“The Zurbaran, where is the Zurbaran? “On June 3, 2016, the staff of the Musée Girodet de Montargis, in a state of shock, finally entered the reserves where almost all of its 5,000 works of art were stored while the museum was under construction. For the previous three days, sculptures, plasters, bronzes, prints, pastels, canvases — some of them of great value — had been underwater. Throughout the geological region of the Parisian Basin, the Seine flooded and rose relatively quickly, but upstream of Montargis, a 17th-century canal suddenly gave way and a tsunami of water submerged the stocks of the fine arts museum. Some works were destroyed, others rendered unrecognizable. A painting by Géricault was covered with silt. The spectacular “Saint Jerome Penitent” — almost 2 meters high, designed by the Spanish painter Zurbaran — was swept away by the powerful wave and lay at the bottom of the reserves: it was moldy, its colors had begun to change, and the spectacle of this washed-out masterpiece was enough to bring you to tears. “Once the pumping of the water was finally completed, we knew we would only have two days, before the molds settled, to save what we could,” says Sidonie Lemeux-Fraitot, collections manager. More than fifty art restorers from all over Ile-de-France converged on the scene, helping to lay protective canvases, clean the silt, and form a human chain to bring up the bronzes and streaming frames. “Thanks to them, we were able to save 15% of the collection,” says Lemeux-Fraitot. “If we had had to wait for the department’s order confirmations to pay for restorers, we would never have made it, so they all volunteered, putting these invaluable works before their own salaries.”

April 15, 7:40 p.m.: Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral is devoured by flames. Thinking of the incredible value of some 2,000 works of art housed in the cathedral, a man runs, gripped by fear, to Ile de la Cité. Laurent Prades, property manager of Notre-Dame, had himself inventoried and described, in five thick volumes, all these paintings, statues, relics and sacred works. It’s a titanic project to which he devoted six long years. Prades had also helped to establish the essential recovery plan, a kind of roadmap for firefighters that indicates in the event of a disaster what are the works of a museum, library or historical monument to try to save as a priority, and how to access them quickly. On the list for saving in Notre-Dame Cathedral are the precise locations of twelve major works, the “quintessence” of the treasure, in short, but above all the instructions for removing the paintings, opening the windows, and turning off the alarms.

Risk management. Looking at the thick plume of smoke rising in the sky of the capital, crossing the roadblocks that still separated him from Notre-Dame one by one, Prades, running out of breath, did not know if the fire was already progressing inside the building. “When I arrived, the spire had just fallen, but the firefighters, with the recovery plan in hand, were already starting to evacuate the priority works,” he says. “So everything had worked.” The fire was contained well before reaching the wonders of the cathedral, which are now protected in the Louvre’s reserves, but the idea that the crown of thorns or the very beautiful “Nativity” by Le Nain brothers could have disappeared into the blaze was a shock. The plan to save the works of Notre-Dame had only been completed a few months before the fire.

“France is a country with an incredible wealth of heritage, but unfortunately it has no culture of risk management at all,” says Jocelyne Deschaux, President of the Comité français du Bouclier bleu, an international organization that fights for the protection of cultural heritage in the event of conflict, disaster or natural disaster. “We are much less advanced in this field than the Anglosaxons. Despite repeated directives from the Ministry of Culture, Not 10% of our museums and historic monuments have a preservation plan. As for the cathedrals with plans, I think they can be counted with one hand.” Though it is possible, after a fire or flood, to restore or even rebuild damaged monuments, a painting, rare edition, or period cloth that has been harmed cannot be recreated. The destruction of a major heritage is, as we know, a wound from which a nation struggles to recover. “We no longer have a past, no history,” lamented a researcher at the National Museum of Brazil in Rio, whose entire collection went up in smoke on September 2, 2018: hundreds of thousands of archaeological and paleontological finds — including the oldest human fossil in the Americas — and unique remains of pre-Columbian civilizations reduced to ashes in one night.

