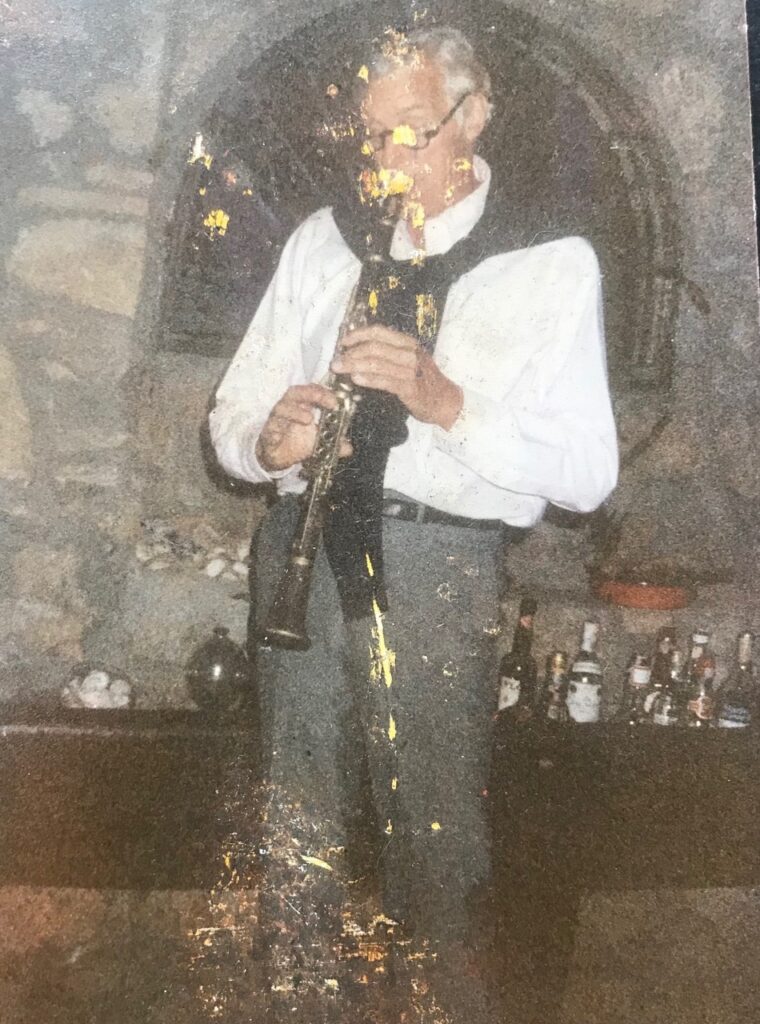

My father played the clarinet. Jazz was the music du jour when he was growing up in the 1930s and 40s. Benny Goodman was his Eric Clapton. He jammed after school and in college with friends who played saxophones, trumpets and trombones. When he was stationed in the Pacific in World War Two, he brought along his clarinet.

After the war, he lived in Greenwich Village, New York. He played his horn in clubs there, with a number of well-known musicians. He told me he’d hoped to be a professional musician, that he thought he might have been good enough if he’d stuck with it. But his father, who worked forty years for a medical instrument manufacturer, told him that few people make a living out of music. Now that the war was over and he’d had some fun, his father told him, it was time to get a job. So my father went into advertising. He became a ‘Mad Man’ in New York.

But he never stopped playing his clarinet. Throughout my childhood, he came home after a day at the office, pulled off his tie, poured himself two fingers of scotch, got out his clarinet, put a record on the Victrola, closed his eyes, raised his eyebrows, and began to blow. His lips and jaw quivered around the reed as he made tremolo effects with a perfect embouchure (the acquired arrangement of lips, mouth and facial muscles to best play a wind instrument—trumpeter Chet Baker had his teeth knocked out in a fight in 1966; his embouchure was ruined until he got dentures). My father played with Benny Goodman. He played with all the musicians he thought he might have played with if he’d stayed in Greenwich Village: Mugsy Spanier, Bix Beiderbecke, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong. He played with them all when he came home after work.

I was a boy when we moved to London and my father took me to see some of his music’s stars when they came to town. I particularly remember a Benny Goodman concert at the Royal Albert Hall on October 2nd 1971.

“That’s Benny Goodman playing there,” my father told me. We had great box seats above the stage. He gazed at Goodman as he might have an old friend; he smiled the most rueful smile I’ve ever seen. Benny Goodman meant nothing to me. “Benny Goodman,” my father said. “One day you can say you saw him play.” I was listening to the Beatles. My father didn’t get the Beatles, but my mother sure did.

