Le chocolat, un apartment, un livre; la bière, une question, une cerise — for English speakers, it can be disorienting to think that chocolate, an apartment and a book are masculine in French, while a beer, a question, and a cherry skew feminine.

English is a non-gendered language when it comes to pronouns (“the,” “a,” and “an” are gender neutral), while French and a slew of other languages like Spanish, Polish and German assign genders to all nouns. While this can feel confusing and unnatural for language learners, native speakers rarely think about this aspect of their mother tongues. For them, le chocolat and la bière are simply thought of as a unit, with the pronoun playing such a natural part of the word that it’s easy to forget it’s even there.

But just because French speakers think that these genders don’t matter, doesn’t mean they don’t. Gendering nouns actually affects the way that people perceive objects and ideas.

Social scientists and researchers have been trying to figure out how language affects cognition and psychology for hundreds of years. In the mid-1900s, the hypothesis of linguistic relativity — also known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis — gained popularity, proposing the idea that a language’s structure influences how people think. Linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf, after whom the theory is partially named, pointed to ideas such as how the Hopi people, a native American tribe, didn’t have a word for “time,” which he thought greatly influenced their culture. The same was true, he believed, for all societies, meaning that linguistic differences fundamentally changed how people experienced the world. Although Whorf’s theories have since ebbed in and out of favor with linguists in ensuing years, this school of thought undoubtedly plays an important role in the history of linguistic theory.

This brings us back to the French and their gendered lexicon, which is more important to cognition and psychology than most people think. In the early 2000s, linguistic researchers brought in native Spanish and German speakers and compared how they described various objects, all of which had opposite genders in Spanish and German. The results were clear: gender affected how people perceived the objects.

When asked to describe the word “key” — which is feminine in Spanish but masculine in German — the subjects’ answers were influenced by the gender of those words in their mother tongues. The Spanish speakers described “key” in feminine terms such as “golden,” “intricate,” “lovely,” and “tiny,” while the German speakers used traditionally masculine descriptions like “hard,” “heavy,” “jagged,” “metal,” and “useful.”

In a 2017 research paper, Izbella Haertlé conducted another study, this time with Polish and French speakers, to reexamine this idea that gender influences perception. In this case, the research team explained that they were creating a movie where inanimate objects and animals talk to one another, and the participants had to choose a corresponding gender voice for each word. Unsurprisingly, the speakers tended to assign either masculine or feminine voices that corresponded with the given linguistic gender, once again supporting the previous academic research that gendered language does, in fact, affect perception.

Does this body of research mean that the French and other speakers who interact often with gendered language have a totally altered worldview compared with those who grow up with gender-neutral languages? Not necessarily, and it’s a question that linguists have been trying to understand for a long time. But it does shed light and open up the conversation about how gendered language can affect cognition, especially in subtle and often unconscious ways.

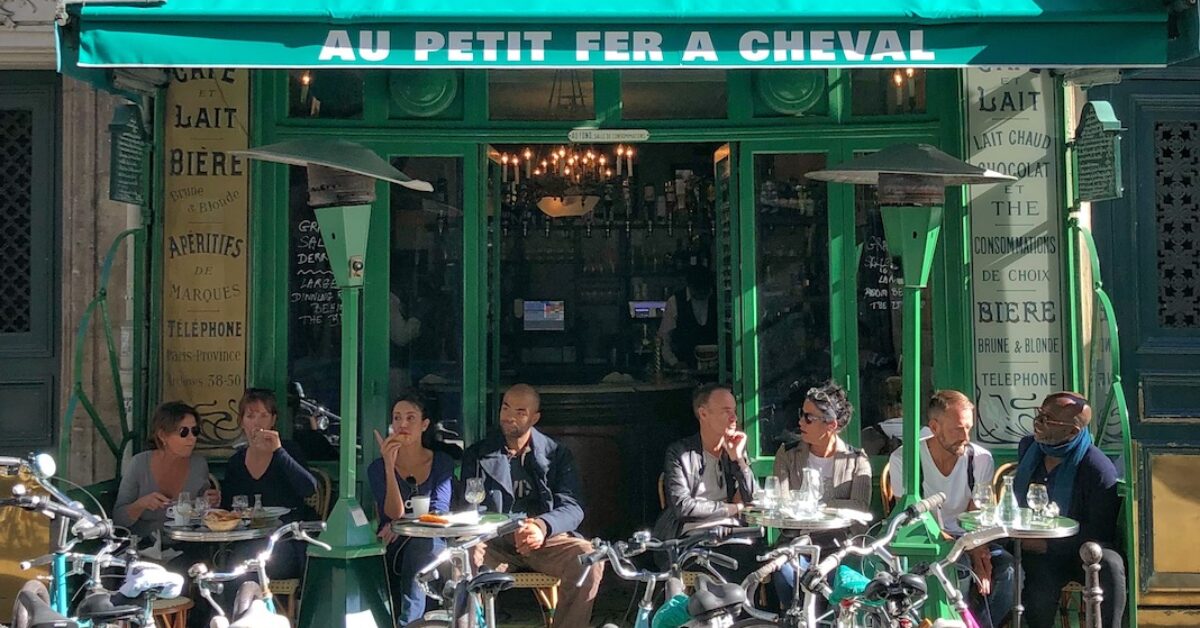

So the next time you find yourself wondering, “but really, why is it le chocolat and la bière?” remember that you’re not just being difficult. In fact, you might just be unearthing age-old questions about gendered linguistics, one piece of chocolate and cold beer at a time.