There are few Francophile Americans – you could probably fit them on a bus – who know exactly what they’re celebrating on “Bastille Day.”

First of all, it’s not “Bastille Day.” Imagine if a foreign nation insisted on calling the 4th of July by some other name – and the whole world followed along? The French refer to their national holiday as the 14th of July (quatorze juillet) or simply the National Celebration (fête nationale).

Doesn’t it commemorate the taking of the Bastille on July 14th, 1789? Yes and no. You can safely say that, above all, the quatorze juillet celebrates the abolition of absolute monarchy.

But the 14th of July is a two-headed holiday like none other. A 19th-century compromise between ex-monarchists and Jacobins, the law creating it is intentionally vague, honoring either the revolutionary violence of Bastille or the peaceful and all-but-forgotten Fête de la Fédération. Or both.

July 4th, by contrast, is a straightforward commemoration of the signing of the Declaration of Independence of the United States of America. There is no ambiguity, no two sides to anything.

Just imagine if July 4th celebrated a happening at which King George reached out to victims of the Boston Massacre? If it memorialized both American Independence and the democratic union of the American Colonies and Great Britain under a constitutional monarch?

The 14th of July commemorates such a love fest: the Fête de la Fédération, which took place on the 14th of July in 1790! The French celebrated it all over France but most spectacularly in Paris on the Champs de Mars when Louis XVI took center stage along with the members of the National Constituent Assembly. The Marquis de Lafayette led an oath – and the king later joined in – to uphold the laws of the National Assembly.

Marie-Antoinette then held the royal baby aloft to the deafening applause of almost half a million spectators. From the top of a triumphal arch Thomas Paine unfurled the Stars and Stripes, the first time the flag ever flew outside of the United States.

By 1790, the French had accomplished the most revolutionary act in European history – ending the divine right of kings – not without bloodshed but without a bloodbath. That was to come later. France was living under a constitutional monarchy – though the Constitution wasn’t quite finished, its principles were firmly established. The French had a king swearing allegiance to the laws of the people’s representatives.

The Fête de la Fédération is French history’s Path Not Taken. By the following year, the Revolution resumed its descent towards the violent chaos of the Reign of Terror.

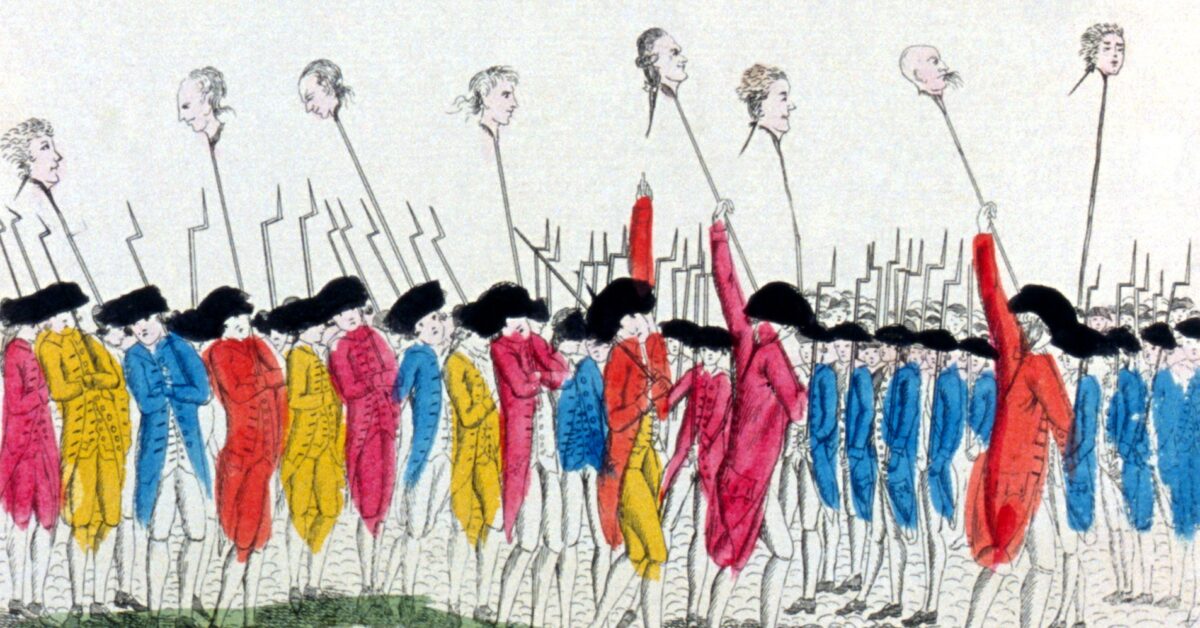

Today, Bastille Day symbolizes the relationship between blood and freedom. But the fall of the royal fortress-prison was less than glorious. After its surrender, a mob tortured the fortress governor to death, hacked his head off and created a revolutionary tradition – parading a severed head on a pike.

Before Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette were beheaded in 1793. Before the Revolution devoured its children during the Reign of Terror and before Napoleonic wars convulsed Europe, there was the hallucinatory, peaceful patriotic fête. The senator who put the creation of the 14th of July holiday to a vote in 1880, Henri Martin, called the Fête de la Fédération “the most beautiful day in French history, perhaps in all of history.”

And, as Martin pointed out, “not a drop of blood was spilled.”