I moved back to Paris in September, 2019. I’d lived in Paris for long periods before, in different places, and this time I finally seemed to get the location just right. I rented an apartment with its own tiny private courtyard on rue des Carmes in the Quartier Latin. It was close to the Jardin Luxembourg, a 5-minute walk to the Seine, and a short block from Place Maubert, where, thrice weekly, an outdoor market provided every possible variation of olive, artisanal cheeses, organic vegetables in season and still quivering seafood; once a month there was a bric-a-brac antique market. I got a library card to the vast reading room, an iron-supported structure the size of a 19th century railway terminus, in the Bibliothèque Sainte–Geneviève, the Sorbonne’s impressive library on the Place du Panthéon. I walked miles in the Luxembourg Gardens every day and spent an hour or so every afternoon, across the street, in my decades-long favorite café, Le Rostand, where I’d sat and dreamed and written parts of several books over many years. In short, I was close to everything; the best of Paris was at my doorstep.

Then, at midday on March 17th, 2020, six months after my arrival, France went into its first nationwide Covid lockdown—le confinement. All of the above—everything you go to Paris for—closed.

Strict rules were enforced. You could leave home only for essential errands: food, pharmacies, to see a doctor, and for a single brief period of daily exercise. Traveling beyond one kilometer from where you lived was permitted only for exceptional reasons. You had to print and carry with you, for each sortie, an attestation: a downloaded printed document (later a pdf on your phone) giving your name, address, age, time and reason for leaving home. Masked bands of pumped-up gendarmes, les flics, roamed the streets spot-checking papers, questioning the validity of excursions, and issuing fines for infractions.

I was particularly distressed by the fermeture of my beloved Jardin Luxembourg. I relied on this gem of public greenery for the balance of my psyche. Since I sit indoors much of the day writing, I need to get out regularly and often. My 3-mile early morning circuits of the interior of the gardens were a daily practice—a meditation. I went back again many times a day to sit and think, to look at the endless parade of people, sometimes to write or read on a chair beneath a splendid chestnut tree. For me, Le Luco, as the natives call it, is an essential feature of Paris. Hemingway, of course, came here often, lived in numerous nearby apartments; Gertrude Stein lived and hosted her famous salon a few hundred yards away on rue de Fleurus. The American, Sylvia Beach opened her iconic bookstore Shakespeare and Company a short stroll down the rue de l’Odéon. And countless American writers lived as I was living now in the streets around the Jardin Luxembourg and also came here daily. American literary history was made in that small quartier. All this underscored my sense of place and identity as an American writer in Paris. To be suddenly barred from the garden was a cruel irony.

My small apartment was charming, and, at first, I tried to embrace it to the fullest by reading Voyage Around My Room, by the French Aristocrat Xavier de Maistre who, in 1790, while serving in the Piedmontese army, was punished for dueling and sentenced to house arrest for forty-two days. “Heading north from my armchair, we discover my bed, which sits at the back of the room and creates a most agreeable perspective…” An amusing read but I soon realized that I lacked his esprit de l’aventure micro.

Exceptions to the one-kilometer rule were errands of support or necessity: to minister aid or shop for people who were incapacitated and needed assistance. A friend of mine, a woman who had recently lost her husband, became morbidly fearful of shopping, despite an abundant layering of masks. So, partly for an excuse to get out, I happily shopped for her several times a week for more than two months, going far afield for her exacting requirements available only at her approved herboristes and organic vendors—you learn a lot about someone when you shop for their daily intake (three avocados a day? And the only acceptable coffee is ground by a merchant in a distant arrondissement?). Her list, as esoteric as it seemed, emboldened me to search farther afield for my own necessities. Under these pretexts, I walked many kilometers across Paris, a masked flâneur—“a literary type from 19th-century France, essential to any picture of the streets of Paris… the man of leisure, the idler, the urban explorer, the connoisseur of the street,” says Wikipedia. Oui, c’est moi.

My illicit excursions (“Your papers, please”) reminded me of the French experience of life under the German occupation in World War II. However, les flics made ineffective Nazis and I was able to squeeze a frisson of fun out of my shopping excursions. But I needed more. I needed France.

Eventually, armed with attestations to render aid to challenged friends, or secure a rare medication, I began to take trains (public transportation continued to run) to beautiful old provincial towns, 10 and 20 kilometers outside of Paris, bordering the Seine.

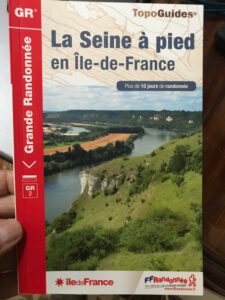

Exiting the stations, I usually headed for the river and, guided by the well-described walks in the Guide Randonnee No. 2, La Seine à Pied, walked 10-15 kilometers toward another train or RER station that would return me to the city. I wore my beret as a disguise (though French men have largely stopped wearing them, and it probably more easily marked me as an American tourist), walked purposefully as if bent on some vital errand, and hoped that I mingled invisibly among the natives shopping or taking the air within a kilometer of home.

These outlying towns and riverside paths—former barge towpaths, now dedicated and well-maintained walking trails alongside the river—were thinly trafficked. My first outing—an exploratory short ride by RER train—took me to Chatou and the Île des Impressionistes, where 19th century daytrippers came from the city to row boats and eat Sunday lunch at the Maison Fournaise, the boathouse café and site of Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s famous painting Luncheon of the Boating Party. It was still there but, like everything else, it was closed. I was entirely alone and it was raining. I raised my phone to photograph a small billboard of the painting erected on the spot where Renoir made his sketches. I had brought my own lunch, a baguette filled with paté de compagne and a bottle of Perrier, which I ate and drank standing under the dripping eaves of the once jolly, sunsplashed boathouse.

A few weeks later, I rode again to Chatou to continue downstream along the Chemin des Peintres, a path lined with more small weatherproofed billboard representations of paintings by Pissarro, Marquet and Daubigny, showing their riverscapes from the positions where they had sketched or painted en pleine aire their famous paintings. Farther along, I passed through Conflans Ste-Honorine, the confluence of the Oise and the Seine rivers.

This was and remains a center of waterway navigation, the shore lined with barges. But the riverbanks on both sides of the town are lined with a Proustian vision: the splendid and renovated 19th-century weekend villas of the bourgeoisie.

Another illicit voyage took me south, where the Seine has a less commercial flavor, to the small village of Cesson. I walked the GR2 path across farmland until I reached the river at the lovely small town of Seine-Port where the Sunday puces, or flea market, was apparently still in full, if masked, swing. From here, the path rose through woods high above the Seine, crossed the river at the turbulent écluse (lock) du Plessis-Chênet where I caught the RER train back to the Gare d’Austerlitz. And then walked my allotted kilometer home.

I made many such little escapes, weekends and weekdays, whenever the urge was upon me. Heading into the French countryside, especially by fast train, is a great joy at any time, and I discovered gorgeous, unspoiled, readily accessible pockets of an older, less tourist-infested France that I might never have found or explored if the more obvious delights had been available.

Fortunately I was never stopped and asked to produce my papers on these far-flung outings. I was knowingly breaking the law, which the French are good about observing. Fines for such flagrant disobedience would have been hundreds of euros. Some of my friends were quite disapproving when I enthused about my flouting of the social contract. But maybe it was my manifest American DNA. We are the people who light out for the territory when anyone tries to civilize us. And during le confinement, for me, it felt like survival.

Peter Nichols is the author of 6 books of fiction and nonfiction, including the bestsellers, The Rocks and A Voyage for Madmen. He lives in Maine.