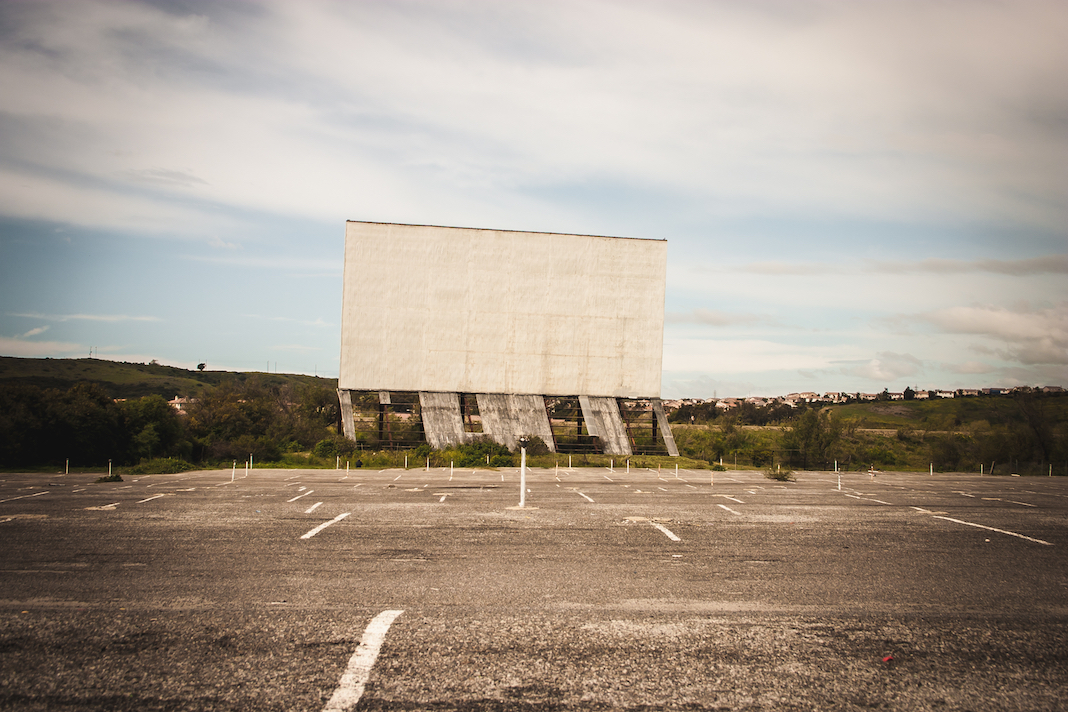

While waiting for the theatres to reopen, projections for spectators in cars are multiplying. The National Federation for French Cinema is complaining to the CNC. By Philippe Guedj and Pascale Hugues

Engines… go! While for the past two months, cinemas have been gathering dust, drive-ins are re-stretching their canvases for vehicle-bound spectators. While waiting for the multiplexes to reopen (in July, French exhibitors hope), this vintage projection mode is taking off again in some countries to remind the public that the experience of the seventh art is still better in front of a big screen, and in public, than at home in front of the TV. In the United States, the cradle of drive-in cinema, Robert De Niro himself has championed the revival of this mythical hobby, in order to compensate for the closure of cinemas since mid-March. In partnership with AT&T and IMAX, the Tribeca Film Festival (of which he is the co-founder) will undertake a travelling event starting June 25: the “Tribeca Drive-In”, which will take over various venues to screen old and new films, concerts, and sporting events. Of the 306 drive-ins still in operation in the United States (compared to 5,000 in its golden age), 50 have remained open, mainly in the Southern and Midwestern states.

The rise of drive-ins, which are rushing to the bedside of the suffering 7th art, can also be observed in Europe. Germany is witnessing a real renaissance of the autokino with, since the beginning of March, 43 radio frequencies allocated to this version of the American drive-in across the Rhine (each spectator receives the sound of the films via his or her car radio by connecting to an ad hoc frequency). And while 80 applications are still being examined, a new autokino (the Cinedrive) opened on April 16 in Mönchengladbach, while the largest of them, based in Essen, dates from 2015 and offers a capacity of 1,000 parking spaces. In Berlin, an autokino is also expected to open in the Neukölln district, in the car park of the Estrel Hotel on the famous Sonnenallee – since the end of April, the place has been used as a drive-in coronavirus testing facility. The sanitary rules are the same everywhere: online-only ticket purchases, a maximum of two people from different households in one car, closed snack bars and no food delivery possible, and you have to bring your own picnic and drinks.

And what about France in all this? Even if drive-ins in France only enjoyed ephemeral and local popularity between the 1960s and 1980s, the dreamlike power of the myth remains. Set up on a whim in less than three weeks and with 35 volunteers by independent distributor Mathieu Robinet (former director-general of Bac Films), the Drive-In Festival intends to rekindle this flame by offering, starting May 16, a tour of screenings across France. The first city to be visited is Bordeaux, where, on the vast Place des Quinconces (Editor’s note: Europe’s largest square in the heart of a city), a film will be screened every evening at 9 p.m. until May 24, in front of an audience of around 300 cars (three people per vehicle maximum). Security measures will, we are told, be scrupulously respected: distribution of free masks on the spot for spectators who do not have them, markings on the floor, 100% online ticketing, scanning of tickets through the window… “Even if people stay in their cars, it will remain a collective experience and, after two months of confinement, I feel how much I miss communing in front of a film. I saw this travelling festival as a way to pave the way for the reopening of theatres and to recreate a desire for cinema,” comments Mathieu Robinet, who had to go full throttle to negotiate (and was still negotiating yesterday) temporary operating visas with the CNC.

