I discovered Jules Verne when I was home sick from school, aged 10 or 11. Must have been more than a cold because I was in boarding school at the time, so whatever ailed me—I remember a Scarlet Fever outbreak—sent me home.

My family had moved to London from Connecticut in 1959. We’d sailed across the Atlantic on the Cunard liner Caronia: six days aboard a throbbing, elegant vessel from an already vanishing epoch, with a movie theater, swimming pool, vaulted dining rooms, frescoed walls, deck chairs from which to view the passing, limitless ocean. We’d packed steamer trunks. One dressed (insofar as was possible) for dinner.

I didn’t realize then that my parents were bold and brave adventurers. My father had become bored commuting by train into New York, being the man in the grey flannel suit. My mother was a painter who loved the Impressionists. In Riverside, CT, they got to know another American family that briefly lived across the street. That family had lived in Paris and they were going back in a year. They were as funny and sophisticated as a Billy Wilder movie, the kids spoke French, they vacationed on the Mediterranean. My parents listened to them, looked at their kids, and thought, We want that. So they moved to England (with three young kids, the language would be easier). They did it without the internet or Lonely Planet guidebooks; my father didn’t have a job (but he had a idea for a one-man advertising business that worked out very well). They simply sold everything, picked up and went. As a result, I grew up in England and came to know Europe the way I might have known Cape Cod if we’d remained in Connecticut. I spent summers on the Spanish island of Mallorca, I skied in Austria and Switzerland. I had French and Spanish friends and soon spoke both languages. I found I liked geography and history at school. What my parents had given us, their children, was a gift I wasn’t aware of until well into adulthood.

My parents’ wanderlust and embrace of adventure was evident in the shelves near my sickbed, where I found a book entitled: Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. I opened it and the first words arose like a charm: “The year 1866 was signaled by a remarkable incident, a mysterious and puzzling phenomenon … rumours which agitated the maritime population …”

When I finished a day or so later, I discovered—I remember the shelf, the book, the moment of unexpected joy, the gift to continue a journey—another book by the same author: Around the World in Eighty Days. And then another: Journey to the Center of the Earth! There were other books on that shelf—The Gauntlet by Ronald Welch, Swallows and Amazons by Arthur Ransome—but I remember best, and took in most deeply, the Jules Verne books.

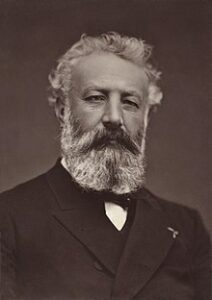

Jules Verne is the most widely translated author in the world, after Shakespeare and Agatha Christie. This has enhanced and harmed his literary reputation. Today, his stories, his settings, his fantastic inventions, can seem quaint or nostalgic, like an old steam engine with interiors furnished by the Paris flea markets. But in his day, Verne was at the cutting edge of modernism. He was writing speculative fiction about technology— submarines, air travel—that was unfolding as he wrote. He was the William Gibson (Neuromancer) of his time. He wrote 54 “Voyages Extraordinaires.”

In France, where he influenced the literary avant-garde, Verne was considered an important author. But in the English-speaking world, “Jules Verne” became a notion of genre fiction for children’s books, a franchise for translators who abridged, altered, even invented parts of his works. In my sick bed, I surely read abridged or Bowdlerized editions for young readers. With them, I recovered from whatever sent me home–but I was left with an incurable travel fever.

Fifteen years later, when I was in my mid-twenties, I was living aboard a small wooden sailboat, without an engine or electricity, in the Caribbean. It was a lifestyle that enabled me to have a home and at the same time go anywhere. The boat was built in England in 1939, in a traditional, even old-fashioned design, and its interior would not have been out of place in a Jules Verne novel: Wood beams, a kerosene lamp, shelves full of books.

