This week, when I learned that Jean-Luc Godard had died at the age of 91 by assisted suicide, I spent a lot of time reading about the “enfant terrible of French cinema,” watching clips of his movies and thinking about what they meant to me.

Over the course of his 50-year career, the legendary French-Swiss filmmaker, screenwriter, and critic made at least 45 feature films and became known as one of the world’s greatest directors—many would say the greatest—and certainly one of the most influential. He grew to global acclaim as one of the pioneers, along with his friends and colleagues at the renowned film journal, Cahiers du Cinema—François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, and Éric Rohmer—of the French New Wave, the film movement that began in the late 1950s and rejected traditional French filmmaking conventions in favor of a freewheeling spirit of experimentation and self-expression.

Taking inspiration from such filmmakers as Jean Renoir, the Italian Neorealists, and especially American directors like Orson Welles, John Ford, and Alfred Hitchcock, La Nouvelle Vague expanded to include such like-minded directors as Agnès Varda, Jacques Démy, and Chris Marker. Godard survived all the other directors of the New Wave. But their collective work shook up the film world and influenced all cinema that came in their wake, changing forever the idea of what a movie could be.

I don’t remember when I saw my first Godard film. Maybe in the one film class I took in college, or one of many afternoons holed up in a Latin Quarter movie theater when I lived in Paris for two years after graduation. Quite possibly, it wasn’t until I audited a class on the French New Wave when I was in grad school at NYU. That’s certainly when I fell in love; I devoured the entire New Wave section at Kim’s Video on Bleecker Street.

In New York in my 20s, I became obsessed with the whole movie-crazed New Wave band of outsiders, but it was Godard who seized control of my newbie cinephile brain and smacked it around like a cat playing with a mouse. He was the director, more than any other, who showed me that cinema was art and that sometimes the art of cinema required some sweat.

A Godard film could make me laugh out loud and sometimes jump out of my seat—so bowled over, stunned or delighted I couldn’t sit still—and lie awake playing it over in my head, trying to understand what the hell had just happened. Godard was an iconoclast, a provocateur, his films groundbreaking, radical, subversive, brilliant. They sometimes make your brain hurt. He spoke a cinematic language like no other, and his films often left me stumped until I’d thought or talked or written about them. Often, I had to watch them again. Godard loved to break the rules and burn cinematic conventions to the ground. He famously said, “A film consists of a beginning, a middle and an end, though not necessarily in that order.”

When the Academy of Motion Pictures gave Godard an honorary Oscar in 2010, screenwriter and director Phil Robinson said of the recipient (who didn’t show up to collect his award), “He didn’t just break the rules, he ran them over with a stolen car and then threw it in reverse to make sure they were dead.” Godard played with structure, text and narration and played off the American genre movies he loved, turning them into something new that no one could have imagined. The cool bad boy of cinema with thick glasses and a cigar influenced pretty much everything that came after him. Indeed, he was a horizon line on the wide expanse of cinema; there were movies before Godard—and movies after. Quentin Tarantino even named his production company “A Band Apart” after Godard’s 1964 film (Band of Outsiders in English).

Announcing Godard’s death, French president Emmanuel Macron wrote on social media that France had lost a “national treasure.” He went on to call him, “the most iconoclastic of New Wave filmmakers.”

Godard used a loose handheld camera, jarring jump cuts and characters directly addressing the camera not just for style’s sake, but to disrupt the narrative, reminding us over and over that This is not reality. We are watching a movie. He famously said, “Photography is truth. The cinema is truth 24 times per second.”

