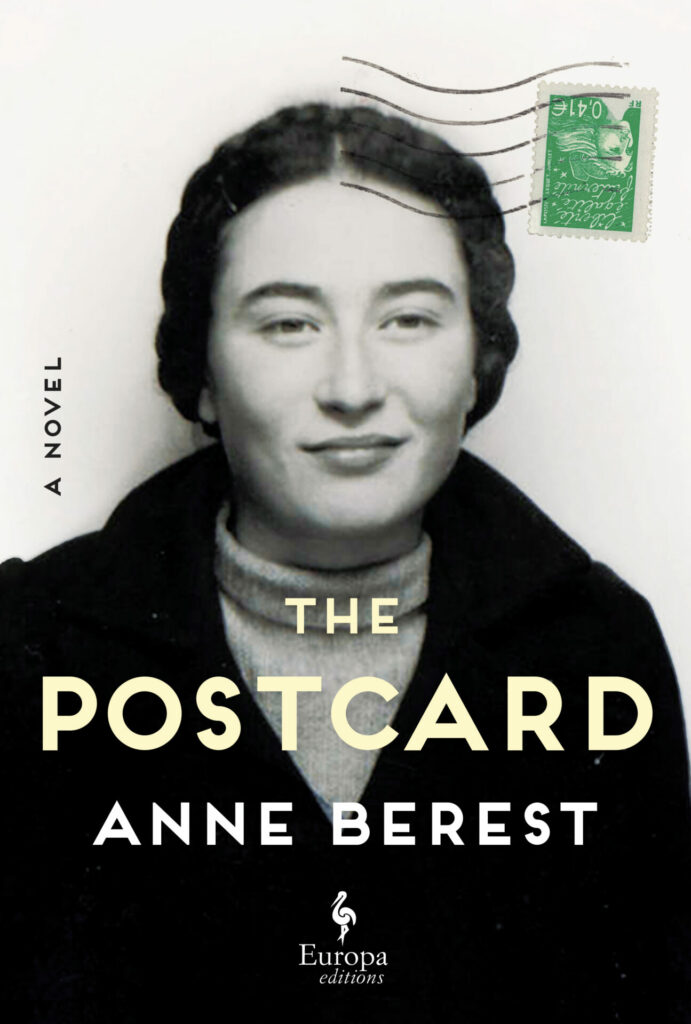

What does it mean to be Jewish and a descendant of a Holocaust survivor, to have no relationship with Judaism as a religion or a culture but to associate your historically marginalized identity largely with death? Though Jewish, writer Anne Berest grew up in France with no exposure to Judaism. She understood herself to be Provençal on the maternal side, and Breton on the paternal. She didn’t even know, till she was much older, that her maternal line, the Rabinovitch family, came from Moscow. Her uncertainty and emotions about her Jewish identity animate her new novel, The Postcard.

Despite Berest’s parents’ secular humanism and socialist leanings, the word “Jew” kept returning throughout Berest’s life “like a dark star, like some bizarre constellation, surrounded by a halo of mystery,” she writes. Berest’s maternal grandmother—born Myriam Rabinovitch—survived the Holocaust, though Myriam’s parents and younger siblings, Nóemie and Jaques, were murdered at Auschwitz. Whether from survivor’s guilt or PTSD, Myriam is largely quiet about her past.

When Berest was almost forty, an anti-Semitic incident at her daughter’s school triggered her desire to learn more. A boy told Berest’s daughter that he didn’t want to play with her because people in his country—his family was Moroccan—didn’t like Jews. The circumstance made Berest think about an anonymous postcard that her mother, Lélia, received at her address in 2003. The card was addressed to Myriam, and written on it were the names of the four relatives who had died in the Holocaust, and nothing more. The penmanship was peculiar, as if the author was trying to conceal his or her identity.

What was this about, and who sent the card? Unsettled, her family considered the mystery, came to no conclusion, and put the card away.

At the time, Berest was 24. Ten years later, on bedrest at her mother’s home, and waiting for the birth of her first child, Berest wanted to know about the line of women from whom she came. She asked her mother, Lélia, to tell her the story of the Rabinovitches. “Just like in all the Russian novels,” her mother begins, “it started with a pair of star-crossed lovers,” and, indeed, The Postcard does suggest a Russian novel in its epic sweep. But it also has the intimacy and emotional honesty of a memoir, plus so many lessons relevant for the present moment.

The first section of The Postcard is a version of the mother’s narrative, starting with the Rabinovitch family in Moscow and then following them as they flee to Latvia, Palestine, and, ultimately, France. The story is occasionally interrupted with dialogue, often Berest asking her mother to clarify details. At one point, Berest asks her mother if she is embellishing the story, and her mother says, “No, darling. I haven’t made up a thing. All I’ve done is research and reconstruct.” For her own part, Berest calls The Postcard a “true novel,” as she appears to be doing the same, combining what reads-as-memoir with a historical novel based on her own and her mother’s voluminous research.

After the initial 200 pages of the nearly 500-page novel, the narrative reshapes itself to follow Berest’s decision to finally figure out what that mysterious postcard was about. The narrative then see-saws between Berest’s present-day investigation and the family back-story, focusing on the story of Myriam’s escape from authorities, her participation in the French Resistance, and her marriage to Vicente Picabia, the troubled son of the famous artist Frances Picabia and his first wife, Gabriëlle Buffet-Picabia, who was also a Resistance fighter (and, at one point, Marcel Duchamp’s lover and muse). Vicente has married Myriam, in part, because she is a Jew and thus forbidden. One consistency in Vicente’s inconsistent life is his desire for the forbidden.

Though partially a mystery and even a spy thriller, The Postcard ultimately reads like an absorbing and tragic biography of an extended family, ripped apart by the cruelties of Vichy France. In an English translation by Tina Kover, the book (released on May 16) is lucid and propulsive, full of the expected concentration camp horrors and war-year atrocities, but it is also fascinating and informative, infused with multiple surprises and redirections, plus minor appearances by artists and writers like André Gide, Sonia Delauny, and Samuel Beckett, all of whom figure in the story. (At one point, Myriam escapes in the trunk of a car driven by her mother-in-law. Her companion in the boot is a silent Jean Arp.)

It is no surprise that this novel has already won multiple literary prizes and was a bestseller when first published in France in 2021. Passages quoted from actual letters, e-mails, and journals make it clear how much literary accomplishment there was (and is) in the family line, including the narrative talents of the young Nóemie, Myriam’s sister who was working on a novel just before her concentration camp death. Towards the end of The Postcard—I’ll give this one spoiler—Berest discovers both Nóemie’s novel-in-progress and a coincidence that might seem to bless both Berest and The Postcard: Nóemie named her protagonist Anne

Debra Spark’s new novel Discipline will be published next year. She writes the Bouquin column for Frenchly. Read Debra’s recent reviews of Eastbound and The Disappearance of Josef Mengele.