People who live through times of war, revolution, or profound distress sometimes experience time differently than the rest of us. Decades of history merge, day and night collapse into one, and moments lengthen and intensify. Maylis de Kerangal captures this alteration of time beautifully in her jewel of a novel Eastbound, which is about two strangers on a train. It pits the physical enormity of Russia, totalitarian oppression, and cultural isolation against individual desire.

The novel’s protagonists are going through personal revolutions. Aliocha is a 20-year-old Russian conscript. With 100-plus other conscripts, he’s headed east on the Trans-Siberian railroad. The young men don’t know their final destination or what they will be asked to do when they arrive. Back home in Moscow, those who could bribe their way out of the military or get a girlfriend pregnant are exempted. Aliocha has not been so lucky.

The novel’s other primary character is Hélène, an older Parisian woman, also riding the train. She has spontaneously boarded, in order to leave her Russian lover, who manages a Siberian dam. He entices her, but she can no longer abide living in a place where she is so profoundly alone, especially as she does not speak the language.

Hélène can’t talk with Aliocha either, but the two meet just when Aliocha decides to desert. Though Hélène has chosen the life she has been living, and Aliocha has been forced by the government onto the train, both are saying an abrupt no to what has been, and trying to say yes to … well, they don’t know what.

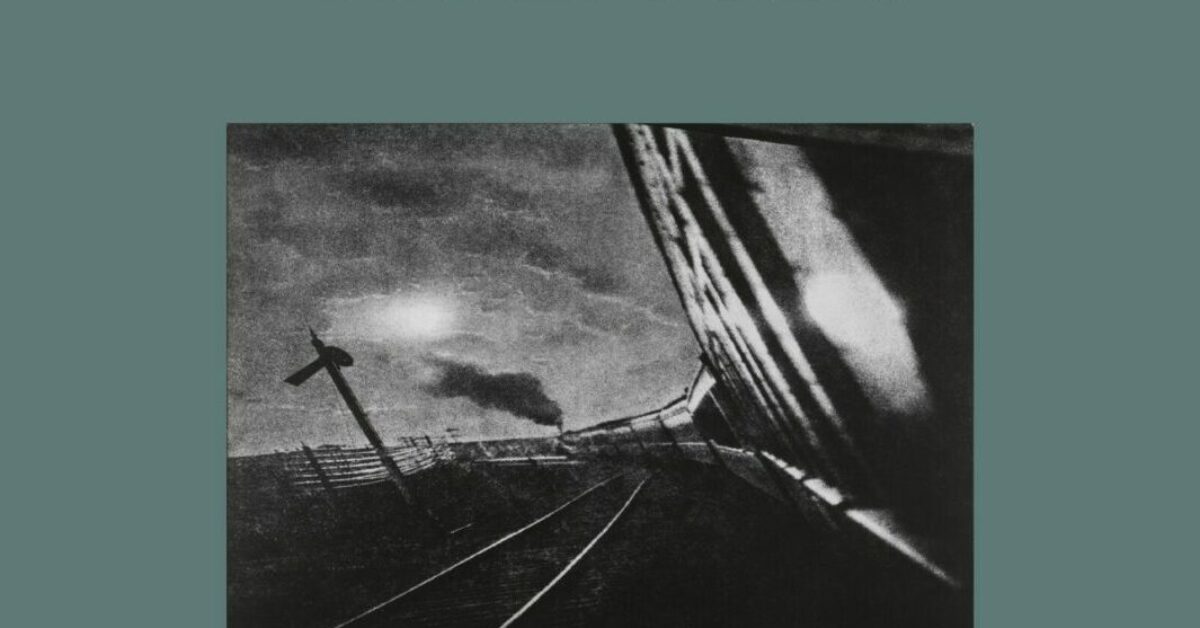

The novel opens on the precipice of this change, a high stakes drama for Aliocha, and one into which Hélène is drawn, even though the two communicate primarily with facial expressions and gestures. The novel never leaves the liminal space of the train, save for moments of memory to establish the characters’ respective situations. What de Kerangal does for time, she also does for space, suggesting both the tight compartments of the train and the enormous expanse of Russia as it passes through the train windows.

