When we meet Clarisse (Vicky Krieps) in Hold Me Tight, Matthieu Amalric’s delirious fever-dream of a film, she is turning over Polaroid pictures, trying to find matching pairs, as if playing a children’s memory game. “On recommence,” she says. “We start again.” She grows increasingly flustered and angry as she shovels the photos with her hands, repeating the words, “On recommence. On recommence,” her snarled breaths punctuated by the sound of her hands scooping up the blurred images of furniture, faces, a family, and violently slapping them down. Light breaks through a window, giving the isolated moment a hazy glow. The scene exists outside of time and space. We don’t know what we’re seeing or what it means, a sensation that endures through much of the film. The title, “Serre Moi Fort” appears, a flare of sunlight playing on the screen behind them. Hold Me Tight.

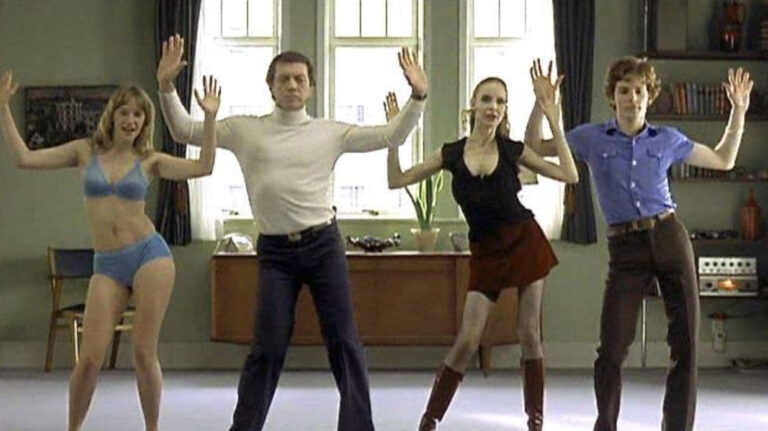

Then she’s alone in a nighttime living room. She creeps through the house, into a bedroom where a man sleeps, in separate rooms two children, a girl and a boy. She dresses hastily, grabs a few things, her purse, a lighter, the key to the vintage Pacer sitting covered in the garage. We move between scenes of her stealing away in the night and her family having breakfast, making each other laugh, wondering why mom isn’t around. Her daughter, Lucie (Anne-Sophie Bowen-Chatet) struggles through the opening bars of Für Elise on the piano. It’s a normal morning, except Maman is gone. As Clarisse drives away, we still hear her family’s voices, Lucie still practicing piano. Her family argues about who knows what about her disappearance. Her husband (Arieh Worthalter) can’t find his lighter. When Lucie plays more proficiently than before, we hear Clarisse’s voice: “Tu sais jouer! I knew you knew how to play!” She blasts music in the car, sings along, poetic match cuts volleying fluidly between her journey and the family she’s left behind, the two realities lyrically echoing one another.

At this point, here’s what we think we know: A woman has abandoned her family, leaving them behind to sort out why she would do such a thing. But the narrative shifts. In a bar, Clarisse gets drunk and imagines aloud how they are dealing with her absence, wraps her arms around a stranger seated next to her, visibly distraught. At home, her words are echoed in the ones her husband says to their children, her voice filling his head, as if she’s telling him what to say. Is she imagining their life without her? In a visceral scene, her husband hurls her things onto the floor. Her son (Sacha Ardilly) rages in her defense: “You threw mom away!” Meanwhile, Clarisse’s behavior becomes erratic. There are memories that confound the viewer. We grasp for clues: Is she losing her mind? As images dart backward into memory and forward into a future that makes no sense, the narrative grows slippery and we reach to figure it out.

Writer/director Matthieu Amalric is best known as an actor, whose remarkable 38-year career includes such cinematic marvels as My Sex Life…or How I Got into an Argument; Late August, Early September; Munich; The Grand Budapest Hotel. He won the 2008 César for his lead performance in Julian Schnabel’s The Diving Bell and the Butterfly and played le commissaire in Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch and James Bond’s nemesis in Quantum of Solace. But Amalric is also an accomplished writer and director, whose feature films include Barbara (2017) and The Blue Room (2014). When a friend handed him an unproduced play called Hold me Tight by Claudine Galea, he wept on a train—and began to imagine its story on screen.

Amalric cast Vicky Krieps (Phantom Thread, Bergman Island) as Clarisse because she appeared to him “like Jeanne d’Arc” as soon as he began to write. Amalric and I met on Zoom to talk about bringing his acting skills into his role as a director, guiding audience reactions, and nuances and themes of the film I can’t include because I don’t want to spoil the experience of watching this unique film. The less you know, the better.