“In terms of heritage destruction, the 2002 floods in the Czech Republic, which affected dozens of libraries and destroyed hundreds of thousands of precious archives and books, had a profound impact on all European curators,” comments Céline Allain, emergency plan coordinator at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF). Back in 1996, the fire at Crédit Lyonnais, which took place a few meters from the BNF’s Richelieu site, caused the Ministry of Culture to shudder. Since Napoleon III, the library, whose collections are unlike any other in the world, has had its own dedicated fire brigade. But if the fire hadn’t been contained, what should’ve been saved as a priority from disaster? “It was a big realization,” says Allain. “And today, we’re not leaving anything up to chance.” At the four BNF sites, which contain true treasures — ancient papyrus, medieval bibles, cabinets of medallions — the recovery plans are scrupulously kept up to date, renewed for each exhibition and stored in secure cabinets. “We know at all times what needs to be urgently taken out of each building and how to access it.” At the Arsenal location, situated in an area prone to flooding, an archive consolidation system has been set up to quickly evacuate the collections to the upper floors, and the process is regularly tested. “During the 2016 flood, although no water was found in the basements, we took the opportunity to practice and get everything up,” says Allain. “It was exhausting, but we are ready.”

Flood of the Seine. In June 2016, the Seine reached its highest level — 6.10 meters — in thirty years, forcing the Musée d’Orsay, the Musée du Louvre and the Centre de recherche et de restauration des musées de France (C2 RMF), all three of which border the river, along with several other museums, to initiate their flood risk prevention plans and to move up part of their underground reserves to the upper floors. At the Louvre, the task is colossal: 152,000 works, exhibited on the ground floor or preserved in the lower levels, are located in flood-risk areas. At the time, for this type of emergency, we were still far from having completed preparations for the fabrics, carpets, Greek vases, treasures from Eastern, Egyptian, Etruscan and Roman antiquities that the reserves contain in large amounts. The results were alarming: between Thursday evening and Saturday morning, despite the mobilization of the museum’s staff and the fire brigade, only 35,000 works, or barely 35% of the collections located in flood-risk areas, were protected from water after enormous efforts were made. The impossibility of evacuating the basement and the ground floor at the same time was realized. When the Seine finally began to recede, the museum’s management breathed a deep sigh of relief. “If there had been a real 100-year flood — over 8.60 meters — it would have been terrible,” says Mylène Florentin, consultant in preventive conservation. Especially since, as all hydrologists predict, the next 100-year flood will be much larger than that of 1910.

To avoid the tragedy that everyone fears, the museum’s management will inaugurate a huge conservation center located in Liévin, near the Louvre-Lens, in October and proceed for twenty-eight months with the pharaonic transfer of 250,000 works. But this reasonable move and, in particular, the location chosen are far from unanimously accepted. “An hour from Paris, it’s absurd,” laments art historian Didier Rykner, director of the site La tribune de l’art. “How will the conservators, the researchers who are constantly working on the reserves, do their work? Couldn’t you find anything closer?” A criticism to which the President of the Louvre, Jean-Luc Martinez, has already replied: “Liévin meets the standards and addresses the logistical problems. The conservators can take the train.” Rykner is also quick to denounce the risks incurred by a French heritage that he considers poorly protected. During the torrential rains that fell on Paris in July 2017, he was particularly moved by the flooding that had been observed in the Louvre, damaging two of Nicolas Poussin’s “Quatre saisons” and a work by Jean-François de Troy, “Le triomphe de Mardochée,” as the museum had officially confirmed. Moreover, that same summer, lightning struck the reserve of the small museum of Tahitou, in Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue (Manche), destroying 182 paintings, three of which were on loan from the Louvre. The question becomes, can we protect ourselves from everything?

