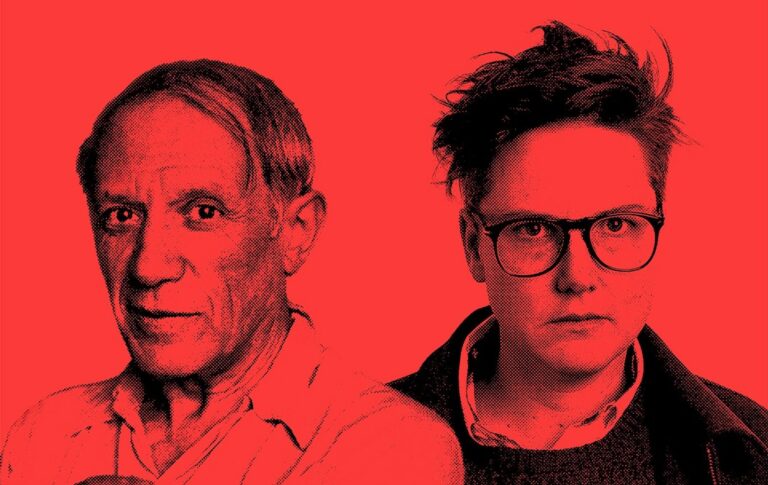

Pablo Picasso is an artist who could be defined as much by his relationships with women as by his works of art. One of the most successful artists of the 20th century, even long after his death (if auction sales are any indication—and they generally are), Picasso’s famous personal life has indeed become part of the public record. With eight museums in Europe dedicated solely to his life and work, one might wonder if it is possible to find any new angle on the man.

Any student of Picasso’s work can recite his paramours: Mary-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot, Jacqueline Roque, just to name a few. But were there any other women who were influential in his life?

Just one. Namely, his daughter, Maya Ruiz-Picasso. A new exhibit at Paris’s Musée Picasso, Maya Ruiz-Picasso, daughter of Pablo, is devoted to the relationship between Picasso and his second child (also frequently referenced as Maya Widmaier-Picasso). The exhibition, which is presented in conjunction with New Masterpieces. La dation Maya Ruiz-Picasso, will run through December 31, 2022.

Maya was the most frequently painted of Picasso’s four children, the daughter of his mistress Mary-Thérèse Walter, with whom he was involved during much of his first marriage to the ballerina, Olga Khokhlova. The museum describes the new exhibition as, “the precious testimony of a relationship between a father and his daughter.” But those willing to peek just below the surface will find some darker insinuations.

The exhibition opens with a film, “Maya dans l’œil de Picasso,” in which Maya’s narration overlays images of family life in Picasso’s various households. It opens with the haunting expression, “I was the manifestation of his sin.” Right there, Maya examines the role her existence played in Picasso’s decision to leave his first wife for his mistress. She goes on to describe how, “women kept coming into his life and into his work,” and gives the frank account of a child accustomed to the shifting loyalties and affections of a capricious man. Not all of her observations are generous, as for Dora Maar, his mistress during his relationship with Mary-Thérèse, whom Maya describes as “the salivating woman.”

Maya talks about Picasso’s love for children, and, in particular, for painting them. Between 1938 and 1939, a one year period, the artist painted his daughter fourteen times, in a singularly impressive series. Though Maya was only three or four years old at the time, her gaze in those portraits reflects a maturity beyond her years, and can be interpreted as something of self-portraiture, or family exhibition at any rate; Picasso imbues the paintings of his daughter with many of his own qualities, as well as with those of Mary-Thérèse. The result is a captivating series of works that uses childishness and precociousness as masks for Picasso’s own private hungers and jokes. And he didn’t stop with just painting his daughter. A large part of the collection is comprised of toys he constructed for Maya, dolls and paper cutouts and puppet theaters, made with simple materials that reflect the wartime scarcity of the era. It shows Picasso in a playful and innovative mode, doodling for his child’s amusement and searching for new ways to delight and entertain her.

However, Maya appears to drop off as subject by the time she hits puberty. She mentions in the film that Picasso later preferred his younger children, Claude and Paloma, as subjects. Those children of his later mistress, Françoise Gilot, were born just as Maya entered her teenage years. Just as Picasso’s lovers were traded in for younger models, once he had chewed them up and spat them back onto the canvas, his eldest daughter appears to have lost her special sparkle by the ripe age of twelve.

Picasso and Maya continued to work together for many years, but cut off contact around the time of Maya’s marriage to Pierre Widmaier in 1960. For the last two decades of his life, the artist and his daughter didn’t speak to one another. The circumstances around this falling out are referenced only vaguely, attributed to Picasso’s disappointment with his daughter’s choice to leave his home and get married.

Despite this apparent falling out, Maya went on to work as an art historian beginning in the 1980s, and has been essential to archiving and preserving not only Picasso’s paintings and artworks, but also his personal effects. Some of them, included in the exhibition, are unsettlingly personal: Picasso’s fingernail clippings, pieces of his hair, and even a painting of his that incorporated his daughter’s feces. Some of the show feels more like the wild fanaticism of a groupie rather than the fond memorial of a loved one.

On the whole, the exhibition appears to reflect Picasso’s tendency to idolize, and later discard, the women in his life, resulting in a desperate plea for his attention that is echoed beyond the pale and throughout generations. The exhibition is co-curated by Diana Widmaier Picasso, Maya’s daughter, also an art historian and Picasso expert. Born in 1974, the year after Picasso’s death, Diana seems, too, to have fallen prey to an obsession with preserving and promoting her grandfather’s life and work.

It feels strange, in a post-#MeToo era, to elevate a man like Picasso for his relationship with his daughter, while the shadows of the women he hurt linger in the background. Françoise Gilot was blacklisted after coming clean about her relationship with the artist in her 1964 memoir. Mary-Thérèse Walter and Jacqueline Roque both committed suicide. And Dora Maar is widely alleged to have been a victim of physical abuse at Picasso’s hands. This is, after all, the man who claimed that, “There are only two types of women: goddesses and doormats.” Bringing Maya Ruiz-Picasso’s relationship into the picture seems calculated to spin the conversation in another direction. But it feels forced. Can one still enjoy the exhibit for the art itself? Of course. But there are conversations yet to be had about how we contextualize it.

Catherine Rickman is a writer and professional francophile who has lived in Paris, New York, and Berlin. She is currently road tripping around Europe, and you can follow her adventures on Instagram @catrickman.