The year is 1721. Louis the 15th is the King of France, but is not yet old enough to rule. Paris is dark and overcrowded, with scarce clean water or light. Across the ocean, a smallpox epidemic is leveling Boston. John Hanson, the man who will become the first President of the United States, is born. (Did you think it was Washington? Better look into your history.) The shameful slave trade of Africans is now a hundred years old. Europeans across the New World are encroaching on Native American tribal lands; in the next hundred years, the Native Americans will lose more than two thirds of their land and suffer unbelievable cruelty. Native Americans are being sold into slavery, some overseas. And the colonies need women.

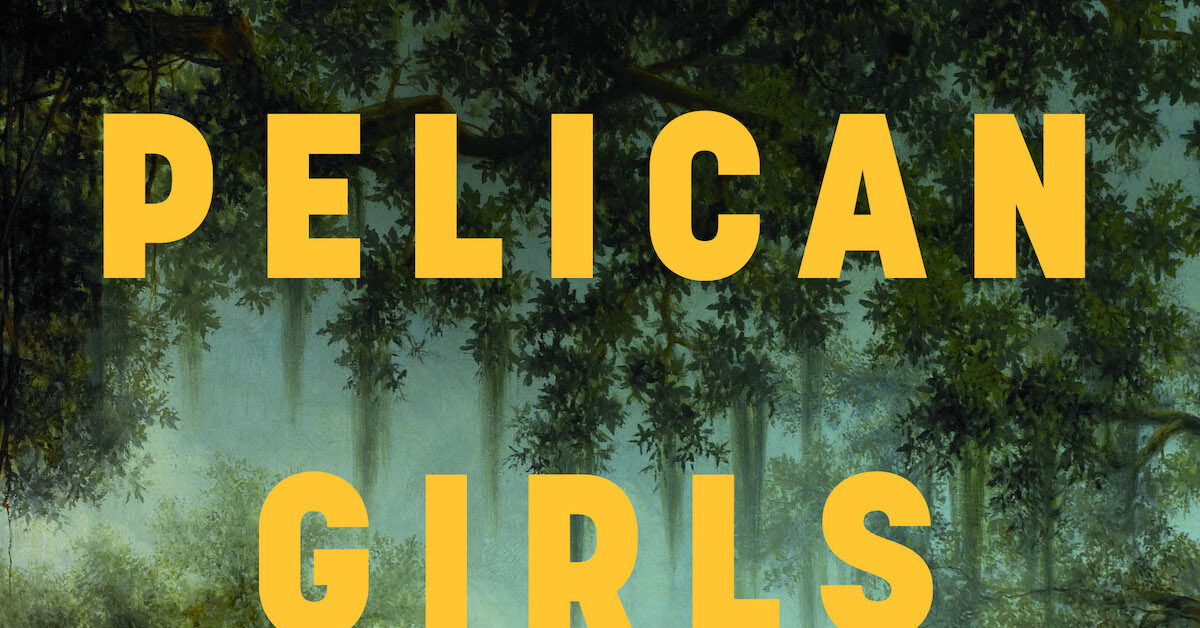

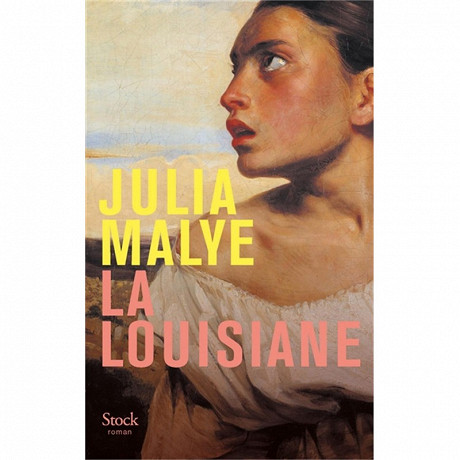

A ship called La Baleine, full of French women, lands on the coast of Louisiana. As La Baleine crossed the Atlantic the women aboard endured rough seas, hunger, a pirate attack, filth, rape, and, for some, death. They are bound for an “extraordinary land that would give you everything you wanted and more,” writes Julia Malye, the author of this engrossing and moving new historical novel, Pelican Girls.

When the women disembark in the shallow waters where the Mississippi meets the ocean, their journey is not yet over. They must travel by canoe into the settlements of La Louisiane, up the river and into the bayou, where they will be chosen by French settlers for wives. But first, they take in the landscape: “Still and flat, like everything that is far–movement wiped out by the distance, trees as blurry as a child’s drawing. They stare as if studying the face of a stranger. They imagined this moment so many times that it feels almost wrong to live it. What is there to look forward to, now that they’ve crossed the Atlantic?”

That essential question rings in the mind of this reader: What in the world can these women look forward to? (Or, to put a finer point on it, what in the world should they know to fear?) These girls and women have signed up to leave a Paris “hospital,” which houses orphans, criminals, those deemed mentally ill, and others disowned by their families. They are hoping for something of a new start–what that will be, and how they will get to that fresh start is completely unknowable. No one tells them what is coming, no one helps them. They must live it, moment to moment, with nothing to prepare them for this brave new world. In the process, they endure incredible trauma–trauma these women are, courageously, attempting to overcome within one generation, as if their bodies can endure as much as possible, hold onto it, soak it in, but never let it seep out. In the process, the women experience a depth of connection that is life saving and extraordinarily moving.