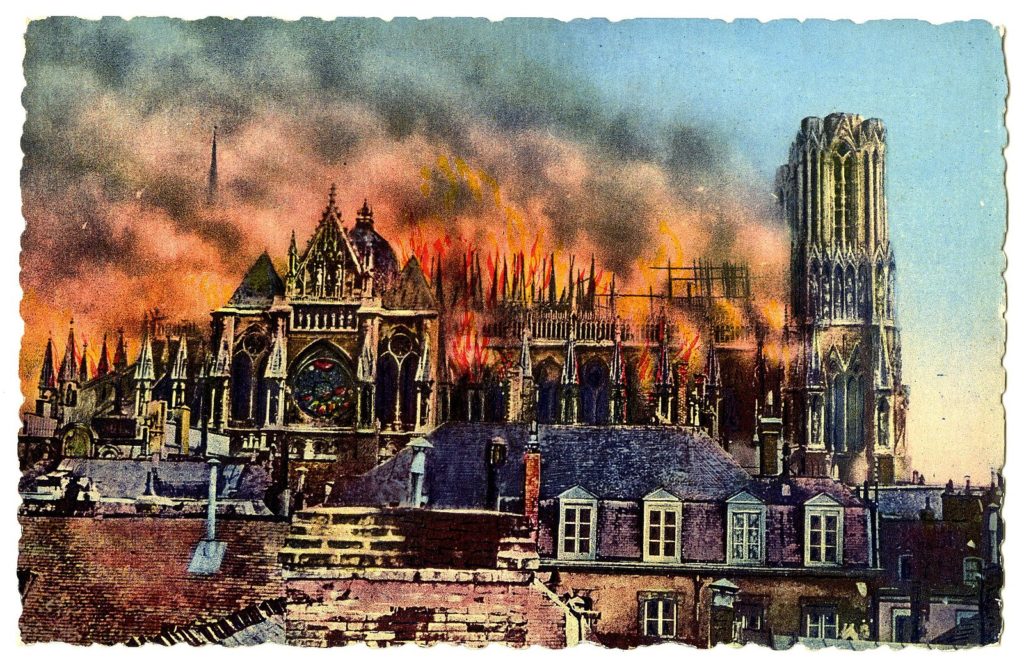

Backup plans. “France has really become aware of the absolute need to defend its heritage, particularly its furniture, after the fire at Reims Cathedral in 1914, which had a major impact on people,” explains Judith Kagan, head of the office for the conservation of the movable and instrumental heritage at the Ministry of Culture. “At the beginning of World War II, for example, many stained-glass windows were stored in large cathedrals and their treasures evacuated to the rear… But the so-called preventive conservation, the presence of firefighters in the Ministry advising us to draw up real battle plans in the event of a flood or fire, all this was not initiated until the late 1990s. The adoption of safeguarding plans in as many historic monuments as possible is crucial, but I recognize that this is not moving fast enough, especially for cathedrals.”

For Mylène Florentin, whose job is to help cultural institutions adopt such emergency plans, the first difficulty is to choose which works should be saved as a priority. “You can’t choose more than a dozen. However, for a curator, choosing only ten works from the hundreds, thousands of works in the museum or monument for which he is responsible is a real heartbreak. To help them, I suggest that they imagine an ideal minimum museum, which they would take to heaven, in short.” Another major difficulty: these plans are real burglary kits for potential thieves. “Where are the most important works, how to unhook them, where are the keys to the windows, how to turn off the alarms: everything is there,” adds Florentin. These plans must therefore be deposited in a secure, fireproof box or in sealed envelopes, but this is not always easy. “Moreover, in a museum like the one on Quai Branly, the platform of the collections, and therefore the location of the works, is constantly changing. “The collection managers have identified five to ten works per sector to be evacuated as a priority, and all museums have their ‘Mona Lisa’ or Rembrandt,” says Eléonore Kissel, head of the museum’s conservation-restoration department. “But above all, it is necessary to train the staff to react, to rely on the savoir-faire of the restorers, to be pragmatic. Do not have a too rigid management of the disaster, because you can never anticipate everything.”

Françoise Leonelli, director of the Musée Jean-Cocteau in Menton, hadn’t imagined that a stormy night, that of October 30, 2018, a 7-meter wave would submerge her beautiful and brand new museum located by the sea, designed by the architect Rudy Ricciotti. A temporary exhibition was held on the ground floor, so the entire permanent collections, including 2,500 drawings, posters, manuscripts, tapestries, prints and lithographs by Jean Cocteau, were being stored in the basement. However, under the weight of the wave, one of the bay windows gave way, and the salt water of the Mediterranean filled the reserves like a jar. Stamps and photographs floated pitifully on the surface. “The 1,000 square meters of basement were under 1.70 meters of seawater,” she says. “We had to call divers.” Then comes the drying, mould and bacteria control: for the past eight months, the museum team, assisted by representatives of the C2 MRF, has been desperately trying to save what it can. “For the pastels, the pigments are very damaged. But the Chinese ink has withstood seawater, it is indestructible,” celebrates Leonelli, adding that the museum was, at the time of the storm, in the process of adopting a safeguarding plan. Knowing the brutality of the incident, would it have been useful to even look at? In the aftermath of the Notre-Dame Cathedral fire, the Bouclier bleu organization asked the management of the Patrimoines de la rue de Valois for official figures on the number of safeguarding plans actually adopted in France. His request, for the moment, has not been answered.

This article was first published on Le Point.

Featured image: Stock Photos from Daisy Chen / Shutterstock