With extended sentences that replicate the rhythm and length of the moving train, de Kerangal describes the journey, as well as the focused attention one pays to the world, when the nature of your life is about to be determined. Here’s Aliocha in a back car of the train:

“The back window is free again and Aliocha leaps to it, magnetized to this unique focal point on the world—like an eye in the back of your head—captivated by the sight of the tracks that hurtle backwards into the landscape, striped ribbon alternating light and dark, stroboscope lighting up his face, and soon, hypnotized, he touches the point in space where the forest swallows the still-hot rails, engulfs the ties in a well of mystery, bit by bit he forgets the train car, forgets the guys smoking behind him and the smell of skin suctioned to the walls from sweat, all he is now is this vanishing point that devours space and time; he coincides with it, grows obsessed, ready to pour himself into the great black hole, to tumble in headfirst, anything but Siberia, anything but the barracks, so concentrated in this moment that he doesn’t hear the guys coming up behind him, bellies out, jostling him, sandwiching him, then pushing roughly and pressing him against the wall as though trying to shove his body in it.”

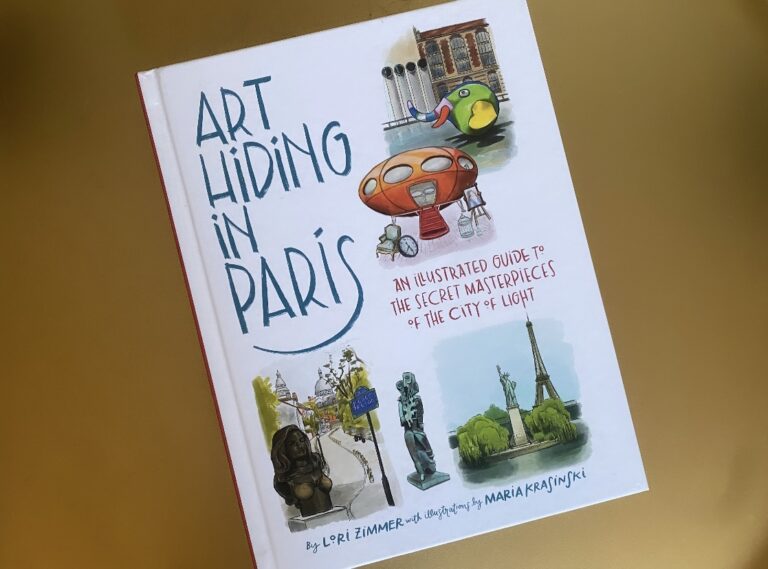

Eastbound is only 125 pages long, and it is a physically small book. That (fairly typical) de Kerangal sentence fills a page, though the words merely describe a man looking out a window, and then being jostled by ruffians.

Later, we get centuries of Russian history in not much more space. Hélène notes that she has “a tragic and patchy image of Russia,” then compresses post-empire Russian history into a page-plus sentence, as she lists what she pictures, things like Lenin’s “fevered face,” the 1979 Afghanistan invasion, the “smile of the billionaire” who purchased the Chelsea Football Club, the “Chechen nightmare,” and Putin’s tough exterior.

Inner and outer immensity is luminously portrayed in this novel. The narrative might tunnel in to describe Hélène registering the “slowed down flow” of Aliocha’s blood, as he sleeps in her train compartment, or pull back for the monotony of what’s outside the train window: “[It’s] still the same forest, the same slender trees, the same orangey trunks, a forest identical to itself to this extent is insane.”

Actions often have a subtext in a totalitarian state. The desire to be free co-exists with an awareness of the danger of enacting that desire. As such, good and evil are perverted, people making choices (sometimes skewing brave, sometimes self-interested) that they might not otherwise make. A train employee helps Aliocha, just because she senses his situation, despite the clear risks to herself. Early on, Aliocha is the victim of meaningless violence (those initial ruffians), and he registers his commanding officer’s malevolent nature. And yet, when he needs to, he is self-protectively violent himself.

Eastbound was originally published in France in 2012. References to cell phones and Lady Gaga suggest the book was then contemporary. Now the book has been rereleased—in a gorgeous English translation by Jessica Moore—at a time when real-life Russian conscripts are headed westbound. That dark irony makes Eastbound feel all too relevant, a reminder that the world is everything, but so is an individual life.

Debra Spark’s fifth novel, Discipline, will be published in March 2024. She teaches at Colby College in Maine.