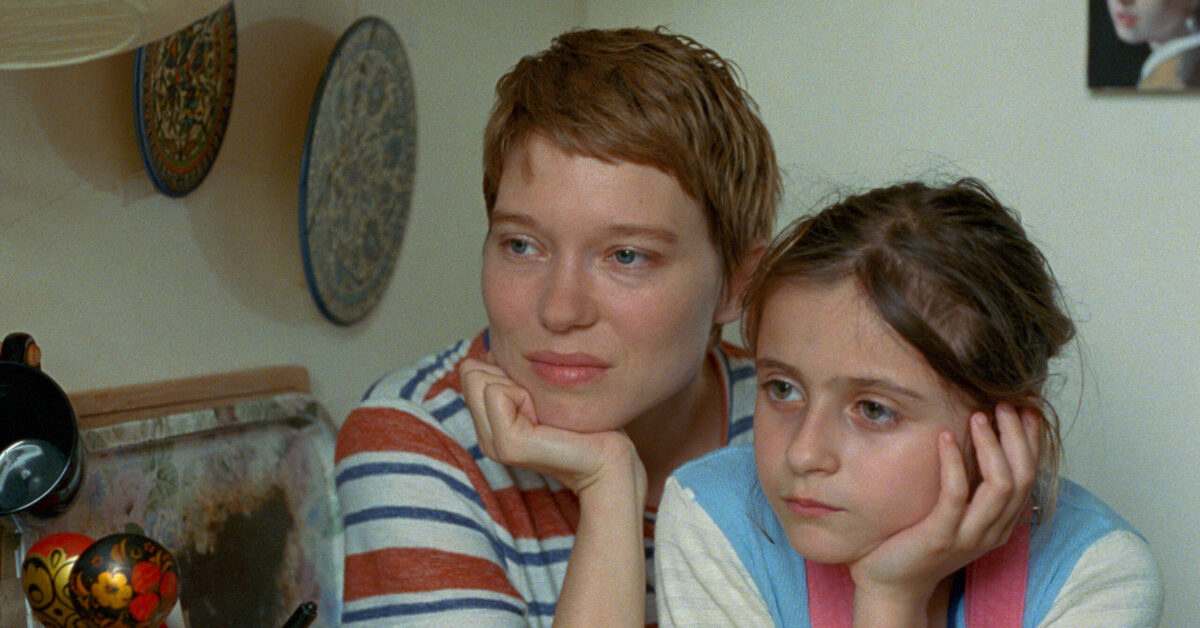

Mia Hansen-Løve’s One Fine Morning packs an emotional wallop. The latest film by the Bergman Island director stars the ubiquitous Léa Seydoux as Sandra, a young widowed mom, whose father is suffering from a neurodegenerative disorder. When she visits him early in the film, he can’t figure out how to open the door. “Where is the …” he asks, unable to find the word. “The key?” she responds. “In the lock.” Without any visible anxiety, she walks him through it. Once inside, we meet him. In a fragile, moving performance by Pascal Greggory (Irma Vep, Pauline à la Plage), her father is charming and intelligent, poetic and sweet, his mind still lively, even as his memory and vision slip away.

The film’s arc follows Sandra as she, her sister (Sarah le Picard) and mother (Nicole Garcia), long divorced from her father, struggle to find him a place to live, since he’s no longer able to care for himself in his Paris apartment. He has a girlfriend he adores, Leila, but with health problems of her own, she isn’t helpful. Meanwhile, Sandra races through her days in sensible jeans and a backpack, darting about in an effort to keep all the moving pieces of her life afloat. She works as an interpreter, drops off and picks up her young daughter, Linn (Camille Leban Martins), takes time to visit her grandmother.

Along the way, she falls in love. At the park with her daughter, Sandra runs into an old friend, Clément (Melvil Poupaud), with his young son. When they get together for a drink, he confesses that his marriage is faltering, and Sandra admits she hasn’t met anyone since her husband’s death and believes her love life is behind her. Having never seen the workplace of a cosmo-chemist (his super-sexy profession) she visits his office, which looks more like the cramped archeology department of an underfunded Parisian lycée than whatever sophisticated space she’d imagined. But it’s there, in this small drab room, that they stumble into the sweetest of first kisses, followed by a blissed-out, almost giggly discussion about pouncing and getting slammed up against walls and who kissed whom first.