What was your inspiration for this film?

Playwright Claudine Galea wrote the play 17 years ago. My friend gave it to me, and I just cried like a baby, like a child. You don’t know why a nerve is touched. When my producers Yael (Fogiel) and Laetitia (Gonzalez) asked me what I wanted to do next, I said, “I just read this, but I don’t know if there’s cinema in it.” They were moved, too, and I said, “I can try.” The structure was already there in Claudine’s amazing invention of what the character Clarisse is inventing.

So, you were faithful to the play.

There was only one thing I changed. In the play, there was really, really a final twist, almost in the last moment. In the film, it was too much like I was the puppeteer. After the first days of shooting, I discovered that it was Clarisse’s film. She was in control.

For me, it did feel like there was a final twist. There are hints, but it still felt like a sudden revelation or maybe the confirmation of a suggestion. Did you think about the audience reaction?

Yes, we did. Also, we had moments between shooting when we would edit, and that put us in the position of the spectator. I was thinking of people walking in the street after seeing the film, talking and remembering something they had forgotten was there.

Did you decide how to parse out information to the viewer in the editing room?

No, this was written. This was really what attracted me to the movie, to be in her mind and in those chemical reactions that people have in our bodies and minds. I can’t even separate them. The brain is in the belly and that was what made me want to do the film: to be in her delirium.

Are there scenes that are particularly precious to you?

When you shoot, they all are, but one that really says something is the family breakfast scene where they are quite happy. It’s a normal moment. The kids have grown up, and they have forgotten her. They are living very well without her, and she arrives in the head of her husband. She says, “Hey, Marc, I’m here,” and he doesn’t want her anymore. She has to seduce him all over again. Her imagination went too far, with them growing up and the little girl being incredible at piano. Then you see her alone in the kitchen. That moves me.

Can you imagine anyone besides Vicky Krieps playing Clarisse?

After two days of writing, she appeared to me, like Jeanne d’Arc. She just appeared. I saw on the internet that she had a French agent. He said she would be in Paris in three weeks. Oh great, let’s meet. I hadn’t even written a script yet. I just gave her the play and we totally forgot to say, “I’ll tell you if I want to do it.” It was understood. We were like twins. It’s something I’d never experienced before. It’s like we really were brother and sister, something very, very strong. It couldn’t have been anybody else.

How did you work together during the shoot?

It wasn’t through words. I liked to rewrite every morning. Sometimes scenes I’d written a long time ago felt dead, so I’d rewrite to make sure it still worked. I would get on set and I would play Clarisse in the scene we were shooting that day, and then I’d tell Vicky what went through me. For instance, when she was at the café at the beginning, when you think she’s feeling guilt because she left her family, she says, “He doesn’t call me. He’s gonna forget me after a week or a month or a year. They’re all gonna forget me,” and then she grabs a guy and cries. I’d tell her what happened to me when I acted out the scene, how I’d felt, and then we would do only one or two takes and let the camera roll for 25 minutes and create something very, very realistic.

Most people knew you as an actor before you turned to directing. How do these two talents influence each other?

Acting helped me a lot for this film especially, the fact that I could play Clarisse and experiment with the space and energy. I started as a technician when I was 17, and that’s really my life. I love filming music, and I live with a musician, Barbara Hannigan, who’s a soprano and a conductor. I’ve filmed John Zorn for 12 years now. My films wouldn’t be the same if it weren’t for those experiences filming music. I recently did the (Arnaud and Jean-Marie) Larrieu film Tralala and Il sol dell’avvenire with Nanni Moretti, because he’s the guy who made me fall in love with movies in the 80s. He’s also a writer-director-actor, but I’m acting less than I did before.

Does Hold Me Tight offer any hope?

Because of Vicki, yes. That’s why it couldn’t be anyone else but Vicki. She brings this sparkle of light and despair in the same second. This woman has humor and she has her imagination. She loves life. It’s going to be okay.

Hold Me Tight opens in theaters on Friday, September 9.

Andrea Meyer has written creative treatments for commercial directors, a sex & the movies column for IFC, and a horror screenplay for MGM. Her first novel, Room for Love (St. Martin’s Press) is a romantic comedy based on an article she wrote for the New York Post, for which she pretended to look for a roommate as a ploy to meet men. A long-time film and entertainment journalist and former indieWIRE editor, Andrea has interviewed more actors and directors than she can remember. Her articles and essays have appeared in such publications as Elle, Glamour, Variety, Time Out NY, and the Boston Globe.