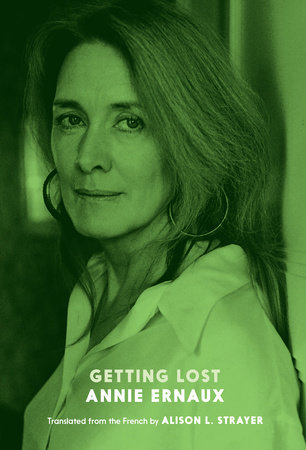

This week’s announcement of Annie Ernaux’s Nobel Prize made me wish that I had not decided to begin her oeuvre with her latest book. Published in English translation just days ago, Getting Lost is less a work of literature than a document: the 20-month diary Ernaux kept while having an affair with a Russian diplomat, when she was 48, and he was 35. As a record of that period, it succeeds. Clearly, she wants to say: This thing happened, and these were my emotions as it happened. She has already said as much in her novel Simple Passion, which covers the same material, and was published in France in 1991. So why, in 2000, after rereading her diary, did she decide to type the book up, and publish it (unedited) in 2001 in France, and then this month in the States?

In her preface to Getting Lost, Ernaux writes, “I perceived there was a ‘truth’ in (the diary) pages that differed from the one to be found in Simple Passion—something raw and dark, without salvation, a kind of oblation. I thought that this, too, should be brought to light.”

She concludes her preface by saying that the man of whom she writes (not named but clearly not too hard for those in her circle to identify) might object to her publishing and claim, “I only saw her to get my rocks off.” That Ernaux suspects he is capable of these words demonstrates how much he still pains her, though twelve years separated the writing from the publishing of her diary.

Though one never questions Ernaux’s passion, the object of her passion does not entice the reader the way he entices Ernaux. He is a Stalinist, anti-Semite, and misogynist, who is not forthcoming about his feelings for Ernaux, if he indeed has them. Ernaux always wonders, constantly on tenterhooks, about when he will call. What else? “He likes fancy cars, luxury, social connections, and isn’t much of an intellectual.” Oh, and he’s married. What he has going for him is that he meets her passion in kind. At least, when they are together.

At the time of the affair (1988 to early 1990), Ernaux was already a famous writer. She believes her lover is interested in her, because of the “glory” that attaches to her name. After the clearly difficult years documented in her earlier books, the Ernaux of Getting Lost is now living a life of privilege. She mentions a dinner with “Charles and Diana.” Even so, the affair so obliterates everything in her life that she spends most of her time simply waiting for the man to call.

Ernaux speaks of love, as she describes the relationship, but she seems more in thrall with being in thrall than engaged with the Russian lover as a person. Her happiness focuses on him arriving and the subsequent lovemaking.

Early on in the diary, she writes, “I make love with the same desire for perfection that I feel in relation to writing.” But what is “perfection” in relation to the sex act?

I don’t know, but I do know that I longed to learn whether she and the Russian diplomat ever had an interesting conversation? Or if they laughed? If so, she never records it. The sex is thrilling. I get that (though perhaps I don’t get how sex can be thrilling in the absence of other ways of connecting, but that says more about my desires than Ernaux’s).

What will be relatable to anyone who has loved and not been loved back (or been loved unclearly or murkily back) is how lousy that feels, how unempowering it is to be with someone who refuses to validate you. Ernaux describes the pain of this in language as fevered as her lovemaking …After running her mouth over her lover, Ernaux writes, “I don’t stand a chance, it’s the road to perdition.”

Ernaux is compelled by being wanted (well, who isn’t?); haunted and troubled by being rejected (ditto).

And yet it is exhausting to read her record this over and over again. The diary gives us her thoughts, her fine sentences, her frankness, and her honesty, without the ruthless selection that allowed her to create a 62-page thoughtful meditation with identical information. At one point in Simple Passion, she writes “Quite often I felt I was living out this passion in the same way I would have written a book: the same determination to get every single scene right, the same minute attention to detail.” A-ha! Now I get the sentiment that so confused me in the diary.

In the end, I found it tormenting (and boring) to read about Ernaux’s torment. The feminist in me does not want to see a woman of Ernaux’s accomplishments feel as she does, though, of course, I’ve seen many an accomplished woman do the same. But it is more than that: “Every woman adores a Fascist,” Sylvia Plath writes in her poem “Daddy.” In love, if not in politics, maybe that’s true for Ernaux who sees the Russian as “that ‘man of my youth,’ blond and unrefined who fills with me pleasure.”

But I could not get past her lover’s Stalinism or anti-Semitism, as she impales herself on the sword of her passion. There’s not one moment in reading the diary when I did not want to shake the 48-year-old Ernaux or the 60-year-old publishing the book in French, or the 82-year-old publishing the book in English translation, and get her to cough out the final line of Sylvia Plath’s famous poem: “You bastard, I’m through.” (And to be fair, she does call the man a bastard toward the end of the diary, but if she was actually through with him, would she find that this old diary of hers still has something to impart?)

Perhaps it sounds like I do not understand senseless passion, and thus the diary. I have certainly been crazily in love with someone who did not love me back. There are men who will never validate. But happily, for Ernaux, there are Nobel Prize committees who will.

Debra Spark’s 11th book, the novel Discipline, will be published in 2024. She teaches at Colby College and in Warren Wilson’s MFA Program for Writers. She co-edited Breaking Bread: Writers from New England on Food, Hunger and Family, which came out in the spring of 2022. She writes a monthly book review column for Frenchly called “Bouquin.” This is her third review.

Photo credits: Oliver Roller, top. Louis-Monier, bottom.