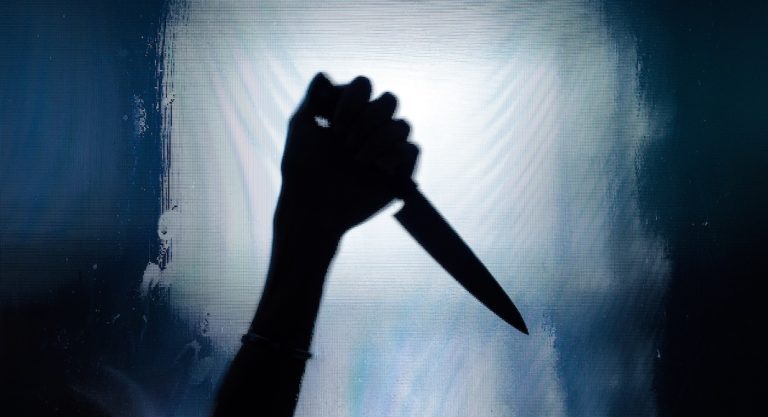

It begins on a cold night in a suburb outside Grenoble at the foot of the French Alps. Clara (Lula Cotton Frapier) has spent the evening at a friend’s house. Buzzing with energy, she announces to her girlfriends that she’s walking home. It’s 3am. The streets are empty. Along the way, a man steps out of the shadows, startling her. She recognizes him beneath the hoodie that hides his face, wonders why he’s there. Then a splash of liquid, a flame, Clara struggling to extinguish the fire engulfing her.

This unnerving true-crime drama, directed by Dominik Moll (Only the Animals, Harry, He’s Here to Help) and co-written with Gilles Marchand, is based on Pauline Guéna’s non-fiction book, 18.3 – Une année à la PJ. The film does a deep-dive into one single case from the intimidating 500-page examination of the police judiciaire (the French equivalent of a police department’s detective bureau) of a teenage girl named Clara whose body was found burned to death.

In the film, which was nominated for 10 César Awards and won six of them, including best picture, two very different investigators team up to take on the case: Johan (Bastien Bouillon), young, serious, and recently named department chief, and seasoned older cop, Marceau (Bouli Lanners), amiable, blustering at times, vulnerable after a recent split from his wife.

Most of us are well-versed in the narrative arc of the police procedural: The cops interview the victim’s friends and family, as well as a string of potential suspects. There are leads and missteps, hope and disappointment, a twist that increases the stakes, possibly putting the investigators themselves at risk, followed by renewed vigor and determination that leads to a showdown between the forces of good and evil. Eventually the perpetrator is vanquished and the world is set right again. Along the way, the characters learn something about the world and the danger and evil which hover insidiously in our midst. Often, they are forever changed.

The Night of the 12th is not that film. While it embraces many of the genre’s conventions, Moll’s dark and harrowing film does not give viewers the satisfaction of following through on the arc it seems to promise. There are many leads, many suspects. Most are scumbags or at least run of the mill jerks. Most were involved sexually with Clara, which is important. Some of the police in the department—like many real people in the real world—think a girl who sleeps around is asking for it. But as deeply as Johan and Marceau long to cuff one of these guys and throw him into a cell to rot for what he’s done, they can’t find sufficient evidence.

“The problem is that any one of them could have done it,” Yohan says at one point. His statement is as much about the case as it is a general insight about the plague of male violence against women that has never been cured. Yohan grows increasingly obsessed with the case, finding release only in his equally obsessive habit of battling his frustrations by riding his bike in endless circles around an outdoor track.

Frenchly editor-in-chief Caitlin Shetterly spoke to Moll and Marchand about their creative partnership; their talented leading man; and making a thriller that unfolds almost like a documentary, with its honest, bracing portrait of regular people struggling to keep living in the face of an evil they cannot understand or control or defeat.

Caitlin Shetterly: You’ve set the film in the French Alps, in Grenoble, but the actual crime it’s based on happened outside Paris.

Dominik Moll: The real crime happened 10 years ago 20-25 miles east of Paris, but it got no media attention at the time. I came across it in the book by Pauline Guéna, a writer who spent a year with the crime squad in Versailles near Paris. The book is similar to Homicide by David Simon, who spent a year with the police force in Baltimore. The last investigation Pauline talks about is the one in the film. What struck me about it and what drew me to it as possible material for a film was that it describes how one of the police investigators gets obsessed with the case, particularly because he wasn’t able to solve it. We’re not the first ones to do this in a film, but the idea is what happens to the case when they are not able to solve it? What are the consequences for them, in terms of frustration, anger, deception? We didn’t want to know more about the real crime than what was in the book. I didn’t want to capitalize on the true crime thing. We treated it as fiction, but unfortunately there was a real victim.