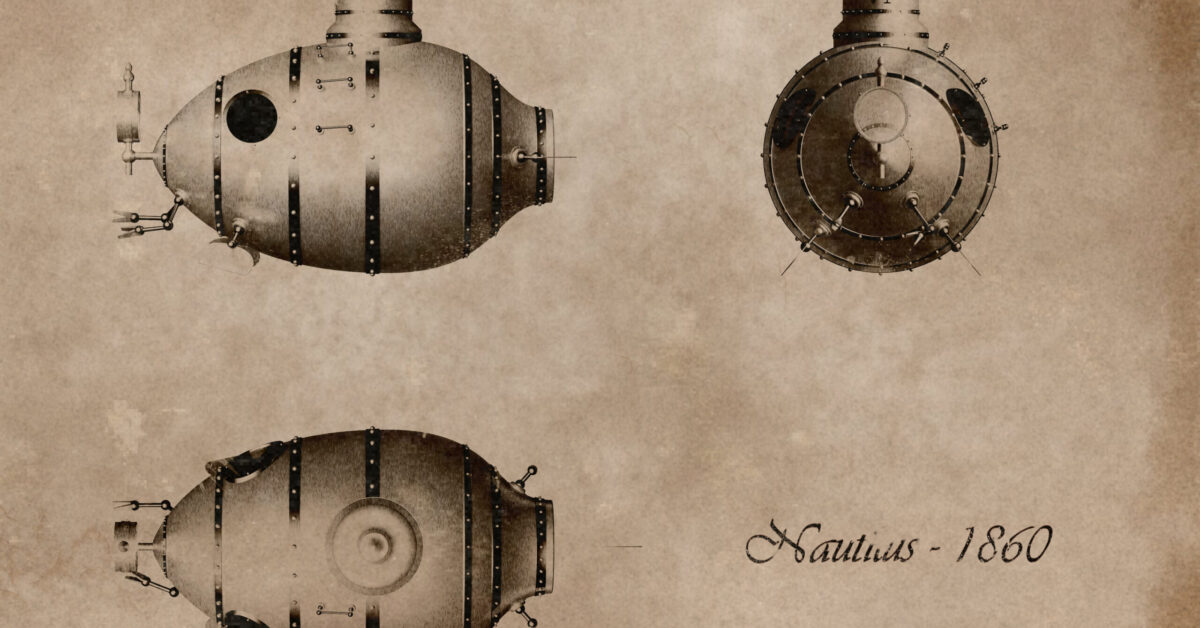

This was also the pre-GPS age. To find my way across the unmarked sea, I learned celestial navigation: measuring the angles between the sun and the stars and the ocean horizon with a sextant; a mechanical contraption with calibrated knobs, mirrors, made of heavy brass, in a beautiful wooden box. One of the illustrations in my old 20,000 Leagues book showed Captain Nemo standing on the deck of the surfaced Nautilus, sextant raised to his eye—in Verne’s day it was still the only way to navigate at sea.

I sailed across the Atlantic three times using this device. Traveling at 4-5 knots across the featureless ocean, navigating with the techniques of Captains Nemo, Cook, and the mariners of yore, it felt like time travel back to a more adventurous age.

“A whaleship was my Yale college and my Harvard,” Herman Melville writes in Moby-Dick. In six years of full time cruising in my little retro time capsule, I read a library’s worth of nonfiction adventure, most of it set in the 19th and early 20th centuries: Joshua Slocum’s Sailing Alone Around the World, the first and still the best written account of a solo circumnavigation of the world (I have a first edition); Fridtjof Nansen’s Farthest North, the account of his journey across the arctic in an early attempt to reach the North Pole; Shackleton’s voyage aboard the Endurance; the race between the epic bungler hero Englishman, Robert Scott, and the perfectly prepared and experienced Norwegian Roald Amundsen to the South Pole—Amundsen beat Scott by a month and Scott and his party all died on the way back. These true-life, Verne-ish stories, read while crossing oceans in my own leaky little vessel were my education.

