Fans of Wes Anderson know by this point that the director, whose cinematic style has practically become a genre of its own, draws on dozens, if not hundreds, of influences when making his films. Fans of The Grand Budapest Hotel are now avid readers of Stefan Zweig; The Royal Tenenbaums stans know The Magnificent Ambersons inside out; and Rushmore nerds might be able to pinpoint the exact shots Anderson allegedly stole from The Graduate.

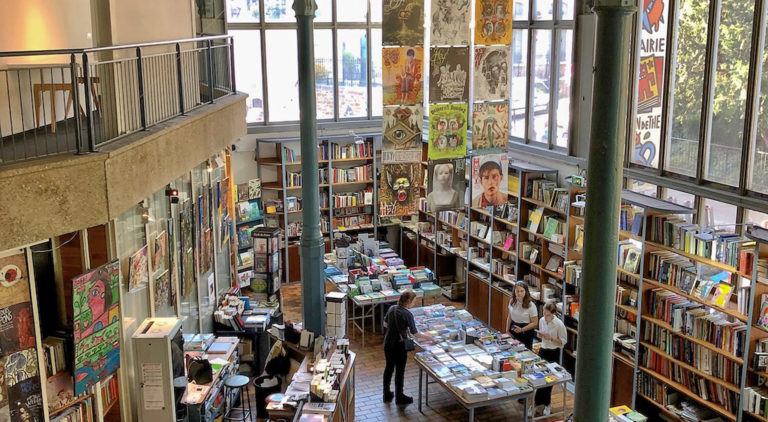

His upcoming film, The French Dispatch, is equally laden with references. Set in a fictional French suburb called Ennui-sur-Blasé, and covering a time period vaguely between 1925 and 1975, The French Dispatch is a vignette-style film centering on reporters for a fictional magazine called The Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun (a not-so-subtle stand-in for The New Yorker). It’s a love letter (though Anderson himself disputes the term) to expatriate journalism, with characters derived from composites of some of the great 20th century writers and editors.

