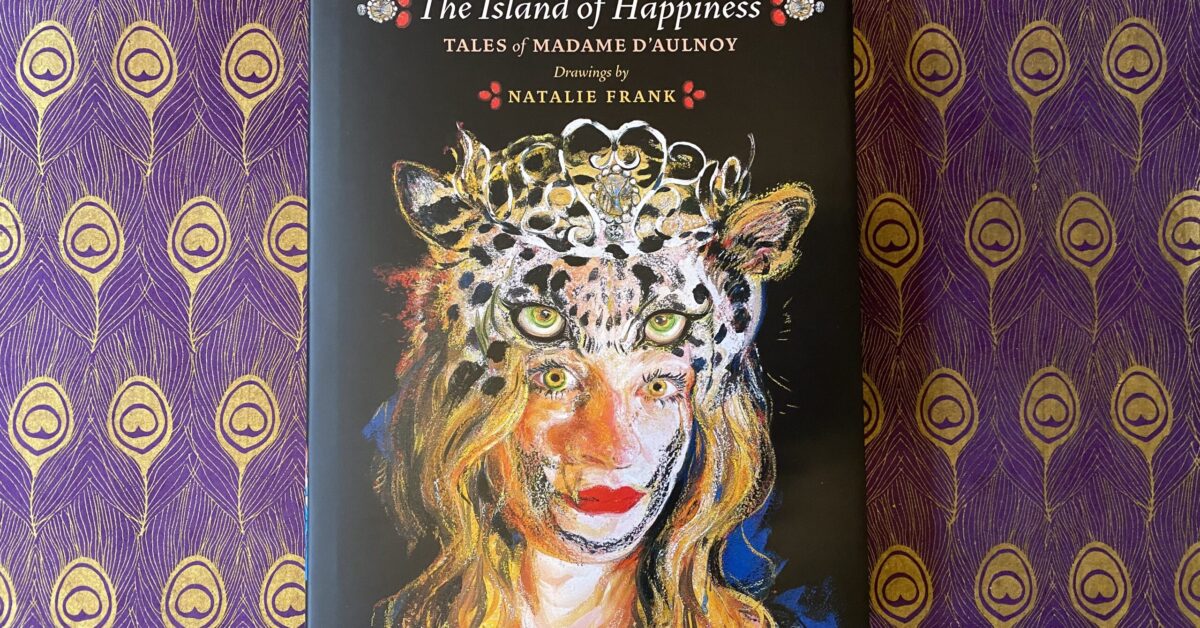

The name of Madame d’Aulnoy may have never passed your ears, but you’ve definitely heard of her invention: a little thing called the fairy tale. This 17th century Parisian noblewoman actually coined the term, conte des fées. And a new English translation of her stories, titled The Island of Happiness: Tales of Madame d’Aulnoy, is a great place to start familiarizing yourself with her best works.

Translated by Jack Zipes and illustrated by Natalie Frank, this beautiful collection both gives new life to these original fairy tales and contextualizes them within the sociopolitical framework of their time.

“What interested her most of all was the status of women, the power of love, ethical behavior, and the tender relations between lovers,” explains Zipes in the introduction. Madame d’Aulnoy was a harsh and absolute judge of morals, as can be seen in the punishments of her characters when they allow their flaws to get in the way of love and justice. She used fairy tales as a means of social commentary during the tumultuous reign of King Louis XIV, which was characterized by excess and “enlightened” hedonism. “Given these dark times, and the censorship that prohibited writers from criticizing Louis XIV directly, the fairy tale became a means to vent criticism and at the same time to project hope for a better world.”

These stories helped kick off the popularity of the “literary fairy tale” in late-seventeenth century France, with stories borrowed from folk tales and adapted to the upper classes, oral histories going back and forth up and down the class ladder, evolving each time. The main contribution d’Aulnoy made to these tales, aside from refining and repackaging them for the salon set, was to put fairies front and center, taking the place of gods and goddesses who wielded arbitrary judgments, and giving powerful women the ultimate moral say-so.