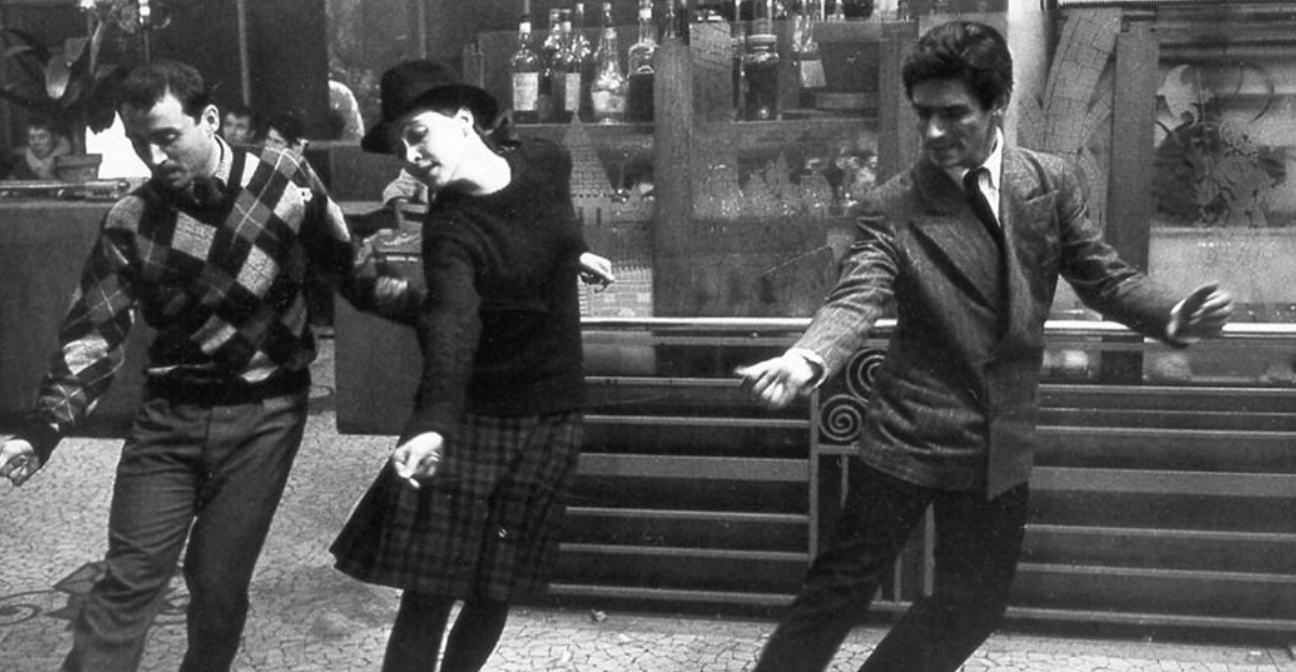

Godard’s death was a gut punch. The man was 91, he’d accomplished so much in his 50-year career, and he’d become famously isolated and cantankerous, but still—a world without Godard? When I told my 14-year-old son, I got choked up and explained to him that we’d lost a legendary director today, whose work changed movies forever. I showed him the dance scene from Bande à part, then a YouTube version I love set to the Nouvelle Vague song Dance with Me. He’d seen it before. I’d shown it to him, of course. I danced along with the characters and found joy where there had been sadness. Next, I’ll show my kid Breathless, the master’s first and most accessible feature film, watching him, no doubt, the whole time for signs of delight and awe on his face. I won’t be disappointed if he doesn’t get it yet. You have to be ready for Godard. His movies demand to be shared, to be lovingly passed along. I don’t claim to have the answers to the questions he’ll undoubtedly ask, but I look forward to the conversations.

Stream some of JLG’s best now. Here are some recommendations.

Breathless (À Bout de Souffle), 1960

Godard once said, “All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun,” but he was being cheeky. The movie that woke the world up to the mad genius of JLG is so much more. His first feature follows a small-time thief (Jean-Paul Belmondo) who thinks he’s a character from a Humphrey Bogart movie and falls for an American student (Jean Seberg). The movie is as much about style as story. This was the first time anyone had seen the overwhelming cool that was Jean-Luc, auteur, with its propulsive rhythm and jump cuts, its visceral beauty and crazy-romantic hotel scene—the slap, teddy bear, flirtation and promises—that goes on and on, making us swoon, hold our breath, and wonder how we lived without this movie all our lives.

