If you haven’t heard of Claude Cahun, you’re not alone. In talking about art—particularly French art (particularly 1920s Surrealist French art)—women and non-binary folks tend to get left out of the conversation. But in honor of Pride Month, it’s time to talk about a very special artist whose works feel contemporary even a hundred years later.

Lucy Schwob was born in 1894 to a prominent Jewish family in Nantes. But at the age of 18, while attending the Sorbonne in Paris, they adopted the name Claude Cahun. Claude, which can be used in French for a man or woman, was chosen to be a deliberately gender-ambiguous canvas upon which Cahun could create some of the most poignant Surrealist artworks of the 1920s and 1930s. Though the term non-binary was not in common use at the time, in their 1930 autobiography, Aveux non Avenus (published in English as Disavowals), they said of gender: “Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

Their lifelong creative and romantic partner, Marcel Moore (also a pseudonym, for Suzanne Malherbe, who later became Cahun’s stepsister), collaborated with Cahun on writings, novels, sculptures, and collages. They hosted salons at their home, where prominent 1920s figures like Sylvia Beach (founder of Shakespeare & Co.) and André Breton (author of The Surrealist Manifesto) were often found.

Cahun was best known for their self-portraits, which were elaborately staged, and involved costumes and visual trickery to disrupt preconceived notions of gender. Short, or often shaved, hair was a frequent feature of Cahun’s aesthetic, and they used makeup as a tool for camp or character rather than feminization. “Under this mask, another mask,” goes one of their famous quotes. “I will never be finished removing all these faces.”

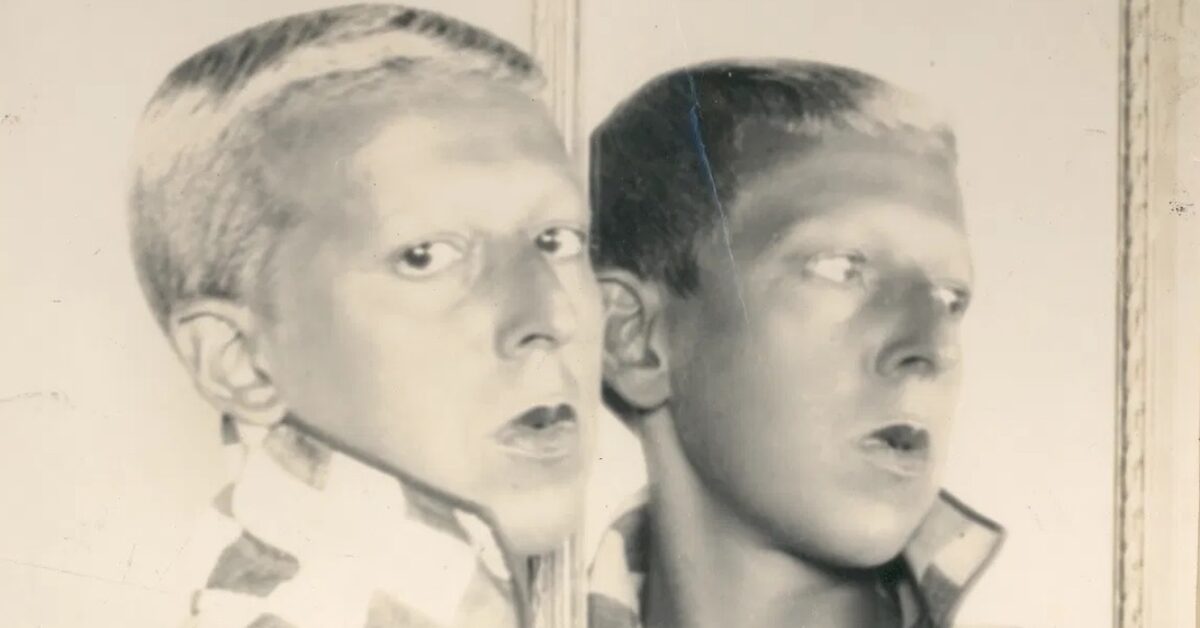

One striking characteristic of many of their self-portraits is their unapologetic eye contact with the viewer. In an untitled self-portrait from 1928, they adjust the collar of a checkered coat in the mirror, turning, mouth slightly open, as though someone has just called their name. The mirror-self stares too, off over their shoulder, neck exposed in a provocative pose.

Doubles are often a feature of Cahun’s work, generally identical or near-identical doubles that force you to look for the difference, only to realize there isn’t much of one. It’s a striking commentary on gender binaries and their inherently arbitrary nature, but it’s far from overly serious—in fact, it often errs on the side of playful. “Que me veux-tu? (What do you want from me?)” shows a Siamese twin-esque Cahun with two shaved heads in conversation, one appearing to say something shocking to the other. It’s both comedy and criticism, fun and function.

Despite this, Cahun was not a star in their own time. Cahun and Moore escaped France for the island of Jersey during World War II, where they spent their days working on anti-Nazi propaganda. Much of their art fell into obscurity, and was nearly lost after their death. Their photographs were never exhibited, their writings dismissed as convoluted and experimental, and it wasn’t until the 1990s that their work resurfaced. It was considered timely then, and has only become more so, as critical gender theory becomes common parlance and Gen Z’s practical optimism pushes white cishet culture farther and farther out of vogue.

In 2018, the city of Paris renamed a street in the 6th arrondissement Allée Claude Cahun et Marcel Moore to celebrate the two artists and lovers. Many of Cahun’s most well-known works can be found at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Cahun is finally getting the credit they deserve, as someone who redefined what it meant to be a person operating in an aesthetic space that is so frequently gerrymandered to serve the existing power structure. They were an artist and activist, an LGBTQ icon, and a reminder that the important discussions we are having today around gender and sexuality are not trends, but instead part of a much longer dialogue about queer representation and its many faces.