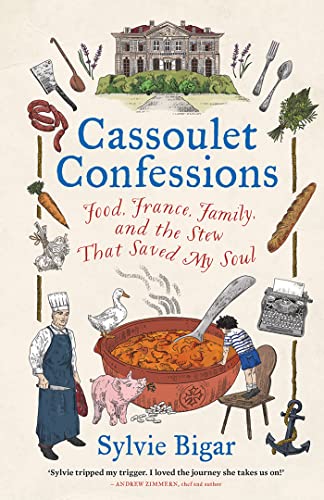

It is this incredible gastronomic and emotional journey that the author offers in Cassoulet Confessions: Food, France, Family, and the Stew That Saved My Soul, just published by Hardie Grant Books. A funny and tender book in which two stories intertwine, that of a typical dish from the southwest and the intimate and personal story of a complicated childhood. Through these two stories, Sylvie Bigar takes us into the unknown world of one of the best kept recipes of French culinary heritage and also on her personal path to self-discovery.

The road was long for Sylvie Bigar, and she tells it with a lot of self-mockery and humor. She first had to return to the region of Occitania, in southwestern France, to learn to cook with the “Pope of Cassoulet,” Chef Eric Garcia (a pseudonym, to respect the privacy of the cook), a real character in the memoir, who is at the same time a “cook, poet and philosopher.” It is at his side that this “little American girl,” as he calls Bigar, learns to cook from A to Z. “There was not a powder,” she tells French Morning, “not a dye, that was not homemade.”

After her long initiation, Sylvie Bigar also had to isolate herself to write, in a writers’ house, La Muse, in the Black Mountain in southwest France. And it is in the silence of the place that she began “to dig under the crust,” to discover her long suppressed childhood memories. She grew up on a large family property in Geneva, with its centuries-old trees in a garden that once belonged to Charles Bonnet, a botanist and friend of Voltaire. Her father was a rigid dandy bathed in nostalgia for the golden years of the Côte d’Azur; her mother, a literature buff with Jewish roots, shattered by the death of her only son in the Vercors in 1944 (the hero of a future novel Sylvie Bigar is working on); and her three sisters, 8, 10 and 12 years her senior, whose departure from home left her to grow up as an only child.

From a dish to family roots

Dysfunctions, family secrets, taboos, feelings of betrayal… it all came back to her while she wrote. “I realized that everything was a question of opposites and contradictions,” explains Sylvie Bigar. Between her Swiss bourgeois upbringing and the culture of this southwestern chef, Garcia; between the austere dining room of her childhood, “as convivial as a coquette morgue,” she writes, and the warmth of the Garcia family; between the rustic food that make cassoulet and a household where “where we didn’t eat beans, almost no pork,” Bigar began to understand that her obsession with cassoulet “had actually come to me,” she says, “from very far away.”

The book is unpretentious and evokes what anyone wants: the need to know where one comes from. “I wanted to transmit this deep France. I wanted Americans to go there, to discover something other than Provence, Paris and the Riviera. I also wanted the French to rediscover,” as she did, “a taste for authentic France. I think the French are very attached to their traditions, especially in terms of food. We all want a good cassoulet, a good sauerkraut, a beef bourguignon. These are our roots.”

At the end of her book, Sylvie Bigar reveals several cassoulet recipes: three that make up what she calls, “the trinity of cassoulet.” There is one from Toulouse, a personal recipe, and another for an express cassoulet, “when you don’t have two or three days to cook,” developed with her culinary expert friend, Marion Sultan. And, finally, there’s a “surprise” recipe.

The book is written in English, “because I’ve been in New York for 40 years and I write in English. But I dream of having it translated into French.” In the meantime, Cassoulet Confessions has just been released in the United States and can be read in one sitting. A book that, in the words of chef Dominique Ansel, “feeds the mind, the soul and the stomach.”

Elisabeth Guédel is the Editor in Chief of French Morning.