Stream it on HBO Max, Criterion or Kanopy; rent or buy it on Amazon Prime, Apple TV, Google Play, YouTube or Vudu.

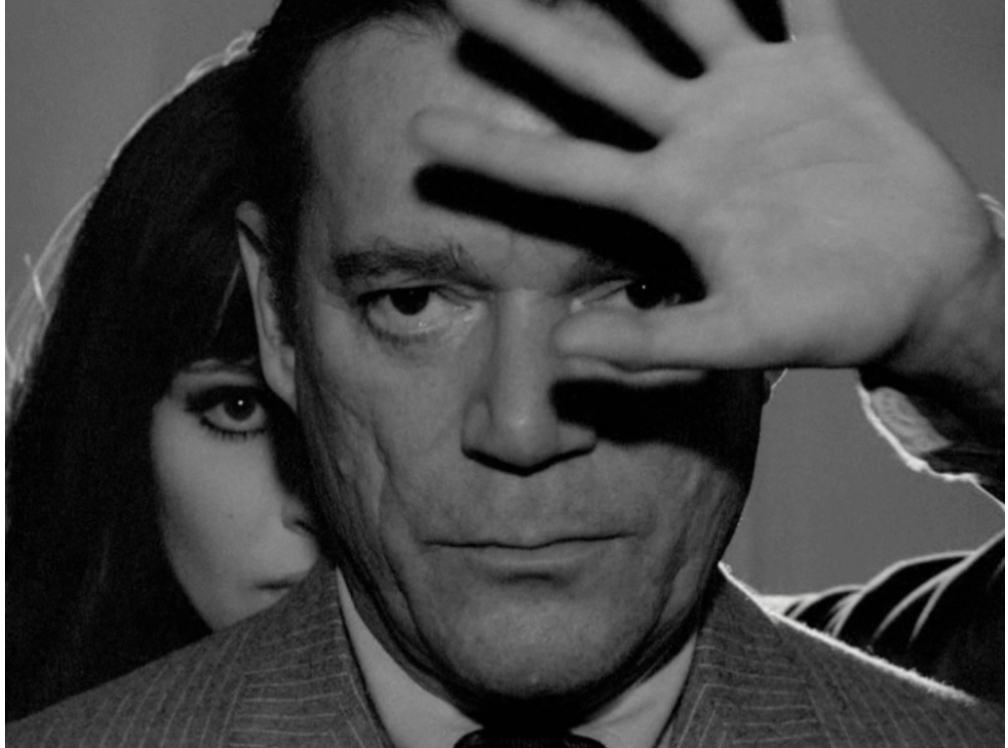

Contempt (Le Mépris), 1963

With Brigitte Bardot as his leading lady and a stunning Italian location, this big-budget adaptation of Alberto Moravia’s novel was the closest Godard ever got to making a Hollywood epic. But it’s all Godard. It’s the story of a disillusioned screenwriter (Michel Piccoli) hired by a pompous American producer, played by Jack Palance, to punch up the script for a version of The Odyssey being shot in Capri by renowned Austrian director, Fritz Lang, who plays himself. Reportedly, part of the deal was to include nude shots of the famously beautiful Bardot. Godard took the piss, inserting random shots of her bare booty and building scenes around the exhibition of her lovely body parts in a decidedly unsexy way. Godard focuses his lens on the tension between the real and cinematic, the result a charged, emotionally complex masterpiece about love in the face of the artist’s struggle.

Stream on Criterion. Rent or buy on Apple+ or Amazon Prime.

Band of Outsiders (Bande à Part), 1964

In the mid-1960’s, JLG made a series of popular, critically acclaimed movies in quick succession. All feature his signature style and distancing techniques, while the director continued to grow and experiment. Again focusing on attractive young people pretending to be gangsters, the film stars Anna Karina (Godard’s wife from 1961-1965) as Odile, a student who convinces her friends Franz (Sami Frey) and Arthur (Claude Brasseur) to help her steal a pile of cash from her aunt in the suburbs. But really it’s all about Paris in black and white—and that dance scene.