In a way this is the story of a woman who needs, and finds, something, someone, to hold onto as her father slips away. But it isn’t as simple as that. There’s such subtlety and humanity in every moment, it’s like watching life unfurl, the life of a woman both bracing herself as her father slowly disappears—and falling in love. The shifts in emotions are subtle—there’s no swooning, no denial, no primal howls at the universe. Sandra simply reaches for the simple pleasures and moments of peace that allow her to remain solidly planted upon the earth. When we meet her, she’s utterly capable, juggling her work and personal life, effortlessly translating presentations from German into French and French into English, running off with her kid’s ice cream cone. She cracks a smile, tells a joke, never seems flustered with her father’s inability to perform simple tasks. When such a levelheaded person suddenly chokes back tears, unable to speak when a former student of her dad’s asks about him, it hits you hard. Who hasn’t been there?

Seydoux’s performance is a revelation for her range and vulnerability. While we’re used to her playing cold, over-the-top, the simmering Bond girl, the object of desire, here she’s a normal person. Her hair is cut unfashionably short. She wears little makeup, if any. Emotions, subtle or transformative, dance over her face—joy, desire, pain—the emotions of a real person going through a period in life when feelings live closer to the surface. She’s more beautiful than ever. With Clément, she’s petulant, possessive, vulnerable. With her father, she’s patient, filling in the blanks when he can’t find the right words.

Sandra’s relationship to her father is achingly beautiful—and complicated. Along with her obvious adoration, she is often hurt by him, largely because of his illness. He tells her there are three people he cares for most: Leila, himself, and… We watch Sandra’s face, anticipating (hoping?) he will name her, but instead he says he can’t remember the third person he loves most. She doesn’t flinch. But other times she does. It’s clear that she yearns for the father he used to be. When clearing out his apartment, her mother wants to get rid of his books, but Sandra believes they contain his spirit. In his notebooks, she finds poignant lines of text that read like the poetry of mental and physical degeneration.

The emotion sneaks up on you. You might convince yourself it’s okay if her relationship with Clément doesn’t work out. This isn’t a romantic comedy, after all. It’s not about the love story. It’s about a woman coping with the loss of her father, the romance her way of getting through it. But you can’t help but yearn for her happiness. She deserves it. You want her to continue smiling the way Clément makes her smile, but you also understand that this is real life. He has a wife and a child. When she says, “Don’t forget me,” when he’s leaving town, her need is palpable. When they take a break so he can sort things out, a text from him—“I’m going crazy without you”—elicits a wave of emotion that is wrenchingly human and recognizable. Even as you understand that it could go either way, you hope desperately that she’ll get the guy. You might even find yourself praying for this woman who has already lost so much. Just let her have this, you might find yourself thinking. Please God, just let her have this.

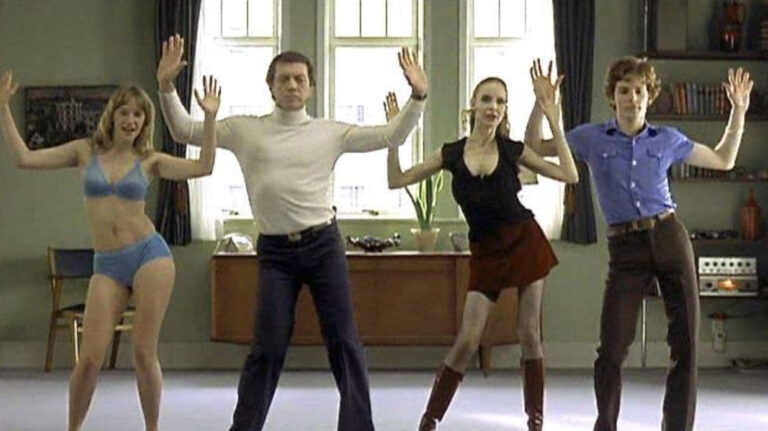

While The Man in the Basement will certainly set your heart pumping, there is nothing subtle or heartwarming about it. Philippe Le Guay’s psychological thriller stars Jérémie Renier (My Way) and Bérénice Bejo (The Artist) as Simon and Hélène Sandberg, a couple who sell their cave (basement) to Jacques Fonzic (François Cluzet), a retired history teacher who plans to use the space for storage following the recent death of his mother. Simon, who is Jewish, and Hélène soon learn not only that Fonzic is living in the basement just a few floors below their home, but also that he was fired from his job for being a Holocaust denier known for his anti-Semitic diatribes. When their attempt to cancel the sale fails, they hire a series of lawyers, each with something to teach them about real estate law and the mind of a conspiracy theorist.