Shetterly: What made you decide to relocate it?

Moll: One of the reasons was that we wanted to treat it as fiction. But the main reason was that Grenoble is surrounded by mountains. Mountains can be beautiful, but there can also be something threatening if you’re there in the dark. The investigators are in that situation, because they are stuck and they turn in circles, as does the character Yohan when he’s on the cycling track. In the city of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne, where the crime takes place, the presence of the mountains is even stronger, because it’s in a deep valley, where that threatening element is quite strong.

Shetterly: What are your cinematic influences?

Gilles Marchand: Dominik and I have known each other for about 30 years, and we have a lot of references in common. We admire Hitchcock, David Lynch. Notably one of the things we talked about for this film was Twin Peaks, the Lynch series, its victim, Laura Palmer, and her presence throughout the film. In The Night of the 12th, the character exists not only as the subject of an investigation, but also as someone whose disappearance has consequences for the people around her.

Moll: In terms of films that we talked about during the writing process, there’s also Jean-Pierre Melville, especially Alain Delon in Le Samourai. He is also someone you know nothing about. You project onto him, which is the case with the character of Yohan, played by Bastien Bouillon.

Shetterly: He’s terrific.

Moll: He’s an actor who has played supporting roles, including in my previous film Only the Animals, where he has a supporting role as an investigator. This was his first major part in a film. He’s been around for a while, but this was a breakthrough role for him.

Shetterly: What point are you making about male violence and misogyny?

Moll: There’s still a big problem in western society with how a woman’s sexuality is perceived. Men having a lot of sexual partners is perceived as positive, but for a woman it is perceived as negative. When you hear that a woman who is a victim of violence, rape, or murder had multiple sexual partners, the idea that she was looking for it and is partly responsible for it comes up pretty quickly. We wanted to question that. But we don’t have an answer. The film is more about asking questions than giving definite answers, but there is obviously a problem with that. There’s a problem with [a woman’s sexuality] triggering violent behavior in men. We also wanted to question how men who aren’t necessarily violent perceive the violence of other men. I don’t think we would have made the same film five years ago. The #MeToo movement was important for us, to become aware of certain things and question certain things and to really listen. We wanted to try to listen. The film is about someone, Yohan, who tries to listen. It allows him to question himself and evolve.

Marchand: Films noirs tell stories about the murders of women. Dominik and I found ourselves in the same situation as our two investigators. We were worried about our own masculinity and our responsibility to tell a story about violence against women, and we tried to imbue our characters with our own concerns about telling this story. It’s a movie that’s told from the point of view of men, but men who are confronted with the violence of others and who are trying to be good people, even in the context of being part of a team of law enforcement officers.

Shetterly: When Marceau attacks a suspect in his apartment, on the one hand you want him to do that and on the other hand, it’s just more male violence. Male violence begets more male violence. It’s a loop that leaves you with more questions than solutions. A typical murder mystery would allow Marceau to beat the shit out of that guy and get away with it, at least morally, but you left us with the question, “How is this going to help?”

You’ve worked together on other projects.

Moll: We met in film school in Paris in the 80s, and since then we’ve written most of the screenplays of my films and the screenplay of Gilles’ film, because he’s also a director. Two directors working together on their respective screenplays is quite unique. I don’t think there’s another example. It’s valuable when we work together, because we both see the story through the eyes of a director and recognize those scenes that are interesting not only to write, but also to put on the screen and direct.

Shetterly: It’s a fruitful partnership.

Moll: Yes, you could say that!

The Night of the 12th opens at the Quad Cinema in New York on May 19, followed by a national rollout.

Andrea Meyer has written creative treatments for commercial directors, a sex & the movies column for IFC, and a horror screenplay for MGM. Her first novel, Room for Love (St. Martin’s Press) is a romantic comedy based on an article she wrote for the New York Post, for which she pretended to look for a roommate as a ploy to meet men. A long-time film and entertainment journalist and former indieWIRE editor, Andrea has interviewed more actors and directors than she can remember. Her articles and essays have appeared in such publications as Elle, Glamour, Variety, Time Out NY, and the Boston Globe.