As for the Drive-In Festival programme: it will consist mainly of French films (and a few foreign ones), treading the middle ground between auteur cinema and popular fare: Hippocrate (which will get the ball rolling this Saturday evening in Bordeaux), Les Invisibles, Les Combattants, Le Grand Bain, Whiplash, La Tortue rouge, and finally, Tomboy. At Bordeaux’s City Hall, they were jumping at the opportunity of this post-quarantine artistic event: “I thought this idea was magnificent and psychologically very important for the public,” comments Fabien Robert, first deputy in charge of culture. “The operation is non-profit, for a limited time period, the organizer has committed to respecting the barrier gestures and taking measures to offset the carbon cost of the cars [whose engines will have to be turned off at each screening].” But some traditional exhibitors are not very keen on this somewhat alien initiative. Influential cinema owners in the region, such as Michel Friedman (Le Grand Écran cinema in Langon) and Damien Gérard (UGC Ciné Cité Bordeaux), have expressed their regret to the town hall that they were not consulted before the operation. “I had to reassure them about the exceptional and non-competitive aspect of this festival,” says Fabien Robert. Arnaud Vialle, head of the Sarlat Rex (Dordogne), finds the initiative “respectable in theory.” “But I remain circumspect about the technical quality of the experience, will the conditions really be right for great sound and image? As much as I believe in open-air cinema, where you can drink a beer, lie down, enjoy the film with a real feeling of true freedom. But confined to a car, I doubt it…”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CAN8AnuHO_R/

At the national level, the National Federation for French Cinema (FNCF) is banging its fists on the table. Today, the organization sent the CNC a vehement message about recent and upcoming drive-in and traditional outdoor screenings. In this letter, the federation states that it “regrets that today’s discussion is taking place without knowing the conditions for the resumption of activity in the medium term, and the immediate financial support that the State intends to provide for the reopening of movie theaters, and for film distributors, in the first months of the resumption of activity.” With regard specifically to drive-ins, the FNCF calls for “extremely strict application of the regulatory system in force […] There is no reason why these initiatives should escape the general rule and endanger spectators and employees.” The FNCF, which also demands “a very strict application of the authorization procedure,” also says that it “deeply regrets the media and economic damage that will be caused by these demonstrations, which divert spectators, the media and the local and national administration from the only fight to be fought: the reopening of cinemas, the only place that structures and perpetuates film culture.” Not exactly a love story…

The drive-in, a return to a safe haven in times of crisis

As for Mathieu Robinet, he makes sure to make a show of waving the white flag: “I am not at all the messiah and saviour of movie theaters, we just want to help bring some enchantment to this very gloomy period. The Drive-In Festival is a non-profit association, there is no way we can compete with movie theaters, which are sacred to me, this festival is a fleeting event that will stop as soon as they reopen. In any case, especially because of the sanitary protocol, a drive-in today is not a profitable exercise, unless you charge exorbitant rates” (those of the Drive-in Festival are 10 euros per adult and 5 euros for minors). And while the festival has undertaken to “give all profits to cinemas and distributors in difficulty,” the details of this process have not yet been communicated, but Fabien Robert assures that “the Bordeaux City Council will ensure that this commitment is respected.” After Bordeaux, the festival will migrate to Marseille, then to the Hauts-de-France and, in addition, at Crest (Drôme), the town hall inaugurated its own drive-in on May 12. And on May 26, Caen (Calvados) will take its turn with a drive-in that will be a collective initiative of local operators.

For film historian Régis Dubois, author of the book Drive-in & Grindhouse Cinema (2017, IMHO), quarantine alone does not explain this cultural resurrection: “The drive-in, born in the 1930s in the United States with the explosion of the automobile industry, really experienced its golden age in the 1950s and 1960s. It took off in America thanks to the baby boomers who saw it as a way to make out and escape parental supervision. Glorified in films such as Grease or American Graffiti, they are definitely linked to the carefree spirit of the Glorious Thirties, and this renewed interest is part of the same fashionable vintage aesthetic, a sign of a return to certain safe values in times of crisis.” As a big fan of the genre, Régis Dubois necessarily welcomes initiatives like the Drive-In Festival: “It’s a very good idea as long as the cinemas don’t reopen, but it remains to be seen whether the magic will work again and the audience will feel confident, just as they once felt safe in a theatre.” Since the opening of the ticket office on May 13, more than 450 tickets have been sold for this past weekend and, for the first screening on Saturday night (Hippocrates), several local and Parisian media teams will make the trip. So it probably won’t be the final act of the drive-in in France… Unless the FNCF, which hasn’t answered our calls, rolls the end credits on this adventure.

This article was first published on Le Point and is published here in partnership.