As their attempts to kick him out persist, the unpleasantness and dread escalate. When neighbors and the concierge object to Fonzi’s using les toilettes in the building’s courtyard, Simon padlocks the door. Fonzi starts using the bathroom at the bar down the road, where he calls the bartender a “dirty Arab.” When he can’t make it that far, he defecates in the hallway.

The mood that Le Guay and his cinematographer Guillaume Deffontaines create from the beginning is ominous, suggesting sinister possibilities. With Bruno Coulais’ eerie soundtrack and strong, compelling performances across the board helping build emotion and suspense, the camera leads us portentously down the long dark corridors below the bougie apartment building, rows of ancient wooden doors concealing the caves that hide who knows what.

With the pressure of the various lawsuits ramping up and an ugly stain mushrooming its way across their bathroom ceiling, the Sandbergs’ 16-year-old daughter Justine (Victoria Eber) starts running into Fonzic—in the courtyard, at the burger joint he frequents, at the corner deli, and he gives her the earful that’s become his raison d’être: Fonzic as victim, a man attacked for simply asking questions. The importance of questioning, of refusing to blindly accept the official truth. His right to express himself and defend his freedom of speech. Blah blah blah blah blah. Rhetoric like his dominates our current political climate. And yet, from the mouth of this poor man, who can only afford to live in a basement, who’s handsome and articulate, despite his shabby clothes, this man who’s lost both his mother and, we later learn, his wife, this man who played the adorable paraplegic in Les Intouchables (!), it starts to sound reasonable. Especially to a smart, impressionable 16-year-old girl like Justine, it might just sound like the truth. And that’s when this viewer starts feeling Cape Fear vibes that end up being a red herring, or one potential threat too many.

Of course, Justine’s parents start fighting. Of course, their marriage suffers. Of course, they discuss the history of the apartment, which was originally owned by Simon’s grandfather, then seized during the Occupation, only to be retrieved after the war. Simon’s neighbors will accuse him of not being the rightful owner of his home. He will be called a self-hating Jew by his brother. Hélène, his wife, will come apart at the seams and blame her husband.

It takes the third lawyer, an old grad school friend of Simon’s, to finally bring up the most obvious point: People aren’t allowed to live in caves! Let’s get him for breaking that law. Let’s get a sample of his poop in the hallway! That will totally bring him down. By this point, the escalations come fast and furious. We’re meant to believe that even kind, ordinary people act rashly when pushed to extremes. It’s Simon vs. Fonzic. Moral, upstanding citizen, architect, husband, father, son, brother, Jew with a heart of gold vs. shady old racist Holocaust denier. Guess which one will commit a violent act in defense of all that is precious to him.

Whether or not you think the film is over-the-top or spot on and relevant to our current political moment, you too will breathe a sigh of relief in the end. You too will wince at a final moment of ugliness that signals vindication. A smart move on the part of the director was to build suspense from the start, suggesting the terrifying direction this story could go, giving us access to the inner world of the family whose perfect, unblemished, peaceful lifestyle is at stake, and letting us imagine what it would look like for a madman to snatch it from them.

One Fine Morning opens in New York and Los Angeles on January 27, followed by a national release. The Man in the Basement opens i

Andrea Meyer has written creative treatments for commercial directors, a sex & the movies column for IFC, and a horror screenplay for MGM. Her first novel, Room for Love (St. Martin’s Press) is a romantic comedy based on an article she wrote for the New York Post, for which she pretended to look for a roommate as a ploy to meet men. A long-time film and entertainment journalist and former indieWIRE editor, Andrea has interviewed more actors and directors than she can remember. Her articles and essays have appeared in such publications as Elle, Glamour, Variety, Time Out NY, and the Boston Globe.