Constance Debré thinks her little boy, Paul, is “great” and “a little mensch.” Even so, she wonders why the love between mother and son is considered so sacrosanct, different from other forms of love. Or, at least, that is her question by the time she pens Love Me Tender, an autobiographical novel that she published in France in 2020 and was released this fall, in Holly James’s translation, by Semiotext(e). Why shouldn’t son and mother, she wonders, “be allowed to stop loving each other.” Why can’t there be a break up, as with other forms of love? It’s not that she changes her mind about Paul per se, but after years of battling her former husband, Laurent, for the mere right to see her son, she has had it..

It’s true that Debré has changed (dramatically) since she left her marriage. She has quit her job as a criminal defense lawyer, forgone the accompanying income, and streamlined her life in order to write. Debré explains that it’s not just her sexual preference that has announced itself. For her, “(H)omosexuality means just taking a break from everything. That’s exactly what it is, a long vacation, expansive as the sea with nothing on the horizon, nothing close to it, nothing to define it. That’s why I quit my job. To be both the master and the slave, the only one responsible for setting limits. Work, family, apartments, finito. And you can’t imagine how good it feels.”

If she stayed bourgeois, she suspects, if she didn’t “opt out” of so many things, her sexual preference would not have been threatening to Laurent and others. “But that wasn’t an option,” she explains, “that’s not how it works, I didn’t go through all this for more of the same. I did it for a new life, for the adventure.”

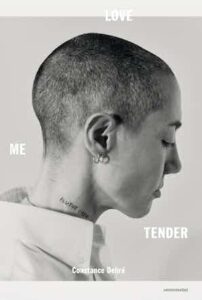

Her adventure is simultaneously sensual and ascetic. She sleeps with multiple women, even as she sheds possessions and additional things. She shaves her hair to the skull, limits herself to three t-shirts, a leather jacket, and two pairs of pants. Eventually, when she seems to be losing her case to continue regular visits with her son, she trades her one-bedroom apartment for a monastic one-room apartment furnished with only a bed.

The only thing Debré doesn’t want to abandon (her son) is taken from her by Laurent. His pedophilia charge means Debré cannot see Paul for months on end, and then, when visits are allowed, those visits are minimal (one supervised hour). Outside forces reduce her life to waiting for the outcome of her case, while she focuses on her primary activities—lap swimming, writing, and sex, though sex sans love or connection.

As a mother, Debré played with her son. Together, they did things. Park visits, bike rides, whatever. Now forced into one-hour conversations in the presence of authority figures, they talk warmly, but run out of things to say. No surprise. Her son is a boy, not Wallace Shawn schmoozing in My Dinner With Andre. It is never clear whether Paul is even old enough to articulate his own desires, especially given what he says in Debré’s presence doesn’t always align with what he is reported to have said (in the case files). Maybe he’s been coached. Maybe he’s trying to please his father. Maybe he is traumatized by his changed mother.

As her case drags on, Debré whittles herself further, abandoning her studio apartment for couch surfing, more swimming and fucking (her preferred term). She’s impatient with those who assume that she must have money because of who she is, the details of which French readers would likely know. The flap copy of the 2022 translation of Love Me Tender says Debré is the “daughter of an illustrious French family,” a phrase that may lead Americans not-in-the-know to Debré’s Wikipedia page for the details (her father a journalist, her mother a model, grandparents and uncle—all significant French statesmen).

At 165 pages, Debré’s chronicle leaves a lot out, and it’s hard not to want to grill her, as not everything in this book seems to cohere. Why was a woman who defended murderers and pedophiles so unable to make the illegitimate case against her come to end? Why does she insist on her poverty when the plain fact is that though she steals groceries, because she no longer has savings or a salary, it’s the wealth of friends who put her up and buy her drinks and enable her to live as she does, before her book contract money comes through? At one point, she is staying in an unused bedroom in an acquaintance’s apartment in the Marais, that tony neighborhood, and she makes a comment about the housekeeper being unable to clean the bedroom because she and her lover du jour are there. Might not that housekeeper be in need of some of that radical freedom and the same chance at absolute self-determination that Debré grabs for herself?

It wasn’t just the housekeeper that made me chafe, even as I admire Debré for her strength and her project. On the one hand, she genuinely lives as she wishes, rejecting the patriarchy and all that comes with it. On the other hand, she claims, not entirely persuasively, that she does not really care about anyone or thing, and her manner with her sexual partners is Camus ho-hum: “Mother died today. Or maybe it was yesterday, I don’t know.” Of course, emotions creep in, all the same. She is genuinely grieving, as she is waiting, in anxious suspension, eager to hear about her case. In the meantime, she finds the sound of children playing (when she cannot be around her own child) unbearable, though she grumbles at notions about how she “must” be feeling about her situation.

Debré’s devotion to her radical freedom makes her seem uninterested in anyone but herself. Granted, she’s whip smart and undeniably compelling, even though her experiment has a touch of narcissism (me, me, me, me on my own terms). Her sexual bravado (the tallying of conquests), in the end, seems rather… well, male. Ironically, the one convention she cops to caring about is beauty. She talks about her swimming, how it shapes her physique, and how important it is to look good.

Still, Debré’s story is undeniably interesting, her ideas provocative, and her writing propulsive. She purposefully writes in run-on sentences, piling up short statements for rhythmic, intellectual, and emotional effect. Whatever the terms of your own life, Love Me Tender will make you think about the possible shackles of love and motherhood, and the limits and virtues of self-determination.

Debra Spark’s fifth novel, Discipline, will be published in 2024. She teaches at Colby College and in Warren Wilson College’s MFA Program for Writers. She writes a monthly book review for Frenchly, under the title Bouquin.