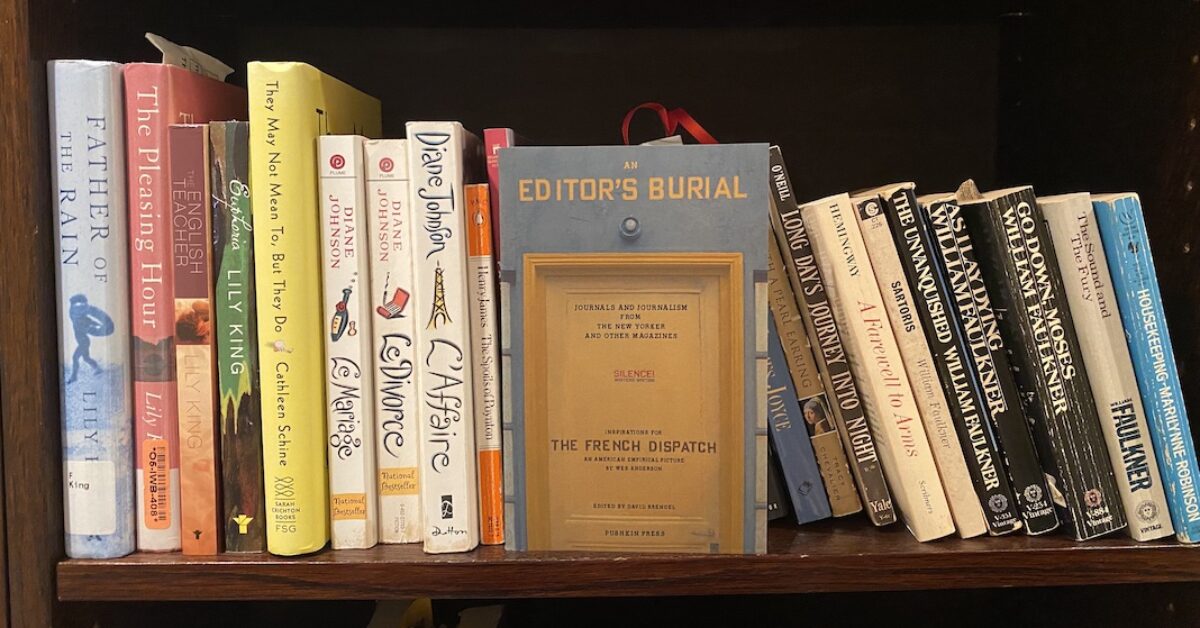

Just a few weeks ahead of the film’s October 22 release, he has published An Editor’s Burial, a collection of essays from The New Yorker that helped inspire the film.

The book opens with a conversation between Wes Anderson and New Yorker editor Susan Morrison, in which Anderson discusses his longtime obsession with the magazine (at one point claiming to own nearly every edition between the 1940s and now). Anderson, who spends much of his time living in Paris, speaks to the joys of expatriation, or “reverse emigration,” as he calls it. “In a foreign country, even just going into a hardware store can be like going to a museum,” he muses. In addition to the great American writers who lived in France, Anderson pays tribute to the great French filmmakers who have influenced his own inimitable style: Godard, Vigo, Truffaut. “France, more or less, is where the cinema starts,” he explains.

The essays themselves begin with tributes to Harold Ross and William Shawn, the two New Yorker editors who inspired Bill Murray’s character in the movie, named Arthur Howitzer. Writers James Thurber, Brendan Gill, and Ved Mehta paint a picture of the magazine’s staff as a manic, degenerate crew, a gaggle of brilliant ne’er-do-wells destined for great heights and greater falls.

Some of the essays feel like peculiar inclusions unless you are familiar with Anderson’s sense of humor, such as a 22-page digression on the habits of New York City rats by Joseph Mitchell. Others feel more on the nose, like A.J. Liebling’s multi-part “Memoirs of a Feeder in France,” or Luc Sante’s thorough history of the evolution of Paris’s suburbs, called “The Other Paris.” An essay by one of the preeminent expat writers of the last century, James Baldwin, is indispensable. Ironically entitled “Equal in Paris,” the essay focuses on eight days Baldwin spent in a Parisian prison for accidentally stealing a hotel’s bedsheets. Trapped in the Paris prison system, he is forced to accept that, whether black, gay, or American, he will receive no separate treatment in the eyes of the law, for better or worse. (In the film, Baldwin inspires Jeffrey Wright’s character, Roebuck Wright.)

The crowning gem of the collection is the 59 pages dedicated to Mavis Gallant’s account of the May 1968 student revolution in Paris. In a cribbed, notational style that manages to convey an incredible spectrum of feelings and observations, Gallant explains how the request by some male university students to have access to the girls’ dormitories in Nanterre turned into the defining social revolution of post-war France. High school students, unions, communists, anarchists, and anyone with a battle to pick went on strike, bringing the economy to a screeching halt and causing French president Charles de Gaulle to flee the country at one point. Though many of the strikers were fighting for unrelated, or even contradictory causes, one message sounded loud and clear: that it was time for France to change.

Mavis’s journal perfectly expresses the peculiar middle distance a foreigner inhabits in times of crisis: just distanced enough to spot the delicious, at other times chilling, ironies. When the banks shut down and Parisians begin hoarding everything from potatoes to gasoline, she mentions a friend’s offhand comment: “She says she dreads a cigarette shortage more than anything.” When a young schoolgirl comes home, crying to her mother that the movement needs the young German students about to be deported, Mavis writes that, “Her mother, who spent the war years in a concentration camp, says nothing.” Caught between past and present, young and old, France and abroad, the expat writer sees it all.

For anyone hoping to truly appreciate The French Dispatch, An Editor’s Burial should be required reading. The collection is more than just a highlight reel of some of the best journalism in recent memory, or something to scratch a francophile’s itch for nerdy nostalgia. Instead, it is yet another of Wes Anderson’s impeccably curated confections, designed to make you laugh, cry, and smile wryly while the whole kit and caboodle of the human experience washes over you.