Stream it on Criterion; buy on Amazon.

Pierrot le Fou, 1965

Jean-Paul Belmondo teams up with Godard again to play Ferdinand, an unhappily married man who runs away with his ex-girlfriend (Anna Karina), leaving his wife and kids behind. They go on a crime spree through the French countryside, pursued along the way by les flics and a team of hitmen from Algeria. Christian Blauvelt of indieWIRE calls the film, “one of the most beautiful works of art of the 20th century.” He goes on to say, “Anyone who has ever thought Godard’s movies are cold intellectual exercises needs to watch Pierrot le fou. He never made a more romantic movie or a more sensual one.”

Rent on Amazon Prime, Apple TV, YouTube, Google Play, or Vudu.

Alphaville, 1965

For this dystopian science-fiction neo-noir picture, Godard cast expat American actor Eddie Constantine to play secret agent Lemmy Caution, a character he’d played before. Rather than building a dystopian soundstage, the film was shot in black and white against a backdrop of 1960s Paris. Anna Karina helps Lemmy take down an oppressive dictatorship powered by an evil computer that has done away with free thought and emotion.

Stream it on Kanopy or rent it on Apple TV, Amazon Prime, Google Play, Vudu or YouTube.

Masculin, Feminin, 1966

François Truffaut regular Jean-Pierre Léaud plays Paul, a romantic idealist who falls hard for aspiring teen pop star Madeleine (Chantal Goya) in a portrait of a simmering Paris on the verge of revolution. Struggling to find himself and understand the world around him, he quits his job at a magazine to become a pollster. Interspersed with the story of young love are politically-motivated acts of violence, protest, and civic unrest, plus vérité-style interviews with the characters. Godard famously called Paul’s generation “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola.”

Stream on Criterion, HBOMax, YouTube.

2 or 3 Things I Know About Her (2 ou 3 Choses que je sais d’elle) , 1967

In a film that breaks completely with traditional narrative structure, Godard digs into the perils of consumerism in this story of 24 hours in the life of Juliette Jeanson (Marina Vlady), a bourgeois wife and mother who’s works as a prostitute to maintain her family’s high standard of living. Godard narrates the film himself. Both politically and stylistically radical, the film is considered one of the director’s strongest.

Stream on Criterion, HBOMax, Kanopy, Mubi, AppleTV.

Weekend, 1967

The pitch-black comedy stars Mireille Darc and Jean Yanne as a bourgeois couple who literally want to kill each other. They drive to the country to grab a piece of her dying father’s fortune and the trip turns into a nightmare. The centerpiece is a horrendously violent traffic jam that brings out the worst in everyone and allows Godard to flex his social commentary and comedy muscles.

Stream it on HBOMax or Criterion.

Goodbye to Language (Adieu au Langage), 2014

Godard’s 42nd feature premiered and won the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival. Shot in 3D, the experimental narrative offers what Variety‘s Scott Foundas called “a characteristically vigorous, playful, mordant commentary on everything from the state of movies to the state of the world.” It also stars Godard’s dog, Miéville. New York Times critic Manohla Dargis called the film “deeply, excitingly challenging” and “a thrilling cinematic experience that nearly levitated the packed 2,300-seat Lumière theater [in Cannes], turning just another screening into a real happening.”

Stream it on Kanopy or Plex; rent it on Apple TV, Google Play, YouTube, or Kino.

Andrea Meyer has written creative treatments for commercial directors, a sex & the movies column for IFC, and a horror screenplay for MGM. Her first novel, Room for Love (St. Martin’s Press) is a romantic comedy based on an article she wrote for the New York Post, for which she pretended to look for a roommate as a ploy to meet men. A long-time film and entertainment journalist and former indieWIRE editor, Andrea has interviewed more actors and directors than she can remember. Her articles and essays have appeared in such publications as Elle, Glamour, Variety, and the Boston Globe.