Verne himself was not much of a traveler. He, too, went to boarding school, in Nantes, near the family home; his teacher, Madame Sambin, was the widow of a naval captain who had disappeared at sea. She told the students that her husband was a shipwrecked castaway and would someday return. The Verne family home, on the banks of the Loire, offered the young Jules a constant view of passing ships. His uncle was a shipowner who had sailed around the world. But none of these associations kindled a traveling itch in the boy. His own childhood literary influences were the sweeping, romantic works of Victor Hugo. Writing was not approved by Verne père, who insisted that his son go to law school. Though he got his degree, and his father begged him to begin practicing law, Verne refused. He’d already begun writing stories, acquired a passion for science and geography, and told his father that he was sure he would find success as a writer.

As a child, I was impressed by the Mike Todd–produced film, Around the World in Eighty Days. David Niven was a suitable Phileas Fogg for Hollywood. One really did go around the world for the film’s locations: in a balloon over the alps, to a bullfight in Spain, to Japan and the wild west. The cheesy 1959 movie Journey to the Center of the Earth, with Pat Boone and a runaway goose in a papier-mâché studio underworld, was less fun.

This winter, coinciding with Verne’s 194th birthday, Masterpiece, on PBS, began streaming the 8-part, multi-national production of Around the World in 80 Days. Here, finally, is the authentic look of Jules Verne’s world—or the way I imagine it looked: The old fogeys in the Reform Club; the London, Paris, Arabia, and India of 1872; the ships, the casbahs, a beautifully CGI-generated Hong Kong.

And David Tennant (Broadchurch, Dr. Who) is a perfect Fogg. Part prig, part Indiana Jones. He is rubber-faced, by turns gloomy, outraged, deliriously enthusiastic, and athletically committed to his mission. Less effete than Niven, who traveled around the world rather like Prince Charles, tugging at his shirt cuffs, looking around from a lofty height of privilege, Tennant strides through railway carriages, across sand dunes, pilots that balloon (not in Verne’s story, though he did write a novel Five Weeks in a Balloon, 1863) with that mix of uptight buffoonery and heroic persistence that did, in fact, take British gentlemen explorers to the ends of the Earth to map out and found an Empire. Not a caricature throwback; you can see his ilk today in Parliament heckling Boris Johnson over Partygate.

In this glorious new adaptation, the novel’s Detective Fix who follows Fogg around the globe suspecting he is a criminal, is now a very modern young lady, the Titian-haired (a wig) Abigail Fix, a dogged reporter for the London Daily Telegraph, who reports back to the newspaper on Fogg’s progress. Miss Fix is charmingly, breathlessly inhabited by the German actress Leonie Benesch, who also does a nice turn as a fascist’s unwitting assassin in the stylish German series Babylon Berlin. The smoldering, limpid-eyed French actor, Ibrahim Koma, is a great improvement on the Chaplinesque Cantinflas as Passepartout. This version of Fogg’s wily servant is flawed, sympathetic, and develops a reciprocated love interest in Miss Fix. And, not least, Masterpiece’s Around the World brings a sumptuous level of art direction to viewers who have missed the production values of Downton Abbey.

Eventually my boat—which, like all floating vessels, exhibited an unrelenting desire to sink—sank. I didn’t return to the sea full time. Once ashore, I began to write full time. First, screenplays that went nowhere, before I turned finally to what I knew: books. My first book was a memoir of my sailing years, the sinking of my boat (and also the sinking of my first marriage.)

I followed that with historical nonfiction about the first singlehanded nonstop round-the-world yacht race; the voyage of the Beagle and its fanatic Christian captain, Robert FitzRoy; disaster among the Yankee whaling fleet; then a novel about a ship of fools in the Arctic. And more.

In the end, writing became for me, as it did for Jules Verne, the greatest adventure of my life. It still is.

Peter Nichols is the author of 6 books of fiction and nonfiction, including the bestsellers, The Rocks and A Voyage for Madmen. He lives in Maine.