Another star in my father’s pantheon of jazz greats was Django Reinhardt, the Romani French jazz guitarist and composer. My father told me that Django was a gypsy; that when Django was growing up he’d lived in a gypsy caravan in the north of Paris, near the flea markets in St. Ouen, and that, when he was 18, his caravan caught fire and Django’s left hand was severely burned and permanently deformed, his ring and little finger bent and useless. This was his fretting hand, the one used to make chords and perform the dexterous finger work on the fretboard. “Listen to this,” said my father, playing me some records. It was after this accident, he told me, that Django learned to play again, with a new fingering style that made him what most professional guitarists and musicians still believe was the greatest jazz guitarist of all time.

Reinhardt developed and popularized a unique brand of jazz, ‘Manouche’, or ‘gypsy swing,’ ‘jazz manouche’ after the Manouche clan of Romani peoples from Central Europe, from whom Reinhardt was descended.

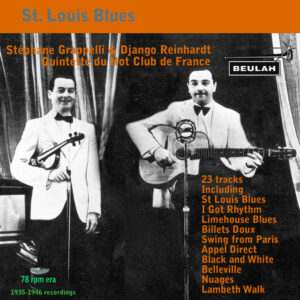

Along with Stéphane Grappelli, a French-Italian violinist, Django went on to form one of the most seminal and influential bands in the history of jazz, the Quintette du Hot Club de France. Grappelli had also benefited from a colorful and challenging childhood; he lived in a French orphanage during the First World War and compared his early life to a Dickens novel.

Both Grappelli and Reinhardt were the featured soloists on the Quintette du Hot Club records my father played for me. With his slicked-back dark hair, pencil mustache, and sly smile, Django looked like an earthy 1930s matinée idol. Grappelli had an aesthete’s face with aquiline features—he resembled the classical violinist Yehudi Menuhi, with whom he later played both jazz and classical duets.

Django died in 1953, at 43, of a cerebral hemorrhage, long before my father got a chance to take me to see him. But Stéphane Grappelli lived on into the 1990s, and, sure enough, when he came to London, my father took me to see him play at Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club in Soho, in 1973.

“Stéphane Grappelli,” my father said, grinning and shaking his head, and looking at me, knowing that it didn’t mean much to me then. “One day you can say you saw him play.”

My father died young, too. Not as young as Django, but just before his 61st birthday, of metastasized prostate cancer. Long ago now. My brother and sister and I inherited all his records. All those familiar old album covers that sat on the shelf by the record player while he played, that still make me think of my father, see his closed eyes, mouth quivering as I hear him playing.

The records are in storage. I no longer own a record player. But what a gift he gave me. I listen mostly to classical music and jazz now—Benny Goodman, Louis Armstrong, Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli—all the greats my father played with.

I wish so much I could tell my father how much I love his music. How much it means to me to have gone to those concerts with him to see Benny Goodman and Stéphane Grappelli play. How well and often I remember him playing his clarinet after a long day at work.

Obviously, I can’t do that. But there is a place I go where they still play his music. I discovered it when I first went to the flea market at Cligancourt, St. Ouen, in the north of Paris. There, on the rue des Rosiers, is a time-warp hole-in-the-wall not far from the spot where Django’s caravan burned on the night of October 26, 1928. A neon guitar hangs on the wall above the sidewalk. La Chope des Puces (chope is a beer mug) is a tiny bar-restaurant, unchanged since I first started going there decades ago. On weekends, Manouche jazz-playing guitarists sit on chairs in a tight corner between the zinc bar and the front window. Usually two guitarists at a time, one playing lead, the other pounding out la pompe, the characteristic thumping back-up rhythm; sometimes they are joined by a violinist or a saxophonist

The place is usually jammed. Patrons–locals and tourists—crowd around the bar, sit at small tables. The food, salades, bistrôt dishes, charcuterie, is all good, but the music… it’s the real stuff.

I know.

My father would have loved it.

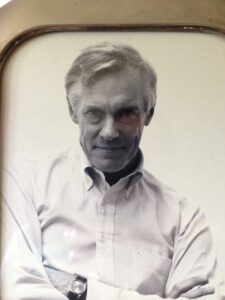

Photos, top to bottom: Django Reinhardt in 1946, the author’s father as a boy in the 1930s, the author’s father in Don Draper years, 1970s, Reinhardt with Ellington c 1946 in New York, plaque commemorating Reinhardt at Samois-sur-Seine, the author’s father playing clarinet as an older man, a video of La Chope des Puces.

Peter Nichols is the author of 6 books of fiction and nonfiction, including the bestsellers, The Rocks and A Voyage for Madmen. He is a regular writer for Frenchly. He lives in Maine.