Language has always been a critical part of both personal and national identity. It creates a common bond between people who may have nothing else in common and is a tool with which we communicate our experiences and our lives. The words, dialects, and accents we have or choose to utilize show where we come from, our beliefs, or the cultures we grew up in — our identities. Language then acts as both a unifier and something that makes differences clear.

France, a country incredibly invested in the concept of a unified and regulated language, is in linguistic turmoil. Tensions have been simmering between traditionalists, who want French to remain the way it is, and advocates for the gender-inclusive French movement. These activists hope to change “traditional” French syntax and grammar structures that place the “masculine over the feminine,” and to create feminine alternatives to any exclusively masculine gendered job titles. The basis of these advocates’ argument is that these linguistic forms of gendered hierarchy contribute to the social sexism and bias against women that France still grapples with today.

Though language alone cannot unravel social structures of oppression like sexism by itself, it is important for a society’s language to represent all its speakers. This representation helps avoid sustained implicit biases against women, which have not only grammatical but social consequences. Mots-Clés, a pro-inclusive writing organization, completed a study where they noted that when “neutral” masculine terms, like “auteur” (masc. of author), were employed in a sentence, participants related the phrase back to men more than women, thus erasing women from the social narrative. The High Council of Equality Between Women and Men (HCE), warns against this kind of continued bias perpetuated through language. They claim that if the language is not watched with “continued vigilance,” these biases will continue to reproduce, “sometimes unconsciously.”

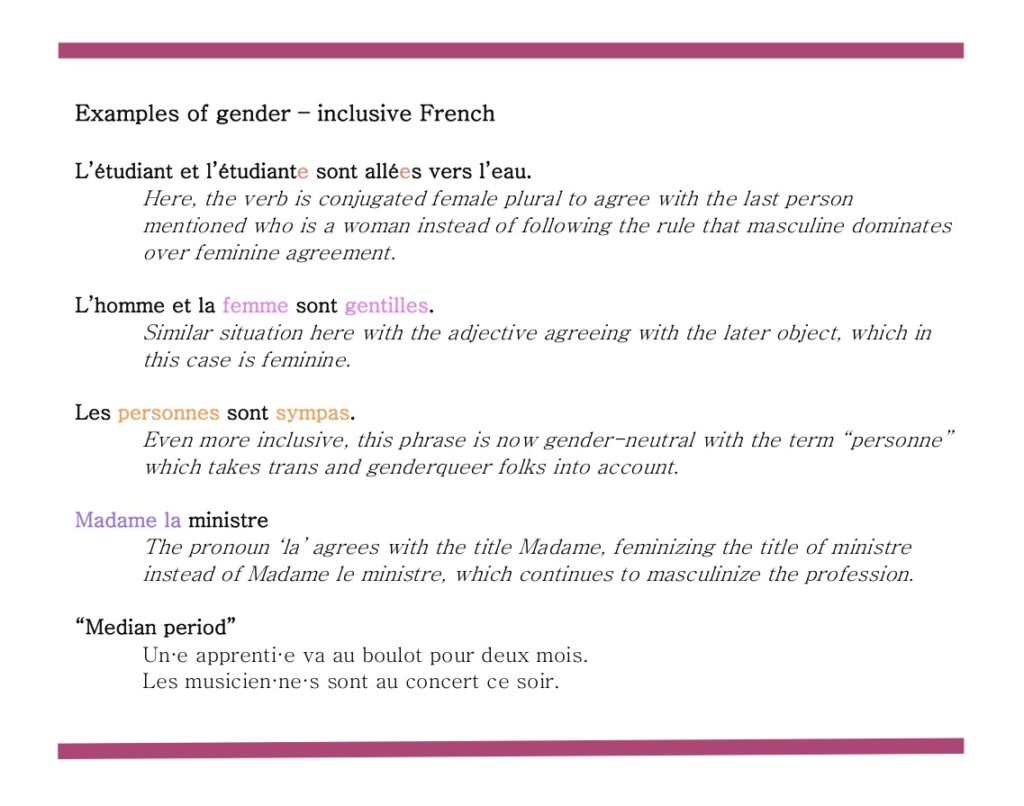

The goal of this movement towards inclusivity is to change several aspects of French syntax and grammar. Namely, gender-inclusive writing focuses on object agreements, the order of gender references (for instance writing women and men instead of men and women), the use of gender-neutral language like “personnes” instead of “hommes et femmes,” or including both sexes in job titles or addresses. You could do this by either writing both options or by using the “median point.