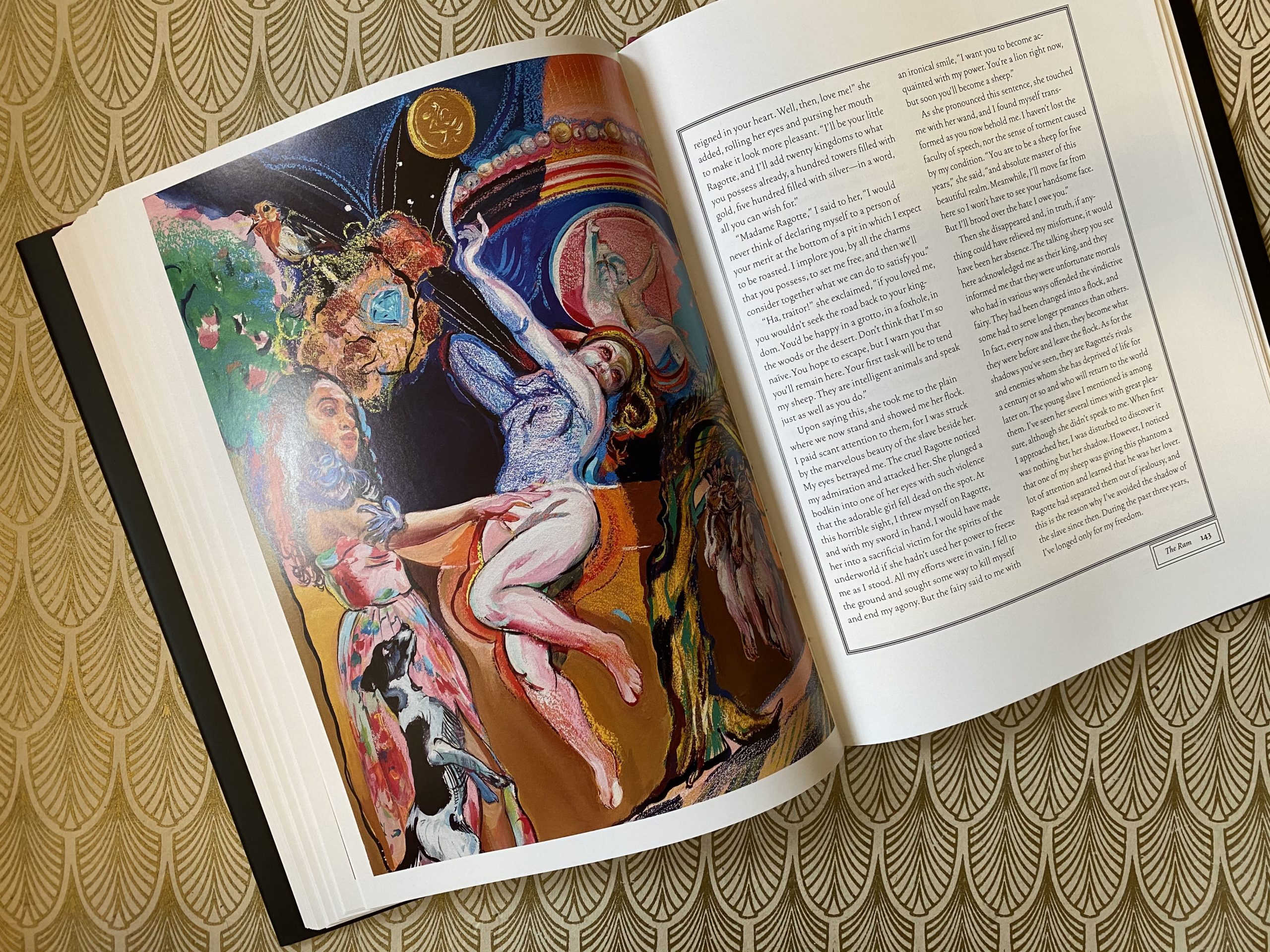

Though the subjects of Madame d’Aulnoy’s stories are nearly always princesses, their noble femininity is often a force for subversion rather than archetype. In “The Tale of Mira,” the titular princess is so beautiful that her disinterest makes men perish, yet when she finally chooses an object of desire, it kills her. It’s a metaphor that rings painfully true even today, as womens’ beauty is often weaponized against them, and their unapologetic desire viewed as justly punishable. In “The Island of Happiness,” another beautiful princess brings her lover into a world of eternal youth and pleasure, only to have him abandon paradise to pursue fame and vainglory.