In this 346-page, densely written book, we cover 14 years, with very little back story. Relationships that began on the ship, between Geneviève, Pétronille, Charlotte, and Étiennette, become central. Their experience together on the boat binds them through much of the book, even when their lives pull them apart. As Malye writes, “On La Baleine they were all equal. But once the women were married, Étiennette started paying attention to the husbands’ positions. The unlucky ones, those who were married off to starving farmers, suspected criminals, or destitute cadets, were never invited to her home. That in itself had been disturbing. The men changed the way they saw themselves, each other–what the women wanted and hoped for, what they felt they deserved.”

As the novel goes on, the central relationship becomes that of Geneviève and Charlotte. Geneviève has been in jail in Paris for performing abortions illegally. Charlotte is an orphan. In the New World, we follow them through marriages to strangers, attempts to have children, the dangers of childbirth, physical and psychic abuse, through poverty, and, for a short time, through life in a convent together. But ever-present are the muddy bayous, the tangled trees, the incredible storms that demolish everything in sight, the incessant mosquitoes… not to mention the painful slavery of Africans, brought to work the plantations, and the French disregard for, and then wars with, the Native Americans. Psychic and physical pain are a hallmark of this epic story. But so is love. Indeed, Malye has achieved some of the most nuanced and beautiful writing about women loving women I have ever read. I spent a lot of time thinking about why that was, what was different, why it moved me as deeply as it did. It may be because her writing is devoid of a sexualized gaze that detracts from the deep connection depicted. In the hands of this talented writer, love is only love; it has a purity I don’t know if I’ve ever seen elsewhere.

Though the novel is primarily about the French women we come to know, there is a chapter in the last third of the book about Utu’wv Ecoko’nesel, a Natchez Indian woman whose life becomes, for a short time, intertwined with the French Pétronille. Though there are attempts made to humanize the suffering of the African slaves and also include Native Americans in this narrative, these characters are bystanders to a story that is really about the French women. Lines that humanize the Native women who are at war with the settlers, like “Women crying in their cabins, whether they had loved their husbands or not,” don’t really do the Native story justice. And, unfortunately, the chapter about Utu’wv Ecoko’nesel feels thrown in for convenience; she becomes visible in the narrative only because her life becomes intertwined with a white, French family. I would have liked to have known her from the start, when she was a child growing up in that wild land, learning the plants and trees; what changed when the French colonists arrived, and how it felt as the French encroached further into territory that was not theirs to take.

Malye has published three novels in France and this is her first written in English. At times, despite this pedigree, it can feel like a first novel. The first third of the book is cumbersome, burdened by sentences bursting with descriptors, some of which are tedious or awkward. Too many French words peppered throughout threaten to overstuff the manuscript rather like a foie gras, even to this reader who is proficient in the language. Part of this quality is, in its nature, a French novelist’s heritage. Sentences in French can go on and on, and there isn’t the same historical adherence to the idea that spare language can actually have a fuller impact. At times, that first 150 pages felt like they could have been reduced to a mere prologue and still been wonderful, giving way to the story that springs forth in the middle of the book.

None of these mechanical issues detracted, however, from Pelican Girls (La Louisiane, in French, with foreign rights sold in 25 countries). Particularly in the aforementioned middle of the book, the writing is beautifully rendered and heartbreakingly poignant. Some of the lines will sear through you and leave a scar. Lines like, “Her daughter is obsessed with the kind of tree that was used to make her father’s coffin.” Or, “An imperfect silence sets in; birds can’t refrain from singing.” Or, “How quiet the silkworms turn when there is wood to climb, when there are sweet leaves at the end.” Or, “Geneviève starts mouthing syllables, slowly, the pink of her tongue flashing between the little gap of her front teeth.” Exquisite sentences like these are earned, by both writer and reader, and offer beauty layered like soft silt on top of truth.

If I had to say what this novel is about in one sentence, it’s about love–love between women, who care deeply and tenderly for each other as they go through horrible trials that almost break their bodies and minds. But through it all, they are unfailingly loyal to each other, in a way that, it strikes me, only women can be. If I were greedy, I might also add that it is ultimately a novel about finding home in the most unlikely place, one that, “was once dangerous, a prison of trees, a maze of marshes, an ocean of mud.” But eventually, those women who came with nothing and had nothing to lose, fell in love with the land, and even the hardship. Malye writes that, in their old age, they came to “swear the horizon is wider in La Louisiane” than anywhere else.

Caitlin Shetterly isan Editor at Large of Frenchly. She is also the author of 4 books: Fault Lines, Made for You and Me, Modified, and the novel, Pete and Alice in Maine, which was published in 2023 by Harper. She is a native daughter and she lives with her two sons and husband in an old house on the coast of Maine.