Some linguists suggest that the language isn’t to blame for France’s sexism and changing it isn’t the answer to the social issue. This is due to the conviction that the language is by default “neutral” in its grammar rules and agreements. Others want to leave the language alone and let it run its natural course, which they believe is divorced from social ideology and thought.

Yet social ideology was without a doubt involved in crafting today’s “neutral” grammar rules. It was Claude Favre de Vaugela, a member of the new, post-Renaissance Académie française, who created the grammar rule in 1647 that the “masculine dominated over the feminine” simply because the masculine was the more “noble” gender. One century later, the rule was upheld by linguist and Académie member, Nicolas Beauzée, who validated the grammar rule because of natural “male superiority over females.”

During the French Revolution, a second wave of linguistic changes were applied. As women were vying for their civic voting rights, they also pushed to diminish the use of the masculine grammar rule in French, which was based on assumed male superiority. The backlash was swift. In 1882, public schools were suddenly required to teach the grammar rule of “masculine over the feminine.”

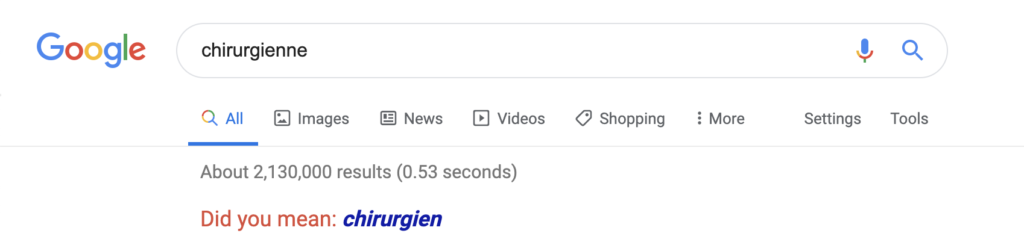

Older, feminized French job titles also slowly disappeared during this time, and a certain linguistic socio-economic hierarchy emerged from the erasure of job titles that applied to women in higher paid and more socially prestigious positions like “doctoresse.” “Patissier,” and other service jobs, such as “serveur,” retained their female equivalent. This hierarchy of work, upheld by placing women’s visibility in the working world within the confines of service to others, keeps women in lower social and economic positions linguistically and perpetuates stereotypes about what kinds of careers a woman should or can have. To see the effects of this in action, try Google searching “chirurgienne” (the female equivalent to surgeon) and you’ll come up null.

As a body that wants to preserve the French language from outside influence yet has a history of implementing its own ideologically driven control, the Académie française presents an interesting contradiction. Currently, the institution — which has few linguists, women, or people of color — prescribes rules for the French language, determines which changes should be made to the language, and which words to include in their prestigious dictionary. The Académie française finds itself alienated from contemporary French while being the one to police the evolution of the language — a contradiction that doesn’t seem to comply with the ideology of letting language run its “natural” course.

Frustrated with the resistance from the government and the Académie, some advocates for the movement are taking things into their own hands. In 2017, Editions Hatier released an inclusive children’s textbook. Mots-Clés and the HCE both created guides to gender-inclusive French that are easily accessible online. In the spring of 2017, more than 300 teachers refused to teach the agreement rule that “masculine takes precedence over the feminine.”

Language cannot change social ideas about gender alone and must be accompanied by social change as well. In a 2018 study by Heather Burnett and Olivier Bonami on inclusive language in the French parliament, the two linguists found that in 1986, when Prime Minister Fabius tried to implement gender-inclusive titles to parliament, a movement spearheaded by Yvette Roudy, France’s first Minister of Women’s Rights, he failed to do so effectively because of the lack of female representation in parliament at the time. However, the study found that in 1998, when Prime Minister Jospin issued a statement mandating gender-inclusive language, he had much more success because of the social visibility (even though small) of women in parliament at the time.

Considering how much controversy clouds the gender-inclusive debate, it is no wonder gender-neutral language hasn’t gotten much traction yet. Some gender-inclusive writing operates as gender-neutral, like the suggestion to use “personnes” instead of the binary option of “hommes et femmes.” But transgender and nonbinary activists are rightfully pushing for full recognition in their language, even making their own gender-neutral guides accessible. The creation of a gender-neutral French language is critical for trans peoples’ everyday life in addition to the fact all French people should have the right to be represented in their language.

Language holds power — if it didn’t, an institutionalized academy wouldn’t have been created to “protect” it from outside sources. Representation is critical in shaping people’s ideas about the world and those who occupy it, and these linguistic representations both impact and are informed by the social and cultural sphere. The question French-speakers must now ask themselves is if they want to continue the narrative of speaking a falsely “neutral” French rooted in sexism, or if they want to include those who bear the consequences of being linguistically and socially marginalized.