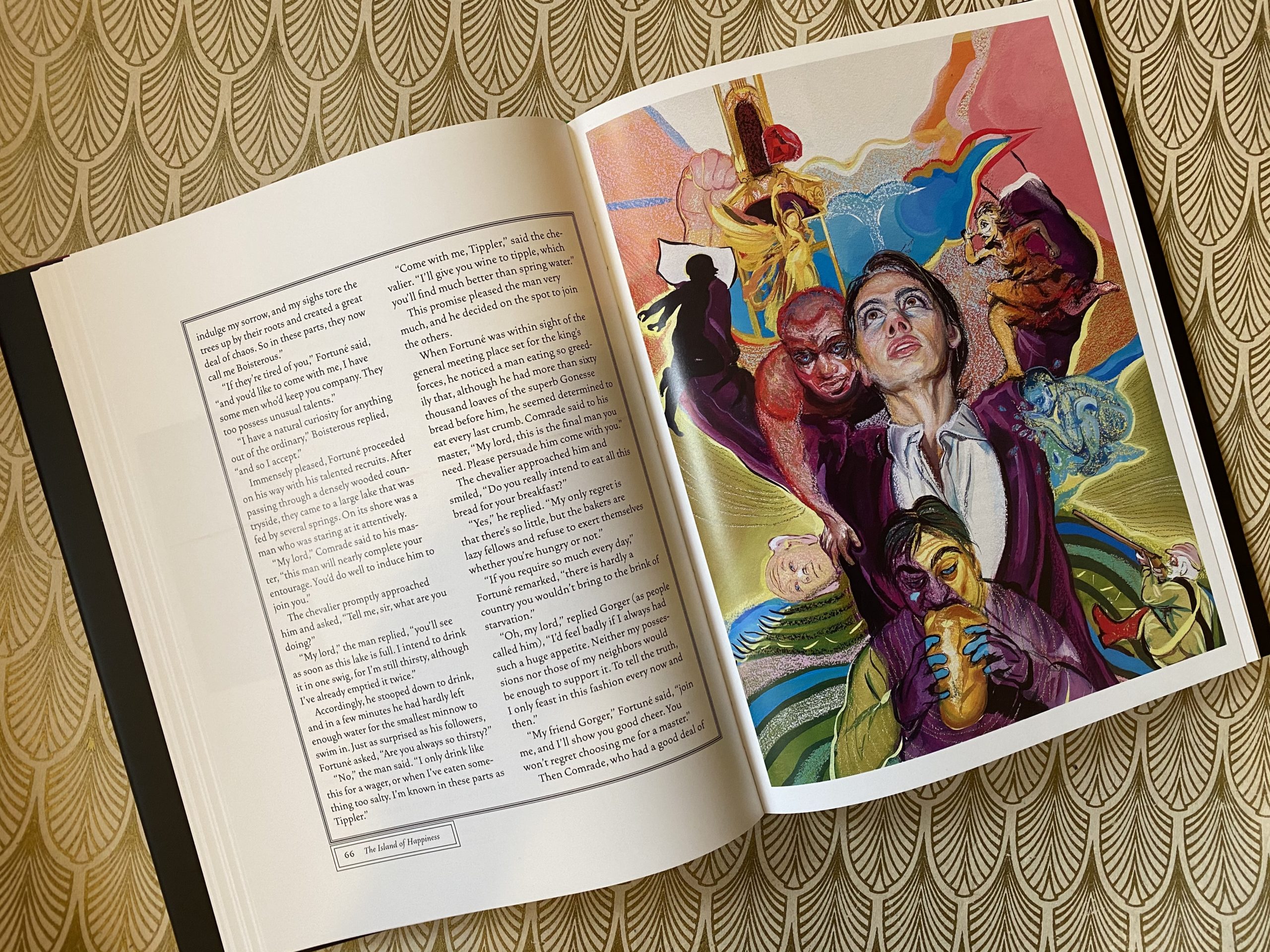

But not all princesses are punished for having a pretty face and a kind heart. “Finette Cendron,” d’Aulnoy’s take on the Cinderella fairy tale, ends with the heroine winning her prince and showing generosity towards her wicked stepsisters. And “Belle-Belle, or the Chevalier Fortuné,” the longest story in the collection, is an epic comedy about a young princess who cross-dresses as a man in order to save her father from military service in a Mulan-esque ploy. When Belle-Belle becomes the Chevalier Fortuné, she is instantly plummeted to high rank because of her physical skills and noble manner, and becomes an object of desire for all women in the court. It can be read many ways by a modern reader—as a queer love story, a literary precedent for non-binary representation, a commentary on how men and women are treated differently even when presenting the same talents and abilities.

“I came to the world of Madame d’Aulnoy because I wanted to draw tales that I read as unequivocally feminist,” Natalie Frank writes about her journey illustrating these tales. “The wily heroines of d’Aulnoy’s stories test the limits of acceptable behavior for women and appropriate roles for female characters in fairy tales… Love and power, intertwined, enable women to seduce, triumph, change form, and tell their own stories.”

It is true that you can’t always judge a 300-year-old story by modern standards, but the brilliance of these stories, as outlined in the introduction, is that they were never meant to be definitive. Fairy tales have always been adapted and retold to fit the class, culture, and morals of the moment. They belong to everyone. If Mira were a 21st century supermodel instead of a 17th century princess, her story would still ring true. If Belle-Belle spurs memories of Mulan and She’s the Man, it’s for a reason. These stories are always in translation. But this one in particular is a pretty good place to start.